The past is preserved in this Eastern Panhandle village, which celebrates 225 years this year.

Less than two hours from the hustle and bustle of Washington, D.C., is a sleepy town frozen in time. Over the past decade, much of Berkeley County and the Eastern Panhandle has grown with residents and businesses, but in the middle of it all sits Gerrardstown—a National Historic District.

Approximately 90 percent of Gerrardstown’s historic sites still stand, according to Todd Funkhouser, president of the Berkeley County Historical Society. “I call it a sleepy, well-kept secret,” he says of the town, tucked away from the rest of Berkeley County. “It’s a fine example of a present colonial town with most of the original architecture.”

A lifelong Berkeley County resident, Todd appreciates the history, architecture, and culture of Gerrardstown. The community remained relatively untouched even in the late 1800s, after Berkeley and Jefferson counties joined West Virginia and the rest of the Union, when about 500 workers from Baltimore moved into the county to work on the railroad. The orchard industry eventually boomed, and most of that culture remains today. National Fruit, a company whose products include White House applesauce, still harvests in the Gerrardstown orchards, and the neighboring community of Arden also has apple operations.

But perhaps the greatest representation of the town’s history isn’t in stories of its culture and past, but in the buildings that remain. “Our historic Gerrardstown village is a time capsule from days gone by,” says Wendy Hudock, who owns the nationally registered Prospect Hill plantation with her husband, Steve. Prospect Hill was placed on the registry in 1983 when Wendy’s in-laws owned the property. That’s when the old farm was converted into a bed and breakfast, and Wendy and Steve operate it as such today. “Steve and I believe you do not own it—you are a caretaker who passes it along for future generations to share, so that we may keep a tie with our past.”

Beyond the manor’s interior and history, the atmosphere of Prospect Hill also draws people in. “It is a privilege to live in the midst of a part of West Virginia history,” Wendy says. “The Gerrardstown we fell in love with is a bucolic historic village that most folks would be proud to call home. Prospect Hill and Gerrardstown are memorials to the heritage of West Virginia history. Visitors experience peace and comfort with tranquil, pastoral views.”

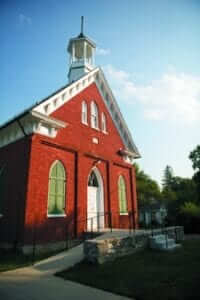

In the early ’70s, the owners before Wendy’s in-laws were in financial straits and sold some of the plantation’s property, says Ruby Sibole. Ruby and her husband, James, bought the land and built the home they still live in today at the base of North Mountain. James has many fond memories of his town, including going to church at Northern Methodist Church before it was torn down and merged with Southern United Methodist in 1942. Southern Methodist sat abandoned for the better part of a century until six years ago, when Northern Virginia resident and architect Kevin Lee Sarring purchased the chapel to restore it. Now known as the Apple Chapel, the project took two years and was finished in 2010. The large brick structure, built in 1883 and listed on the national registry 109 years later, opened up to one large room of pews when services were held there more than 50 years ago, but it was originally a safe haven for Confederate sympathizers after the Civil War.

Community involvement motivated Kevin to open the renovated structure, which he uses as an architect’s studio on weekends, for town events. “I’ve tried to help by bringing artists in,” he says. “It’s just being neighborly.” Beyond hosting art shows, the Apple Chapel also hosted the inaugural event of the town’s anniversary in June 2012.

Reenactors, art, and historical tours will take place as part of the 225th celebration October 6, 2012, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tour stops could include the Hays-Gerrard House, Mill Creek Manor, Oban Hall, and the Gerrardstown Presbyterian Church and church hall. The Hays-Gerrard House was built by John Hays in 1743 and later became home to Reverend David Gerrard, son of John Gerrard, first Baptist minister west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. David laid out the town, originally called Middletown, and named it for his father.

Todd says one of the county’s most beautiful structures is Gerrardstown Presbyterian Church’s hall. “I don’t know any other building in Berkeley County quite like this,” he says, admiring its tin ceilings and unique diamond design of wood paneling, which gives the 100-plus year old building a distinct feel. Genevieve Pitzer, in her 80s, remembers when the church hall was the community center. She used to volunteer at dinners there. “We used to serve the Kiwanis Club once a year. One time we had so many people that we had to get chairs and put plates around on the porch outside,” Genevieve says. She remembers running to neighbors’ homes to borrow dishes—paper plates weren’t around then. “We had a lot of cleaning up to do,” she laughs. “I’ll remember that always.”

It’s memories like this and more to come that give locals that sense of pride and community. “Time has largely untouched the folks of Gerrardstown,” Todd says. “They still live very simple lives.”

WRITTEN BY TRICIA FULKS

PHOTOGRAPHED BY AMBERLEE CHRISTEY PHOTOGRAPHY

Leave a Reply