THERE’S GOLD IN THEM THERE HILLS—Black gold, that is. West Virginia walnut syrup is giving maple a run for its money.

Sponsored By Future Generation University

“It all started at a Friday night social at McDonald’s,” says Gary Mongold, a self-employed mechanic who lives in Petersburg. “There’s a group of us men that get together ever so often to just shoot the breeze. On this particular Friday, my buddy Mark Bowers told us that, if anybody knew of folks with some walnut trees, Future Generations University was looking to experiment with walnut tree tapping—and walnut syrup was selling for around $500 a gallon, as opposed to maple syrup that was selling for only $40 a gallon. You could say that piqued my interest.”

Mongold told his friend that he had a few walnut trees and then sent him some pictures. “By God, when Mark saw my pictures, he flipped out,” he recalls.

Mongold doesn’t just have a few walnut trees; he has around 1,400—12 acres’ worth. Future Generations University (FGU), a global graduate school headquartered in Pendleton County that specializes in applied community development, sent its renowned maple expert, Research Faculty and Maple Commodities Specialist Dr. Mike Rechlin, and Field Coordinator Kate Fotos to check it out. “When I first visited Gary’s property, I was astounded at how many walnut trees he had, and I was excited to see what he could do with it,” Rechlin says. “West Virginia may never rival Vermont when it comes to maple syrup production, but Vermont has about four walnut trees, lacking the resource base to support a walnut syrup industry. Walnut syrup is something West Virginia can lay claim to.”

The global maple syrup market is a $1.5 billion industry that West Virginia is just beginning to tap into. In 2022, West Virginia produced 13,000 gallons of maple syrup in an average of 34 days per farm. Future Generation’s Appalachian Program hopes to help expand West Virginia’s production. “We want to create economic diversification and help landowners utilize their resources in a smart and sustainable way so that they receive a monetary return off their land,” says Luke Taylor-Ide, FGU’s vice president of community engagement.

In fact, West Virginia is thought to have more tappable maple trees than Vermont. “Maple syrup is an already-recognized high-commodity product that is in high demand,” Taylor-Ide says. “But sugar maples aren’t the only trees that can be tapped for syrup. We have been tapping birch in the past and different types of maples, sycamore, and walnut and studying their economic viability.”

Walnut syrup is rich and complex with a nutty undertone and a hint of butterscotch. The syrup, surprisingly, doesn’t have the bitterness or bite that people typically associate with black walnuts. “In taste tests, when walnut goes up against traditional maple syrup, it often wins,” says Taylor-Ide.

Since there are only a few commercial producers of walnut syrup in the world, it is hard to find—and the demand is high. But FGU is researching ways to increase walnut sap production to make it a more profitable enterprise for producers in West Virginia. And at $500 a gallon, it is an easy sell. When the university learned of Mongold’s massive walnut stand and his willingness to invest in the equipment, they jumped at the chance to help him tap his trees and guide him through the process. “Future Generations was wonderful to me. I couldn’t have done it without them,” Mongold says. “I had no idea how to get started and incorporate today’s modern technology. They told me what size of tubing to use, and they measured it all off and gave me the length I needed. They helped lay out the lines, showed me where they needed to go, and helped run the tubing. It was all downhill from there, so to speak. If anyone is interested in getting started in the syrup industry, they need to give them a call.”

In October 2021, Mongold invested around $7,000 in tubing, fittings, and collection tanks and started running lines. “I got a hand-me-down dairy pump from my friend Mark that I reworked and made into a vacuum pump. A new one would have cost me $3,000, but I only spent $100,” he says.

The word got out. Neighbors, friends, family, and friends’ cousins showed up to help him run the lines and then later to tap the trees. “It is unbelievable what he has,” says his friend Mark Bowers, who knows a thing or two about the maple syrup industry. He owns nearby Bowers Maple Farm and taps around 2,200 maple trees and produces nearly 400 gallons of maple syrup a year. “I bet you can’t find another place like it in the state. It is unique—his walnut grove is on a perfect slope and the trees are close together, so he doesn’t have to run an unbelievable amount of piping.”

Tapping walnut trees is a different process than working with maple, which is considered a diffuse-porous hardwood. Walnut is a semi-ring porous species. This affects how deep the tap should be placed and how the sap flows. Walnut yields less sap and has a high pectin count, so it can gum up the reverse osmosis membrane. “Future Generations has been working with Marshall University and West Virginia State University to study methods to remove pectin from the sap to address this issue as well as experimenting with alternative clarification methods for walnut syrup,” Taylor-Ide says.

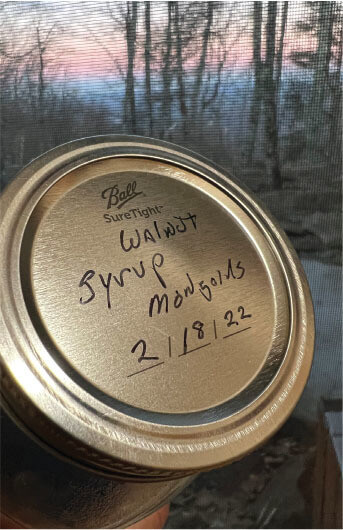

Throughout the season, Mongold collects data for FGU. “We know a lot about maple syrup, but we don’t know much about walnut. It’s all new. We’re learning as we go,” he says. “I keep really good records for them on things like how many gallons of sap did we collect per day? How long did we boil? How much propane did we use? How much more did we pull when we added vacuum?” For his efforts, FGU not only helped him overcome obstacles, but it also designated his 12-by-18-foot sugar shack “FGU’s Mongold Walnut Research Center.”

“The data that Gary provided taught us that it is important not to overdrive the spouts. The familiar hammer bounce and pitch rise on a straight-barreled maple spout sets too deep, so when tapping walnut, we need to choose a spout with as much taper as possible. We are working with Marshall University’s Robert C. Byrd Institute of Advanced Manufacturing to design a spout specific to walnut,” says Rechlin. “We also learned that, with relatively low levels of vacuum, we doubled the sap output.”

In 2022, Mongold bottled 17 gallons of syrup—liquid black gold. “I’m pleased with what we got, but we had a really short season,” he says. “Because it got so warm, I had to throw out about 24 gallons of sap that had soured, but I think, if Mother Nature cooperates, we’ll do even better this year.”

This season, he plans on putting in 300 to 400 more taps, bringing his total to around 1,000, which would make him the largest walnut producer in the state. Plus he is going to be field testing the RCBI-designed walnut-specific spouts. “I’m excited about this new tap,” he says. “We now know walnut trees behave differently than maple. Sometimes the taps back out of walnut trees when there’s freezing and thawing. This new tap is larger, has a different taper, and is made of a different material that we think won’t back out as much and leak. We hope it will give us a better flow.”

Mongold’s first batch of walnut syrup is highly coveted. During 2022 Mountain State Maple Days, people from all over the state visited his sugar shack near Petersburg’s Spring Run Trout Hatchery. He says, “That was really fun, having all these people show up to taste and purchase walnut syrup. A lot of people are curious.” He is currently developing a website for e-commerce. He even entered his syrup in the 2022 West Virginia Maple Syrup Producers Association’s Annual Maple Syrup Competition, where he took first place. “I’ve had many maple producers who’ve told me that they’ve never tasted anything like our walnut syrup, but maple folks can be diehards. It’s kind of like Ford or Chevy folks. There’s some who’d rather walk than drive a Chevy. Some think walnut syrup is better than maple, but others think it is a fad.”

Rechlin doesn’t think it is a fad. In fact, he is really excited about all the possibilities. “Will walnut syrup replace maple? No. It’s a little pricey to pour onto your pancakes. But value-added and specialty high-end products are where it’s at,” he says. “Walnut syrup is emerging as a gourmet food product and is in high demand in metropolitan areas for cocktails, candy, and gourmet ice cream toppings. There’s also a strong market for blending syrups. Some maple-walnut blends are selling for three times the price of straight maple.”

Mongold hopes he is sitting on a hillside of gold. “I’m a self-employed mechanic, and I don’t have a 401(k),” he says. “This is my retirement plan.”

Maple is a staple—but there are other sweet opportunities

Last year, the demand for maple syrup grew 35%—and that growth isn’t because we are eating more pancakes. Maple is taking center stage in gourmet products from bourbon and beer to coffee and cheese to baked goods and butter. No matter where you go, you’ll find flavor-infused syrups and value-added products touting their mapleness. West Virginia’s maple producers have taken notice and are gearing up their production to tap into this demand, and some are even augmenting their production by experimenting with other types of trees, giving way to a new niche market.

MAPLE

Indigenous people first made maple syrup, teaching it to the European settlers. Modern technological advances like the use of tubing, reverse osmosis, and vacuum pumps have revolutionized the process. While sugar maple wears the crown, other maples can be tapped, too. Each has a different sugar content and produces a slightly different flavor profile. Pure maple syrup contains 24 different antioxidants. Many maple producers have expanded into value-added products that bring a higher return on investment: A $40 gallon of syrup can be turned into molded maple candy worth $125.

WALNUT

Walnut offers an exciting new industry. While black walnut is the most tapped of this species, white walnut or butternut and English walnut are also being tapped for syrup production. Walnut syrup is typically darker than maple syrup with a more earthy, robust flavor. It is surprisingly not bitter. While there’s not a lot of research yet, it is believed that the length of the season stretches a bit longer than maple. The sugar content is similar to maple trees, and you can expect a 40-to-1 sap-to-syrup yield, but the yield is typically one-third less than sugar maple.

BIRCH

Birch syrup’s unique taste has been described as a combination of molasses, butterscotch, and concentrated apple juice. It tastes more savory than sweet. Birch beer is popular and has a fresh bite similar to rootbeer, but with a wintergreen edge. Since the sap in birch trees doesn’t start flowing until the sap flow in maples ends in April, some syrup makers expand their season by adding birch. Alaska ramped up its birch syrup production during World War I and now has a thriving cottage industry, with products ranging from vinegar to beer to soft drinks. Birch sap is considered by many to be a sweet spring tonic like mineral water, and you can find it bottled commercially in Europe, Korea, and Russia.

SYCAMORE

Sycamores are plentiful in West Virginia. These rapidly growing trees, with their unique mottled white bark, are often found along river or creek banks and aid in flood prevention. They are also sometimes planted on reclaimed coal mining areas. Sycamore tree sap has a long history of being collected as drinking water and for syrup making. The tapping season and sugar-making process are identical to maple and the sap-to-syrup ratio is similar, but a vacuum is needed. The flavor and appearance, though, are very different. Sycamore syrup looks like motor oil, and its strong taste is more like molasses with a touch of honey. It is popular in blended syrups and added to teas and marinades, and bakers love to use it in gingerbread or gingersnap cookies.

HICKORY

Shagbark hickory syrup isn’t made from tree sap at all. It is actually made from the bark that the trees naturally shed as they grow. Harvest bark that’s already detached from the tree by breaking off the hanging pieces, and then dry it. The syrup is typically made by boiling the bark in water and adding cane syrup. It has smokey and vanilla undertones and is used as a replacement for maple syrup and in glazes and cocktails.

READ MORE ARTICLES FROM WV LIVING’S WINTER 2022 ISSUE

Leave a Reply