The main hotel building at the former Salt Sulphur Springs resort in Monroe County, now nearly 200 years old, has served the same family as an elegant private residence for half a century.

Photographed by Carla Witt Ford

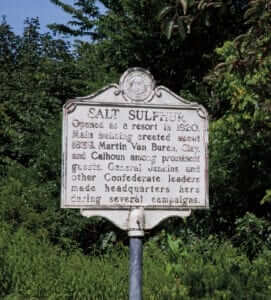

During the height of wealthy families’ summer treks to the Virginia springs resorts—from roughly 1800 until the Civil War—one popular circuit encompassed “the fountains most strongly impregnated with minerals, heat, fashion, and fame,” according to one chronicler. For those arriving from eastern Virginia and points northeast, the circuit started at Warm Springs northeast of Lewisburg, in the Allegheny Mountains. From there, it ran south and west to the Hot, the White Sulphur, the Sweet, the Salt Sulphur, and the Red Sulphur, then back in the opposite direction.

But for resort-goers from South Carolina, Salt Sulphur Springs in Monroe County—The Salt, or Old Salt—was simply the resort of choice.

South Carolinians outnumbered Virginians by three or four to one at The Salt. It served the finest food of any of the springs resorts, for their Southern tastes. The resort’s main stone hotel building held a grand, high-ceilinged ballroom with a musicians’ balcony for evening amusements. Its impressive three-story, seven-chimney, 72-room Erskine Building, added in the late 1830s when celebrated proprietors Erskine and Caruthers ran the place, was built largely on South Carolina cotton and rice money—as was its chapel, where Episcopal services took place on Sunday mornings and Presbyterian services Sunday afternoons. Distinguished visitors over the years included presidents Madison, Monroe, and Van Buren; Jerome Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon; Kentucky Senator Henry Clay; South Carolina statesman John C. Calhoun; and governors of many states.

Old Salt was famed for its three springs: sweet, salt sulphur, and iodine, curative especially for “chronic diseases of the brain” such as headaches. The resort flourished into a complex of buildings that included springs pavilions, a bathhouse, the main stone hotel building and an adjacent large stone accommodation, buildings named for both Erskine and Caruthers, a row of brick cottages, the chapel, and a store, all arranged on expansive, gracious lawns with strolling paths.

Like other inns in this part of the country, The Salt served as headquarters for both the North and the South during the Civil War. And like many springs resorts, it regained some of its former glory for a time after the war—Colonel J.W.M. Appleton managed a comeback that was surprisingly robust, given that he was a Northern officer running a Southerner-favored establishment, until he was gored by a bull on the front lawn. But the resort was unable to carry on through the Great Depression.

Old Salt sat empty for decades. Then, in 1963, Dr. Ward Wylie, a Monroe County native, longtime state senator and former delegate, and one-time president of the National Boxing Association, bought the entire complex. He and his family lived on Cottage Row, rehabilitated the main hotel building that dates to about 1820, then moved into it. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, Salt Sulphur Springs Historic District holds one of the largest groupings of pre-Civil War native stone buildings in West Virginia. Wylie’s daughter, Betty Wylie Farmer, lives there still today.

The iconic two-story portico of Old Salt’s former central building, with its seven monumental Doric columns, is thought to have been added during the resort’s second heyday of Appleton’s tenure. Ten-foot-tall windows spaced between the columns look on a wide lawn with mature trees, a true expression of the site’s gentility and old wealth.

The Wylie family’s rehabilitation of the hotel respected the architecture and earlier uses, retaining the building’s symmetrical internal structure. The front door, at the left on approach, opens on a light, airy entryway with a stairway to the second floor. Framed historical photographs and portraits line the walls—an early photo of the hotel hangs alongside images of Colonel Appleton, Confederate generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, and county namesake James Monroe.

To the right lies what must be the largest private room for many counties around: the resort’s ballroom. Larger than 30 feet by 40, the chamber centers on an ornate fireplace on the back wall; its ceiling soars to 15 feet and holds two dazzling empire-style chandeliers that hung there when Wylie bought the property. The musicians’ balcony still overlooks the dance floor. It’s a vast room but well-lit through the large windows on opposite sides, and antique furnishings break the space into intimate seating areas.

Farmer’s main living space at the far end of the house is a room that mirrors the entry hall: the former ladies’ sitting room turned to a combination kitchen, dining, and living room, furnished on the scale of day-to-day life. The modern kitchen occupies the room at the front side of the house and, at the back, comfortable seating surrounds a cozy fireplace. [rev_slider alias=”salt”]

The family’s renovations added a stairway at this end of the building, mirroring the one at the entryway. Upstairs, six bedrooms open on a central hallway, two of them with dedicated bathrooms. Decorations include items historical to the property and antiques that complement the home’s character, as well as memorabilia from Wylie’s political career and the later accumulations of Farmer’s own family.

Farmer still owns most of the Salt Sulphur property. The Erskine and Caruthers buildings deteriorated and have been demolished, and only two of an unknown number of brick cottages remain. Although the store and chapel were sold off, Farmer still has the 1820s springhouse and bathhouse that stand at the foot of the driveway, near the road. The chapel now belongs to a local group that she is a member of, and it sometimes hosts weddings. She offers her Salt Sulphur Springs property for select community events. It’s a hard property to take care of but, for her, it’s a labor of love.

“People say, ‘You could sell it and live anywhere you want to,’” she says. “I don’t know where else I’d want to live.”

Leave a Reply