West Virginia has a premier mix of outdoor recreation possibilities—so good, they can be the basis for the state’s economic and demographic rebound.

We knew it was coming: Based on the 2020 census, West Virginia is losing a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. That puts us at just two, a long slide from the six we had from the 1910s into the 1960s.

But what if I told you it stops here—that we’ll regain our third seat with the 2030 census? And easily?

It’s not an outlandish proposition and, once you’ve read this story, I think you’ll agree. It’s based on a new way of thinking about some of West Virginia’s best features and on good things that are already underway

Fun by Nature

We can trace this way of thinking to one afternoon in February 2020, when Danny Twilley and his colleague Greg Corio were seated in the majestic Keith Albee Performing Arts Center in Huntington. They were there to take in a panel about the entrepreneurial mindset. West Virginia native Brad Smith, the executive chairman and former president and CEO of Intuit, was moderating a lively conversation with the CEOs of Adobe and PayPal. It touched, in part, on how to extend entrepreneurial opportunities and the prosperity that follows beyond cities to people everywhere.

Twilley and Corio had been mulling a related question from the West Virginia perspective. Lifelong outdoor recreation enthusiasts, the two have enjoyed and led excursions in some of the most interesting terrain in the U.S. and the world. They’ve used outdoor recreation to transform people—to help them find personal confidence and make lifelong friends. They also believe in its ability to transform communities. As the leaders of a newly formed office at West Virginia University, they were charged with harnessing the university’s resources to achieve economic transformation for communities across West Virginia using outdoor recreation.

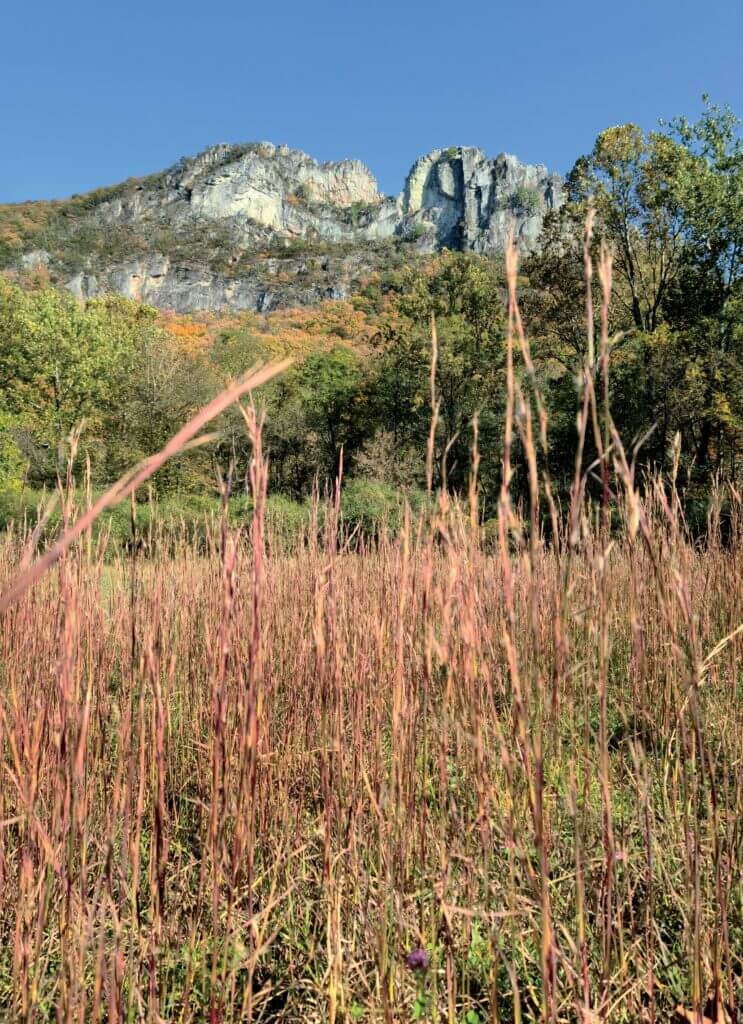

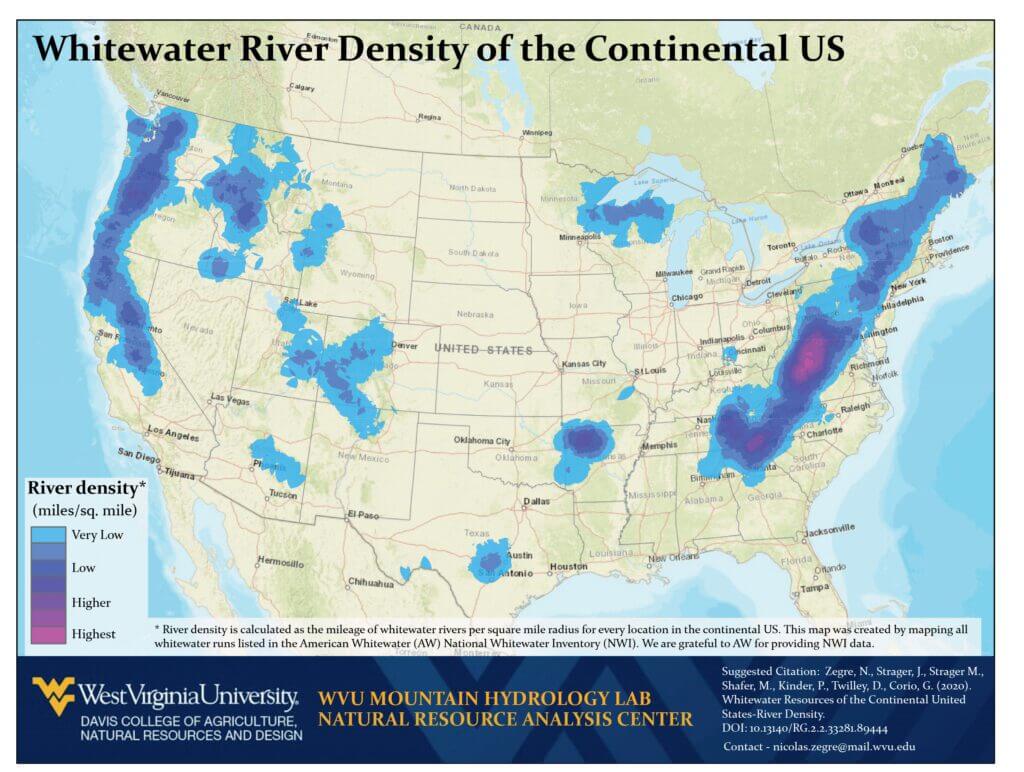

To ground their work, Twilley and Corio had been comparing places in West Virginia and in other states—looking at outdoor fun like rock climbing and whitewater rafting and how close it is to the places where people live. “We looked at places that had really leveraged their outdoor recreation resources for positive transformation, like Western North Carolina, Utah, and Colorado,” Twilley says. “And West Virginia compared really well.” In fact, the pair found that communities in West Virginia sit closer to more high-quality outdoor adventures, and a greater variety of them, than most communities.

They knew that was huge. Because, while parts of West Virginia are finding good success with outdoor recreation, other states show that far more can be done: From 2012 to 2017, Twilley says, Colorado’s and Utah’s outdoor economies grew by about 30 percent. Oregon’s grew by 24 percent. West Virginia’s grew just 1 percent—49th in the nation. Given their new data about the state’s surpassing wealth in outdoor resources, they knew there was incredible economic potential to be tapped.

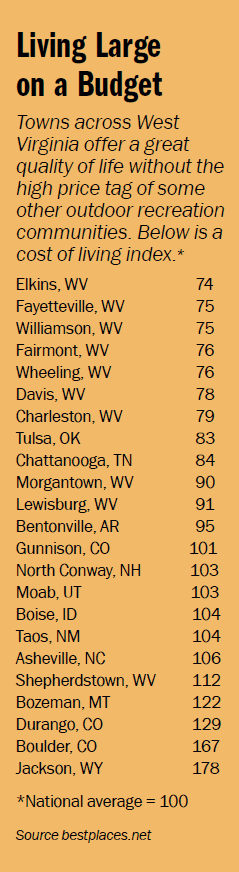

But knowing that, how do you turn it into opportunities for West Virginians? What do you do next? Twilley and Corio had been pondering that question together for weeks when they heard Smith, near the end of the CEO panel, bring up Tulsa, Oklahoma. Tulsa had launched an incentive program in 2018, Tulsa Remote, to invite people who could do their jobs online from anywhere they want to live to do them in Tulsa. That program had attracted hundreds of talented new residents in its first year.

“Brad talked about how Tulsa found out that, along with being able to afford their homes and not having long commutes, Gen Z and millennials like the outdoors,” Twilley says. “Greg and I just looked at each other. We were like, ‘Outdoor rec? Tulsa?’” In all their careers in outdoor recreation, Tulsa had never appeared on anyone’s outdoor destination list. “Nothing against Tulsa, but we knew what West Virginia was sitting on.”

Tulsa did have the right idea, though, they thought: Attracting outside talent would be a way to start in on their work in West Virginia—a good first step. And they would use the state’s premier outdoor recreation as the draw.

Twilley and Corio soon contacted Smith, an idea guy whose dedication to the Mountain State and its future runs deep, to bounce it all off of him. They showed him how other states’ outdoor economies were skyrocketing. And they laid out the numbers demonstrating that most outdoor places across the U.S. offer one signature adventure, or maybe two. “But in West Virginia,” Twilley remembers telling him, “we’ve got both whitewater and climbing. Those things are valuable, rare, and hard to imitate. And we can build more trails. That’s a trifecta—very few communities in the country can do all of that.”

They didn’t even get to the part about attracting remote workers. “Part of the way through,” Twilley says, “Brad takes off his glasses and leans forward and says, ‘Guys—this is the most exciting idea I’ve heard for West Virginia.’”

By the fall of 2020, Smith and his wife, Alys, donated $25 million in support of Twilley and Corio’s office at WVU, now known as the Brad and Alys Smith Outdoor Economic Development Collaborative. The work of the Smith OEDC is to create collaborations between the university’s deep well of resources, other nonprofits, and interested communities across the state. The idea is to develop the communities’ outdoor assets and, through business attraction, entrepreneurship, and tourism, leverage them to create vibrant economies with opportunities for everyone.

Riding The Wave: the New River Gorge area

Places across the state are at various stages of this work already, some of them well along the path—the New River Gorge area, for instance.

In the late ’80s, counties east of Kanawha saw the writing on the wall: They weren’t going to be able to rely solely on the coal economy forever, says Jina Belcher, executive director of the New River Gorge Regional Development Authority (NRGRDA). There was some timbering in the area. They had good whitewater, too, and the New River, with its iconic bridge and gorge and its National Park Service cachet as a national river. Four counties—Fayette, Nicholas, Raleigh, and Summers—banded together and formed the NRGRDA, the first regional economic development authority in the state. Each county brought something different—outdoor potential in Fayette and Summers, industrial commerce in Raleigh, and a mix in Nicholas—and the NRGRDA would work to develop their strengths together.

What has followed is a great demonstration of the early potential of developing the outdoor economy. Persistent, savvy collaboration and investment have grown the area’s outdoor recreation resources from a rag-tag collection of pioneering outfitters to world-class, multi-activity resorts within a growing ecosystem of related attractions, dining, and lodging. Today, the area’s extensive whitewater, rock climbing, and other recreational amenities are the object of admiration and pride across the state.

And in December 2020, the New River Gorge National River was redesignated the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve. “This is really a big deal,” says state Tourism Secretary Chelsea Ruby. A new national park is a rarity, she points out: Ours is only the 63rd, and more than half were created with the system itself a hundred years ago. “When Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was redesignated a national park in 2019, their visitation increased by more than 20 percent in that first year. I think we’re going to see huge, huge numbers similar to that, because this is really the gold standard in travel—for folks who are national parks loyalists, that designation is a seal of approval.”

All of this seems ready to turn population decline around in that part of the state. “We are experiencing an incredible uptick in folks that are ready to locate here to live,” Belcher says. “It’s been hard to find a house to buy in Fayette County recently, and we have permits for three new housing developments in Raleigh County.”

IGNITING THE ECONOMY

Leveraging outdoor assets to fire up the state’s economy is a six-element initiative at WVU’s Brad & Alys Smith Outdoor Economic Development Collaborative.

Talent attraction and retention Use the state’s premier outdoor lifestyle to attract and retain talented people in the younger generations that are choosing where to live based on quality of life first and career second.

Outdoor community development Create collaborations among local leaders, nonprofits, the state, and others and provide expertise that empowers communities to leverage their outdoor recreation resources.

Outdoor recreation asset development Develop new and enhance existing outdoor recreation assets in partnership with local, state, and federal groups, increasing access and creating a welcoming environment for everyone from beginners to experts.

Entrepreneurship and business development Through talent retention and in partnership with WVU Extension and the John Chambers College of Business and Economics, support the recruitment and development of businesses and entrepreneurs.

Talent pipeline and workforce development Develop strategic and innovative approaches to ensuring that current and future businesses have the skilled workforce they need to start and expand.

Research WVU can be a national leader in teaching, research, and service in developing the outdoor economy. Use WVU’s resources to conduct research that tells West Virginia’s story while highlighting areas for improvement.

A New Path: the Hatfield-McCoy Region

The southwestern counties are enjoying an earlier phase of a similar trajectory.

When the Hatfield-McCoy Trails system opened its first 300 miles of ATV/UTV trail in 2000, the economy of the region had long been based on coal, timber, and natural gas extraction. “It was an industrial area,” says Jeffrey Lusk, director of the Hatfield–McCoy Regional Recreation Authority. Coal was the biggest part of that, and, as in the central part of the state, its future was uncertain. Economic activity based on the region’s vast open spaces would bring stability.

The Hatfield-McCoy Trails have since grown to 900 miles snaking across seven counties, with still more to come. “We’re the largest managed ATV/UTV trail system in the eastern U.S.,” Lusk says.

The trail system is a giant magnet for out-of-state visitors and their recreation dollars. Of the 56,000 trail permits sold in 2019, four-fifths went to visitors from other states. Most trail users stay three or four nights, and a typical user from out of state spends more than $1,000 per visit.

Like a lot of outdoor recreational activities, trail use ballooned during COVID: Permit sales jumped 15 percent in 2020, Lusk says—even though the trails were closed for two months. The economic impact on the state in 2020 has been estimated at over $40 million, with nearly 500 jobs supported in communities all across the region. And the numbers are on track to grow another 20 percent this year.

All of this has transformed coal towns into tourist towns. “Now you’ve got main streets with restaurants and you’ve got hotels and resorts with cabins and campsites catering to tourists, so it’s really changed the look of many of these communities,” Lusk says.

It’s a big identity shift, but the region’s residents are embracing their new role as hosts. “A lot of places, the riders are not welcomed like they are here,” Lusk says. “There are dozens of communities here where you can ride your ATVs and UTVs downtown and dozens of shops and restaurants that are catering to them. For the riders to be welcomed and to be our primary customer, to have a place to go that sees great value in them visiting, that’s huge for them. We get amazing comments on our Facebook, and so many folks come back two or three times a year—that speaks volumes.”

While no one knows for sure until the 2020 Census community data is released later this year, Lusk’s sense is that the new tourism economy is slowing, maybe even reversing, decades of out-migration. “For entrepreneurial-type individuals that want to stay, this has broadened the types of businesses you can open in the area that have a higher probability of success,” he says. “Prior to this, it was only in the extraction industries—now it’s also in support of tourism.”

Trail users responding to surveys say they’d also like to fish and go ziplining and kayaking. Expanding recreational opportunities beyond one primary activity to multiple activities extends an area’s tourism season, and it’s a key to building an outdoor economy that will in turn support broad economic expansion, Twilley says.

Signs West Virginia’s Day is Coming

That’s the long game: broad economic expansion. Remember, the idea is to leverage outdoor recreation resources not only to develop tourism, but to accelerate robust, multi-faceted economies across the state—creating opportunities for everyone.

Belcher sees evidence that this beyond-tourism phase is taking hold—for example, in the expanding variety of employers that are submitting Requests for Information, or RFIs, to the NRGRDA in search of new sites for their operations. “We have interest from federal back office facilities and some tech-related companies,” she says. “We had a dormant hardwoods facility in Nicholas County that was acquired and is operational again. And several Maintenance, Repair, and Operations facilities have inquired about our newest development in Raleigh County, the Raleigh County Memorial Airport Industrial Park—we hope to secure an MRO there in the next couple of years, and that is based on the transferability of skills in the worker from the coal industry to the aerospace industry.”

And this is bigger still: The time is right to emphasize outdoor recreation, Belcher says, because she sees a deep shift at work in the national mindset. We’ve all heard that the pandemic has motivated workers to ditch their long commutes for clean skies and outdoor fun close to home. Employers have quickly caught on, and now, importantly for outdoor adventure–rich West Virginia, that’s showing up in their RFIs. “Pre-COVID, the questions were very tangible and logistical: How far is the site from the highway? How big is it? Does it have good electrical capacity? What’s the water situation?” she ticks off companies’ former priorities. “Post-COVID, we’re getting first-round RFIs that ask about recreation infrastructure and assets within X miles from the location they’re considering. The outdoor economy is now a component for being able to recruit external companies.”

That plays to the strengths the New River Gorge region has built up in recent decades. Those RFIs are a sign of economic expansion to come—and they also mean there’s more work to be done.

“Our mission with Ascend WV is simple: We want everyone to experience work-life balance in an exciting new way—through community, purpose, and the outdoors. You can bring your remote work to the mountains of West Virginia, a place that inspires imagination and innovation, forges lifetime alliances, and recharges personal batteries. It is Almost Heaven, right here on Earth.”Brad Smith

Some years ago, in anticipation of the day when the region’s economy would grow and diversify, the NRGRDA developed sister organizations Active Southern West Virginia to lift the health of the workforce and the WV Hive Network to provide resources to small-business entrepreneurs.

That was a good start. But the national park redesignation has kicked things into high gear, and Belcher is glad the NRGRDA has partnered with the Smith OEDC. “The OEDC really allows organizations like mine to build capacity in our outdoor industry,” she says. “With the national park redesignation, we need other recreation opportunities we can drive folks to in the area surrounding the gorge, so we’re not just overrunning the place. And there’s no way I could ever hire certified trail developers or the mapping folks that the university has. The OEDC is helping us identify and support the development of additional recreation infrastructure.”

And that frees her organization’s resources up to prepare the ground for the National Park bump and the broader economic growth to follow. “We know that the infrastructure needs to be upgraded. We need lodging, restaurants, outfitters, all of the components it takes to support the outdoor economy as a whole. We have to make sure the communities here are prepared for the influx of tourists and residents so we can spread the wealth of the Gorge to the gateway communities of the region—ensuring they have adequate water, sewer, and broadband access.”

These are exactly the tasks that face a growing population and economy—early signs of demographic rebound.

All Parts of The State Can Do This

One way to think about the potential across the state is to consider the nine travel regions that West Virginia Tourism has outlined, each one geographically unique. As the range of recreational opportunities in each region is expanded, Tourism Secretary Ruby says, people can visit each of the regions in four different seasons and have four very different experiences.

Places in the Potomac Highlands we used to associate with winter alone are a great example. “Folks used to talk about Canaan and Snowshoe as just ski resorts, and now those are very much four-season destinations,” Ruby says. “Now, at Canaan, you think about hiking, and I’d tell you people are starting to look at places like Snowshoe for mountain biking—the 2019 Mountain Bike World Cup was held there, and it’s returning in 2021.”

Today’s mix of snow sports, cycling, hiking, paddling, and fishing in the Potomac Highlands, much of it world-class, figures into big wins like Virgin Hyperloop’s announcement in October 2020 that it has chosen a site in Grant and Tucker counties for its coming certification center. The center will employ thousands, many in high-tech jobs.

Would developing our outdoor places in order to invite more people into the state change us in ways we don’t like? It could, if we did it inauthentically. It can also make us more authentically and proudly who we are. “There’s already a great deal of people riding ATVs here—we just enhanced and commercialized an activity that was already going on,” says Lusk of southern West Virginia. “The trail system has invigorated our small towns and allowed businesses that local residents use every day to stay open, so overall we’ve had nothing but a positive reaction to the trail system being here.” He feels there’s no better way to add a layer to a rural community’s economy. “Hiking, mountain biking, trail tourism, boating, river trails—every community in West Virginia has some natural assets close by that they can build off of.”

Belcher notices positive sentiment in the New River Gorge region, too. “I think the general consensus is that the growth of our outdoor economy definitely makes things better,” she says. “I can honestly say that folks in our region want so badly to show folks outside the region how great it is here.” For other places looking to develop their recreation resources, she recommends a multi-county approach and attention to planning. “Identify the assets you already have and look at the comprehensive picture before you start, because developing in a silo is not going to see the impact that a more comprehensive approach would.”

Wild, wonderful West Virginia’s mix of outdoor places is unique in the world, an ever-renewable natural resource of unlimited appeal. “Travelers can come here today to find the best ATV trails, the best mountain biking trails, the best hiking, the best whitewater,” Ruby says. “We see people flocking to areas where we have great experiences. And places that people have been used to vacationing in are now becoming areas where they’re looking to move to or to purchase second homes in. We’ve seen this year great increases in real estate across the state, because people are realizing that we have this unbelievable quality of life here in West Virginia.”

That sounds like the beginnings of a lasting demographic and economic renaissance, if we manage it wisely.

“I tell people all the time, the work I’m doing today isn’t for me—it’s for my kids and the youth of West Virginia,” Twilley says. “In 20 years, they won’t feel like they have to leave—they’re going to feel like they can stay in West Virginia and have the economic, social, and educational opportunities they need.”

Talent Attraction and Retention: Ascend WV

Announced in April, Ascend WV offers a package of support to remote workers who want to bring their online jobs to West Virginia. The program touts the state’s abundant outdoor adventures as the foundation of a high quality of life, and is hosted by the WVU Brad and Alys Smith Outdoor Economic Development Collaborative and the state of West Virginia.

To offset the cost and inconvenience of moving, Ascend offers participants $12,000: $10,000 in monthly installments in the first year, and $2,000 at the end of two years.

That gets them here. But to help them plug in, the program offers a co-working and networking hub where participants can connect with activities in their communities and take advantage of WVU’s entrepreneurial resources—a significant perk for any who have the ambition to start a business. And at the heart of it all is an active schedule of recreational outings—lunchtime bike rides, after-work paddling trips, weekend hiking, climbing, and whitewater excursions in the state’s most beautiful places. Two years will give participants the best opportunity to learn about all that their new community and state have to offer them and to choose to become forever West Virginia residents.

The first Ascend phase takes place in Morgantown. One month after launch, the program had attracted more than 6,500 applications. Fifty applicants, people who value community and love the outdoors, will be invited by mid-summer. Lewisburg and Shepherdstown programs will be launched in a second phase, with other West Virginia communities to follow.

Meanwhile, some communities across the state are appealing to remote workers independently of Ascend, with and without incentives. Programs like Come to Beckley, Charleston Roots, Marion Remote, and Wheeling: Live Here are promoting the charms of our state’s communities to aspiring West Virginians by choice.

Leave a Reply