Walkability, a rocking food scene, and a community of friendly people make Richwood a highly livable town.

photographed by MICHELLE ROSE

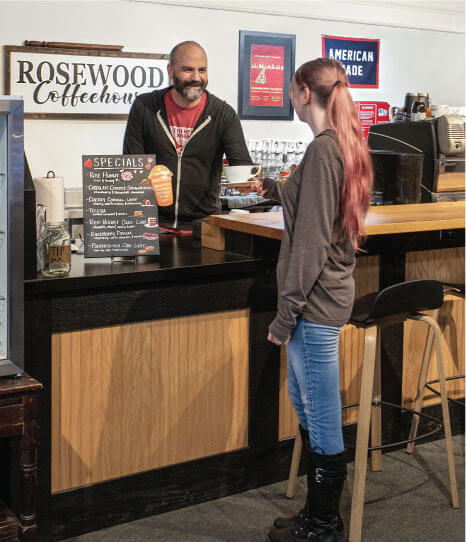

It’s 6:45 a.m. in Richwood. Local native Jeromy Rose, owner of Rosewood Coffeehouse, lists on his chalkboard today’s specials: Ginger Praline Latte. Chai with Winesap apple. Espresso with Peanut Butter Fudge. By 7 a.m., Rosewood’s first customers come in, tourists staying up the street at the stylish La Bonita Airbnb. La Bonita is owned by David Ward, a Richwood native, and his husband, Cecil Ybanez, from the Philippines.

At 7:30, Chuck Toussieng pops in for his usual: espresso over ice. Toussieng is a computer coder who owns another Main Street business, Richwood Scientific. The Los Angeles native married a veterinarian from nearby Summersville. When he came home to meet her family, he was captivated by Richwood’s potential as a gorgeous location for working remotely. “When I found out that in Richwood you could buy a house with five acres and a stream for less than I paid for my truck, I was interested.” Ten years later, he’s a model for “living where you work and loving where you live” in West Virginia.

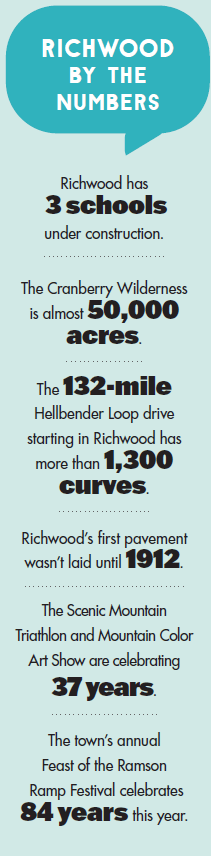

Seven years after the devastating “1,000-year flood” of 2016, Richwood is humming with new energy and synergy. The 120-year-old former industrial hub is reinventing itself as a popular destination for foodies, artists, and adventure seekers—nearly 40 new small establishments have sprung up in the past seven years.

Among the newcomers former Floridians Ybanez and Ward, who sold their home in a tony Miami neighborhood at the height of the pandemic. Interestingly, it was Ybanez who had to convince Ward to move back to his hometown. Ybanez was interested in a hundred-year-old Craftsman-style lodge from the city’s industrial heyday. “I took one look at the vaulted ceiling and said, ‘this is it.’”

While engineer Ward travels for his work as public utility salesman, interior designer Ybanez curates exhibits of Appalachian artists at his high-end gallery, Bloomfield Richwood. An aspiring artist himself, he has seen his own career bloom here: He was recently awarded Best of Show in the 2022 Emerging Artists Series at the West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture, and History.

Why Richwood for this unlikely couple? “Richwood is a hidden gem at the edge of the Monongahela National Forest,” Ybanez says, citing the low cost of living. He and Ward are avid hikers and they love the eateries: “much more variety than you would expect from a tiny town of 1,800.”

It’s 8:30 a.m. Joy Smith is feeding a lively breakfast crowd of loggers, tourists, and locals at her popular Oakford Diner. Out comes a Western omelet with extra salsa for Ian Gladwell, his usual. After earning a pharmacy degree from WVU, Gladwell married his high school sweetheart and came back home to Richwood. Just 28, he recently opened his own business, Cornerstone Pharmacy on Main Street.

On the stool beside Gladwell sits Police Chief Dan Pitts. He and his wife, Robin Pitts, a business consultant, were looking for a change of pace after he retired from the police force in a suburb of Cleveland. On a whim, Pitts answered an ad on indeed.com in West Virginia, where his wife’s family had roots.

It was a big change for the lifelong Ohioans. “My friends told me I was crazy,” Dan Pitts says. “But I instantly felt so welcome here.” The Pittses particularly love the town’s walkability. They rent a charming cottage in the center of town, where she works remotely.

Robin Pitts was quick to answer the question “Why Richwood?” “We were surprised to learn how many of our interests clicked with what the town had to offer.” She loves yoga and antiques; he loves golf, hunting, and fly fishing.

Location is Richwood’s biggest asset. The city limits blend seamlessly into the Monongahela National Forest, with nearly a million acres of natural beauty. Add to that its location halfway between the New River Gorge Bridge National Park and Snowshoe Ski Resort, and clearly Richwood is poised to reap rich benefits in the growth of tourism as well as from its traditional timber and coal assets.

But Richwood wants to be more than a tourist destination. City leaders want to attract more people to live and work here.

Enormous investments in infrastructure—upwards of $50 million—are setting that stage. By 2025, the city will have a brand new K–12 school, replacing those closed by the flood. In the meantime, the town will see a flurry of construction activity in the coming months including expansions and upgrades to its sewer system, water system, sidewalks, city parks and pool, broadband, and community centers.

The challenge for Richwood is housing. The demand is urgent for lots, long- and short-term rentals, single family dwellings, vacation homes, and commercial property. But the flip side of challenge is opportunity. Those with the means and the know-how are restoring old homes and storefronts with stunning results. Nearly a dozen new homes have been built where old ones were torn down.

It’s 9 p.m. Joy Smith can be seen flipping the chairs onto the tables in the Oakford Diner and mopping the floor. Just four doors down, at the Oakford Pool Hall—no relation to the diner—a lively crowd is gathering for “Thirsty Thursday.”

A popular waitress at the Oakford Pool Hall is Heidi Schultz, who came here two years ago from Cypress, California. “There was something magical that drew me here,” she says, filling a frosty mug with a regional craft beer favorite: Cougar Bait. “Never have I met nicer, friendlier, more helpful, genuinely good people. If you have that quality where you genuinely care about people, you stay.”

Leave a Reply