West Virginia’s Eastern Panhandle is home to several historic houses with ties to our founding father.

Colonial Virginia was always looking westward. Generation after generation of colonists wanted their own land. And as tobacco, the colony’s moneymaking crop, wore the soil out, planters, especially, sought new ground.

In that environment, surveying was a promising profession for a young George Washington. And he was perfect for it. He had a mind for maps and math. He had the best possible connections: His older half-brother Lawrence had married a Fairfax of “Fairfax Grant” fame—some five million king-granted acres extending westward to the source of the Potomac River, just waiting to be surveyed into tracts and sold off.

And his timing could not have been better. The long-disputed Fairfax boundaries were fairly well settled in 1746, when George was 14. Lord Thomas Fairfax was ready to sell in earnest and, in 1748, his agent hired George as part of a Shenandoah Valley surveying party. George and brother Lawrence soon bought up thousands of acres in the fertile region for themselves.

Then, in 1752, Lawrence died of tuberculosis. He wrote George from his deathbed of their shared hopes for backcountry Virginia: “I agree that the Shenandoah Valley is one of the most pristine areas and likely to advance your fortune quite nicely.” Lawrence left his Shenandoah Valley acreage to their younger brothers, Samuel, John, and Charles.

This is how the Washington family came to what is now West Virginia’s Eastern Panhandle. On that early legacy, the brothers and their descendants built sturdy homes that still stand. As the only one still in Washington hands a quarter-millennium later, Harewood, just west of Charles Town, is arguably the gem.

Samuel Washington was prominent in his own right before George became commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in 1775 and long before George was president. “In 1766, while he still lived in King George, Virginia, Samuel was one of the first signatories, along with brothers Charles and John, of the Leedstown Resolves, protesting the treatment of the colony by Parliament,” says Samuel’s great-great-great-great-great-grandson Walter Washington, who lives at Harewood today.

Soon after, Samuel and family were the first Washingtons to move to the Shenandoah Valley. Their Harewood dazzled. “When that house was built, in 1770, it was by a long shot the fanciest house in the valley,” says Charles Town architectural historian John Allen. The combination of style and materials was unique. “It’s very similar stylistically to the Tidewater houses where the Washington family came from, literally transplanting that culture here,” John says. “But there wasn’t really any brick here at the time, so they built it out of the local limestone. It really is unusual.”

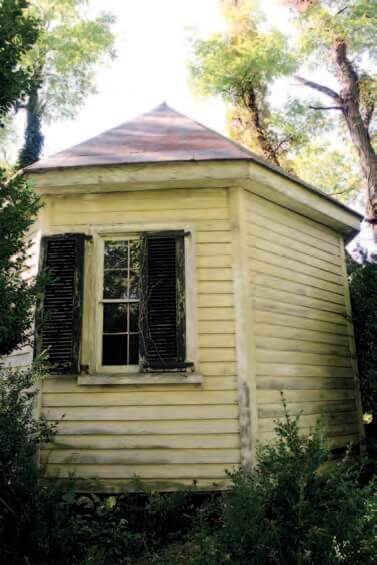

Samuel’s stone house looks an austere gray in some lights of day and a warm brown in others, but it always carries a formal Georgian dignity. The main house, one room deep, centers on a high foyer: The visitor entering from the east faces a three-sided staircase that ascends from the left up and over a west-side doorway, turning back on itself to reach a second floor. To the right is a grand drawing room that we’ll revisit in a moment. To the left, the dining room and, through that, a south wing—a large kitchen connected by an architectural “hyphen.” Upstairs, there is a bedroom at either end with a hall between. That’s the whole of the original house that Samuel, wife, and three children moved into.

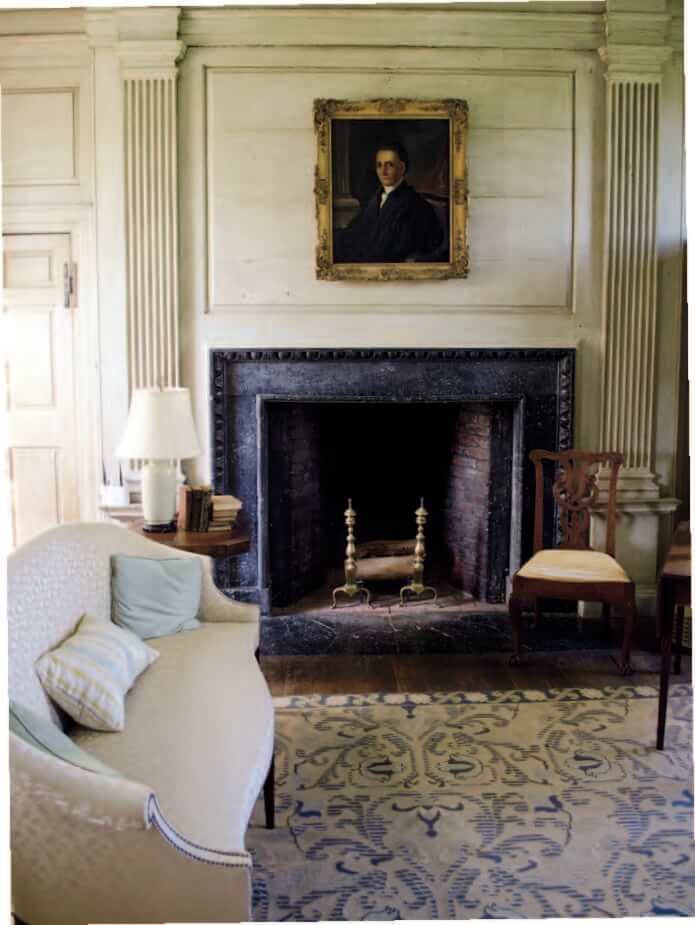

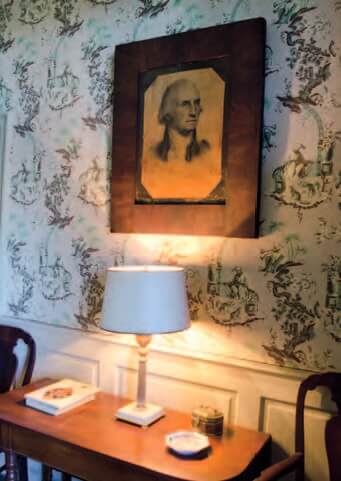

We can easily imagine the drawing room of the 1700s, because it hasn’t changed—even the paint is original. This 20-by-20-foot space is where the Washingtons would have entertained. It luxuriates in the full daylight of rooms that have windows on opposite sides. The classic millwork and 12-foot ceilings would have made for gracious gatherings.

Samuel grew wheat and served as a colonel in the local militia and, after Berkeley County split off from Frederick County, Virginia, he was sheriff. But the family struggled with tuberculosis and, by 1783, the children were orphaned. Uncle George took responsibility for two: George Steptoe and Lawrence Augustine. Harewood may have stood empty—“That’s a good question. We don’t know,” Walter says—while George finished the War of Independence, became founding president in 1789, and saw his wards raised and educated. But in 1793, George Steptoe and his wife Lucy moved into Harewood. Lucy’s sister Dolley was wedded in the drawing room the following year to James Madison, later the nation’s fourth president. Lucy’s pianoforte, which surely brightened festive occasions, remains in the room as a reminder of those times.

Washingtons occupied Harewood until they moved to nearby Charles Town in about 1900. Tenant farmers lived there for 50 years until Walter’s parents decided, when he was 3, to restore it. “I remember paint peeling off the walls and ceilings,” he says. “That hyphen between the house and the old kitchen, which had a rough lean-to screen porch, there was a groundhog living under the steps.” He visited weekends and summers as the work progressed. At some point, a cousin added a tasteful mirroring north wing.

Some stories about Harewood are undocumented—like a visit from the exiled future French king Louis Philippe. “That’s an urban myth,” says Walter, who read the monarch’s diary. “He did come to Charles Town, but he never mentioned coming to Harewood.” While people perpetuate the story that George’s friend the Marquis de Lafayette gave him the marble mantelpiece in the drawing room, John says there’s no proof of it.

Walter shows Harewood occasionally to those with expertise in history and architecture. He has secured the property’s future by selling a conservation easement, putting the funds into a trust for maintenance, and enlisting cousins in Ohio to steward the home after his time.

Charles Washington moved to the Shenandoah Valley a decade after Samuel, in 1780. He built his home, Happy Retreat, just a few miles from Harewood and set aside an adjacent 80 acres to form Charles Town. When Jefferson County split off from Berkeley County in 1801, Charles Town became the county seat.

Happy Retreat changed hands a number of times and, by the time of the real estate boom of the early 2000s, its 12 acres were in danger of subdivision and development. The nonprofit Friends of Happy Retreat (FOHR) bought the house in July 2015 to preserve it.

“It’s a complicated house,” says Walter, who serves as president of FOHR. “Charles Washington built the two wings, each one and a half stories high, facing each other. The main portion of the house was built in the 1830s by someone unrelated to the family, local Circuit Judge Isaac Douglass. So the central portion, which everyone identifies as Happy Retreat, was not built by Charles.” That central part remains unchanged, but for the addition of bathrooms. The east wing was long ago gutted and rebuilt. “But the west wing, we believe, are the two rooms Charles lived in, so we’re focusing our restoration on that part.”

In a commitment to seeing Happy Retreat a living part of the community, FOHR is turning it into a cultural center for concerts, plays, and art exhibits, Walter says. The addition of a catering kitchen will outfit the estate for event rentals, and an interpretive center will make it a heritage tourism destination.

“Everyone concentrates on Jefferson County’s Civil War history and John Brown, but there’s an earlier history, too,” Walter says. “People don’t realize we also have the homes of two other Revolutionary War generals in Jefferson County, Horatio Gates and Charles Lee. All of us involved with this effort on Happy Retreat are committed to seeing that earlier story told.”

Blakely and the facing Claymont Court were built by brothers John Augustine and Bushrod Corbin Washington, grandsons of the president’s younger brother John Augustine, between 1815 and 1820. The family story is that John Augustine built Blakely smaller because he knew he would inherit Mount Vernon. “But even when they lived at Mount Vernon, Blakely is where they came to get away from the August heat,” says Walter Washington. Blakely is in private ownership and closed to the public.

The original structure was built by Thomas Beall in the late 1700s. Beall passed the home to his daughter Eliza and son-in-law George Corbin Washington, the grandson of President George Washington’s older half-brother Augustine and a two-time U.S. congressman. The large main Classical Revival portion was built by George Corbin’s son, Lewis. The home is owned today by a developer and stands behind a fence in a gated community.

The grandest home in the region, Bushrod Corbin’s Claymont encompasses some 16,000 square feet. “There probably were homes in Virginia that were that big but certainly nothing in the Shenandoah Valley that even came close to that big,” says local architectural historian John Allen. The current Georgian structure, dating to about 1840, replaced the original after it was destroyed by fire. It is owned today by the Claymont Society for Continuous Education.

Built about 1825 by Samuel’s grandson John Thornton Augustine on a portion of the original Harewood estate, Cedar Lawn was bought in the 1940s by the industrialist R.J. Funkhouser, who at one time also owned Claymont Court and Blakely. It has been restored by the current owners, Taylor and Marjorie Fithian, and is not open to the public.

Leave a Reply