Knowing Morgantown’s back roads, cut-throughs, and workarounds is what distinguishes those who’ve lived in Touchdown City from those who’ve only visited. But no town gets to be 200-plus years old without burying some secrets. You don’t really know Morgantown until you know what lies beneath it.

Falling Out of Sight

Falling Run starts in the heart of the West Virginia University Organic Agriculture Research Farm off State Route 705, about a mile from the Monongahela River as the stream trickles. The valley it drains separates the Woodburn neighborhood from Sunnyside and Wiles Hill, and it’s so deep that, a hundred years ago, people crossed it on a long, high wooden footbridge. Although we circumvent that valley today, it’s still one of the main reasons it’s so hard to get across town—we drive around it either above the headwaters, on 705, or on University Avenue near the stream’s outfall into the Mon River.

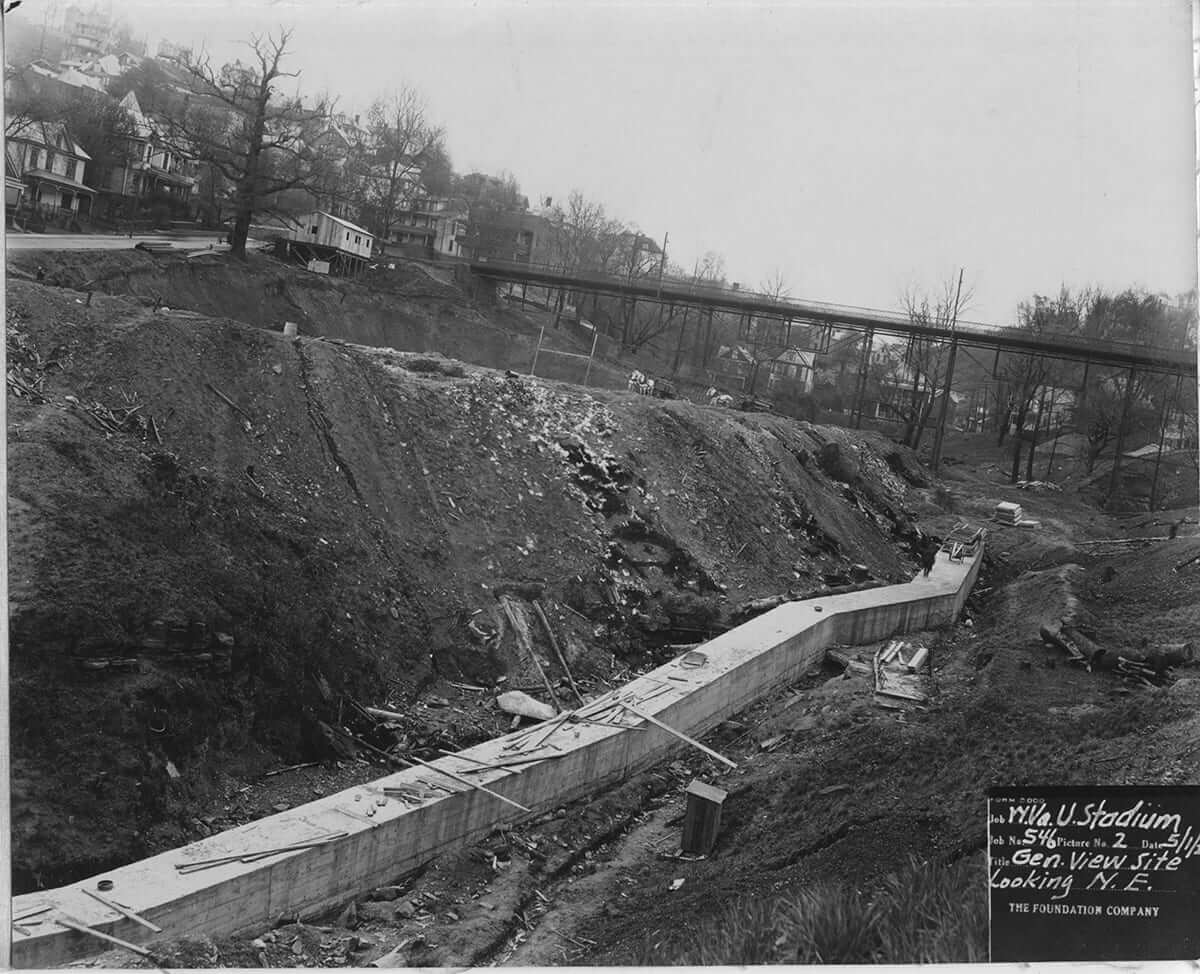

But where is Falling Run when University should be crossing it, at the bend near WVU’s College of Business and Economics—at the intersection with Falling Run Road? “Falling Run used to run back behind Woodburn Hall. But when they built the old Mountaineer Field in the ’20s, they channeled Falling Run underground,” says Morgantown Utility Board spokesman Chris Dale. “In the old photos, you can see the concrete box culverts they built—which are still there.”

Falling Run’s outfall into the Mon River can still be found. A brick archway opening to a surprisingly large tunnel bored into the stone can be accessed by wooden steps leading down from the Caperton Trail a little north of Stansbury Hall.

Rebel Jail

Exploring under the Berman building with a flashlight, accompanied by the owner, it’s possible to identify one wooden cell with bars and at least two sets of bars that are part of a confusing layering of older and newer walls. The people most familiar with the city’s history don’t know why there would have been a jail separate from the county jail. “Maybe they had more people than the regular jail would hold—they might have used it as an auxiliary jail,” Pamela Ball, chair of the Morgantown Museum Commission and director of the Morgantown History Museum, has speculated. “Or maybe they thought Confederate prisoners would be easy to find in the main jailhouse, but less obvious at an auxiliary site.”

Little is said of prisoners of war in Morgantown lore. But here’s a charming story from the same time period that likely refers to the county jail. In the wee hours of May 6, 1864, a small band of rebel soldiers made a run on the jail and released a Van Cicero Amos. Amos had been arrested in Marion County on charges of “secreting himself within our lines” according to the Morgantown Weekly Post, and of stealing horses. Amos knew in advance that he would be busted out. In an odd twist, before his compatriots arrived and “without any ceremony smashed the locks,” he composed a letter to his jailkeeper, a Mrs. Stewart. “To-night I leave you. I would stay and see my trial through with, but the Union party are using all influence against me that they can, trying to prove a thing which I am not guilty of,” Amos wrote. His trial was scheduled for the following week. “I will be relieved by five or six confederate soldiers, who come expressly to release me. They will also accompany me to Dixey. Prison is not for the innocent.”

Steamy Underbelly

In Jules Verne’s novel about Morgantown, a WVU professor discovers giant serpents that survived the Cretaceous extinction by taking up life in steamy burrows under the city.

Okay, Jules Verne never wrote about Morgantown. But anyone who’s lived here has heard of the steam tunnels. The name is pretty self-explanatory: a network of utility passages that conveys steam to WVU buildings for heat. But it’s also evocative: Do they snake all through campus? Are they muggy, like an underground greenhouse? Do tropical slimes grow on the walls? We got a look inside.

It turns out, the tunnels are not filled with steam. But they are a warm, hissing, winding, neon-lit burrow worthy of a sci-fi novel, filled mostly with pipes that carry steam. Gauges and valve handles of all sizes and vintages sprout here and there from the conduits. The level of the stone and dirt floor in the main, walkable tunnel changes unexpectedly with the occasional puddle that is inevitable underground, but it’s mostly dry. The air is dry, too, and odorless, and the walls are completely free of tropical growths.

Some readers who’ve lived in Morgantown will remember an old coal boiler plant that stood next to Stansbury Hall. It generated the steam it sent through tunnels to WVU’s downtown buildings, according to WVU Facilities Management Director of Maintenance Daniel Olthaus. The original, walkable main tunnel runs from beneath that old boiler plant to near the Mountainlair, and smaller tunnels branch off from there to all the major downtown campus buildings—about a mile of tunnels altogether. The function of the boiler plant was taken over by the Morgantown Energy Associates (MEA) plant a half-mile away after it was demolished around 1990. Evansdale was served earlier by its own boiler and buried pipes, and is now served by MEA as well.

The tunnels are very carefully maintained: Facilities Management performs upgrades throughout the tunnels on a three-year cycle, and someone from MEA walks the tunnels every day. Over time, the tunnels have taken on other utility functions as well: water, telephone, fiber, and electricity. No worries about dinosaur-era monsters escaping: The entrances are well sealed.

Time, Encapsulated

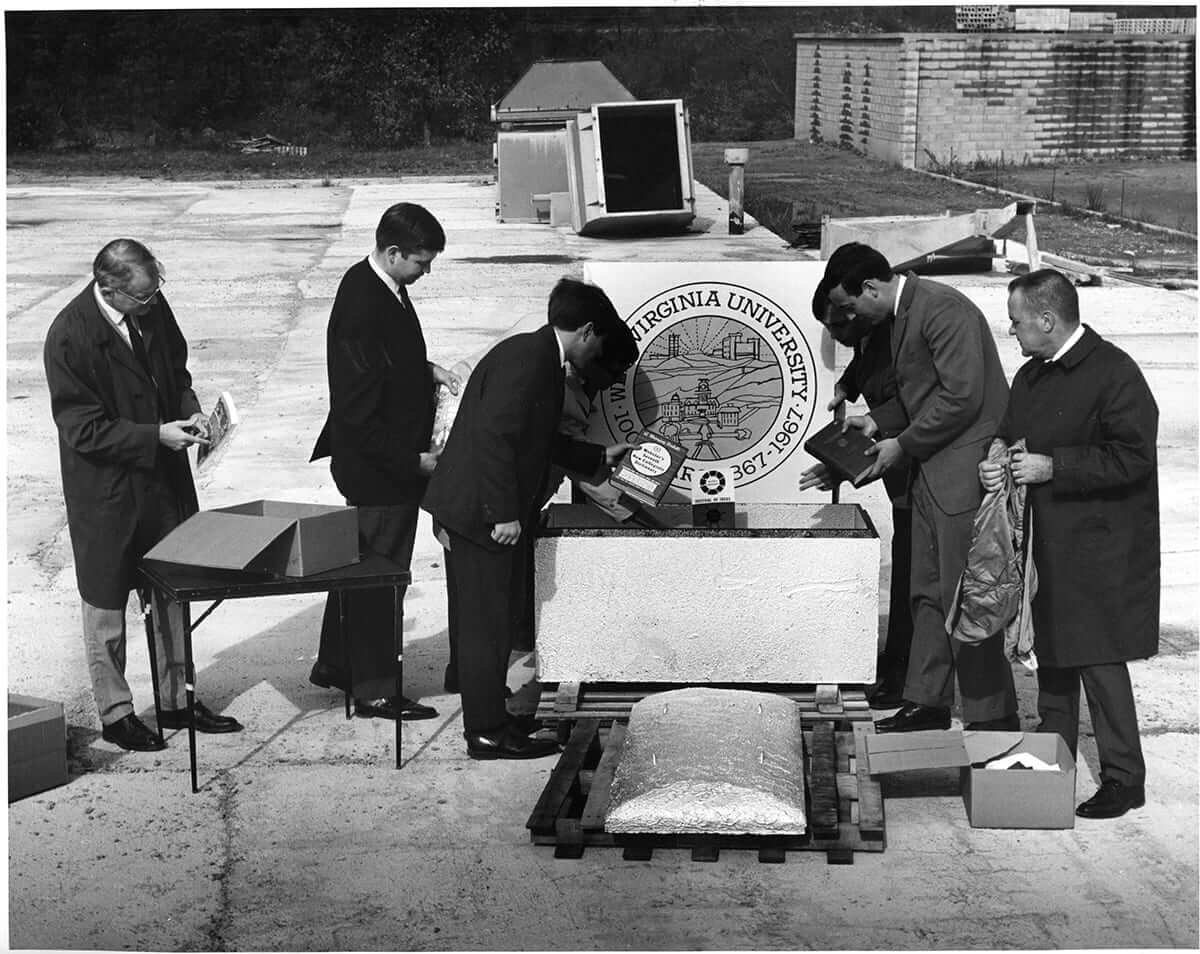

Every once in a while, humans get the grand idea of communicating with their descendants. That happened at least twice in Morgantown in the latter half of the 20th century, resulting in two time capsules buried within 20 years and a few hundred yards of each other.

Coming due in 2067 is the WVU centennial time capsule. Created in 1967 as part of the university’s centennial celebration, the time capsule—which, in photos in WVU’s West Virginia and Regional History collection, looks like a small concrete coffin—was originally buried under Memorial Plaza in front of Oglebay Hall. It was moved during construction to a spot in front of the Mountainlair.

And set to be opened in 2085 is the Morgantown bicentennial time capsule. It was buried at the steps up to Woodburn Circle from University Avenue, in Ball’s recollection. The book Morgantown

Bicentennial contains a photo of a plaque—but that plaque is now nowhere to be found at that location. “My guess is they’ve taken that away,” she offered, “maybe to protect it from vandalism.”

War-time Shelters

Underground Railroad

Escaped slaves are indeed said to have passed through the Morgantown area on their way to the Mason-Dixon line and freedom in Pennsylvania. But if you’ve heard 123 Pleasant Street was a stop on the railroad and that’s why the music club was named that in an earlier incarnation, it’s unlikely: The brick rowhouse apartment building was constructed almost four decades after slavery was abolished, in 1891.

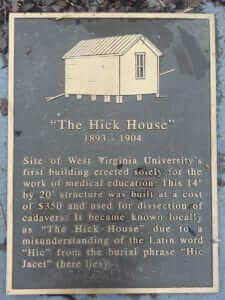

Hick Dissection

“In the early days of the medical school, WVU medical students would dissect human cadavers for study in the basement classrooms of Woodburn Hall,” Morgantown storyteller Jason Burns tells. “The cadavers were kept in the Hick House. A plaque near Woodburn documents the origins of the name. The School of Medicine says in its history online that cadavers were referred to as “hicks” rather than “stiffs.”

Leave a Reply