A look back at some of West Virginia’s female muckrakers and glass ceiling–breakers

This land at the heart of Appalachia has a rich history of strong women. We’re talking about women who’ve shown up in places they were expected to stay away from and spoken up when they were expected to be still—women who’ve made people uncomfortable in defense of family, community, public health, equity, and common sense.

Thanks to them, women today have their say in more dialogs than ever before. So as we assembled our list of West Virginia Wonder Women for 2022, we thought back to the trailblazers who made their achievements possible. This is our tribute.

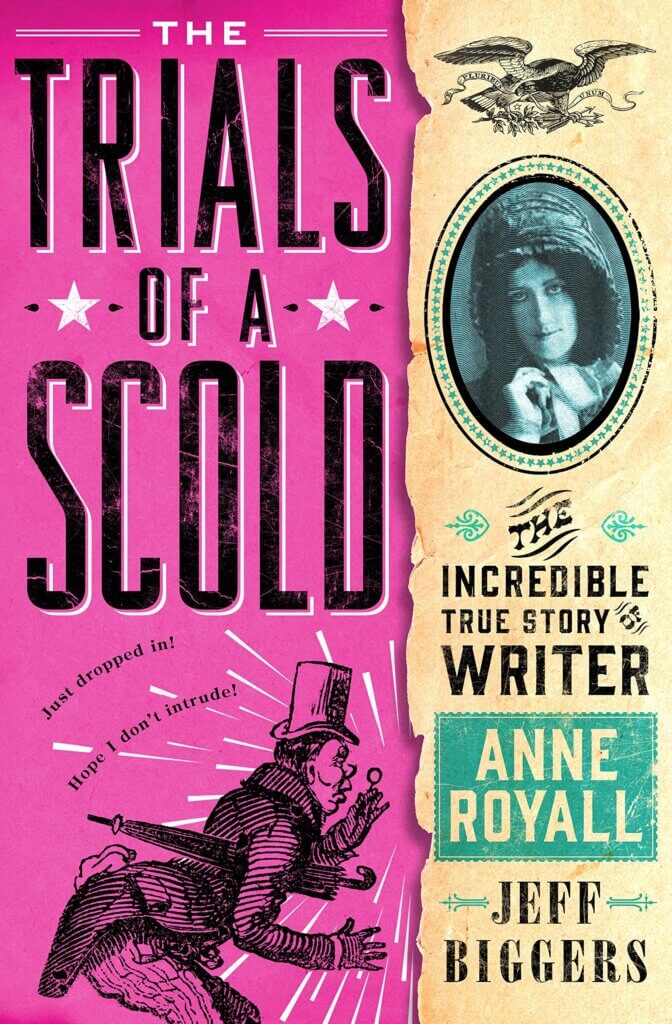

Anne Newport Royall

Telling it like it was

When Anne Newport’s widowed mother moved her family to Sweet Springs, Virginia, in the 1780s, the teenage girl’s curiosity and intelligence impressed Major William Royall, and he arranged for her education. The two were eventually married—but he left her a widow in her 40s. To support herself, Royall traveled northeastern cities, interviewing influential residents and writing carefully researched accounts for subscribers. Her books, first published in 1826, and later her newspapers, exposed corruption, fraud, and political misdealings—she made enemies.

Royall was taken to court in 1829 on charges of being “a common scold.” But history now sees her as the first of the muckraking journalists, an irreverent woman telling it like it was. More than once, the media championed her bold exercise of press freedoms: When the court found her indeed a common scold, for example, two reporters from D.C.’s respected National Intelligencer paid the $10 fine.

Belle Boyd and Nancy Hart

Using their human wiles

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Women have historically been sidelined during wartime, even though the outcome affects them just as much as it does men. But our women haven’t always been content with that. During the Civil War, Belle Boyd, who was born in Martinsburg and lived her early childhood there, acted as a Confederate spy from her father’s hotel in Front Royal, Virginia. She took big risks and was arrested at least six times. Information she passed to Stonewall Jackson in May 1862 earned her a captain’s commission in the Confederate army.

In Roane County, Nancy Hart, a teen already proficient with firearms, worked as a Confederate scout and spy. Local lore says Hart was captured twice. The first time, she persuaded her captors to release her. The second time, in July 1862, she escaped her Summersville captivity, returning a week later with 200 Confederate soldiers to capture the Summersville outpost.

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones and Sarah “Ma” Blizzard

We know which side they were on

The post–Civil War years didn’t go well for Mary Harris Jones. She lost her husband and children to yellow fever in 1867, then lost her home and dress shop to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. The advancing Industrial Revolution was imposing insufferable conditions on workers everywhere at the time, and Jones found her new family in the labor movement and took fiercely to organizing. She inspired workers and their families to act collectively, and she became known for organizing wives and children to demonstrate on behalf of striking workers.

Jones worked in states across the growing nation. In West Virginia, she walked from coal camp to coal camp to rally mine workers to unite against mine owners. By 1902, her work got her called “the most dangerous woman in America.” “Mother” Jones was jailed leading a strike in West Virginia in 1902 at the impressive age of 71—and a second time in 1913, at 82.

While Jones organized everywhere, Sarah Blizzard worked in the trenches here in West Virginia. Her family was evicted from their Fayette County home because of her work with striking miners in 1902. They moved to Cabin Creek, in Kanawha County, and became involved in the violent Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike of 1912–13. In one incident, Blizzard led women to end the terror of the Bull Moose Special—an armored train car of machine guns that were fired into striking miners’ tent colonies—by destroying the train tracks to prevent its return. “Ma” Blizzard and Mother Jones sometimes worked together in support of uniting miners.

Birth workers

Into good hands

Everywhere throughout human history, women have birthed babies outside hospitals with the help of family or friends who had learned from more experienced community members. These lay midwives took charge and made hard decisions bedside, often with no expectation of pay. And in frontier times and remote hollows—that is, much of our Mountain State through most of its history—they did it with few resources. If your great-grandparents were born in West Virginia, there’s a good chance they were helped into the world by lay midwives.

The late 1800s and early 1900s brought the steady advance of medically assisted birth. Practitioners were gradually professionalized as nurse midwives or marginalized. Practicing midwives had to be licensed annually beginning in 1926 and to practice under strict constraints. The number of licensed midwives declined from a peak in the late 1920s and, eventually, medically assisted hospital births became the overwhelming norm.

A shout out to today’s midwives, keeping knowledge of natural childbirth alive, and to the women who delivered all of our ancestors.

Lenna Lowe Yost and Irene Drukker Broh

Ain’t I a citizen?

When Congress passed the 19th amendment in 1919, it fell to states to consider it for ratification—36 were needed to make it the law of the land. In West Virginia, Marion County native Lenna Lowe Yost headed up the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association’s ratification campaign. She was ideally qualified and connected, having provided strong leadership on the issue for 15 years. The persuasive Yost lobbied state senators and delegates for yes votes, and she organized a “living petition” of residents from all across the state to show up at the February 1920 special session called by Governor Cornwell. In a tense, nearly two-week session that gripped the nation’s attention, West Virginia ultimately became the 34th state to ratify—with much credit due to Yost.

And who was the first in the state to exercise her new right? Raised by a suffragist-in-secret—her husband did not approve of women seeking the right to vote—Irene Drukker accompanied her mother to suffrage meetings in the 1880s and ’90s any time her father was out of town. In her married life, Irene Drukker Broh worked for the vote and saw the 19th amendment passed into law. On November 2, 1920, she arrived at the Kestler Garage on Fifth Avenue in Huntington in time to cast her paper ballot when the polls opened at 7 a.m. Several men in the polling place offered to put Broh’s ballot in the box for her, but no: She refused them all and placed it herself.

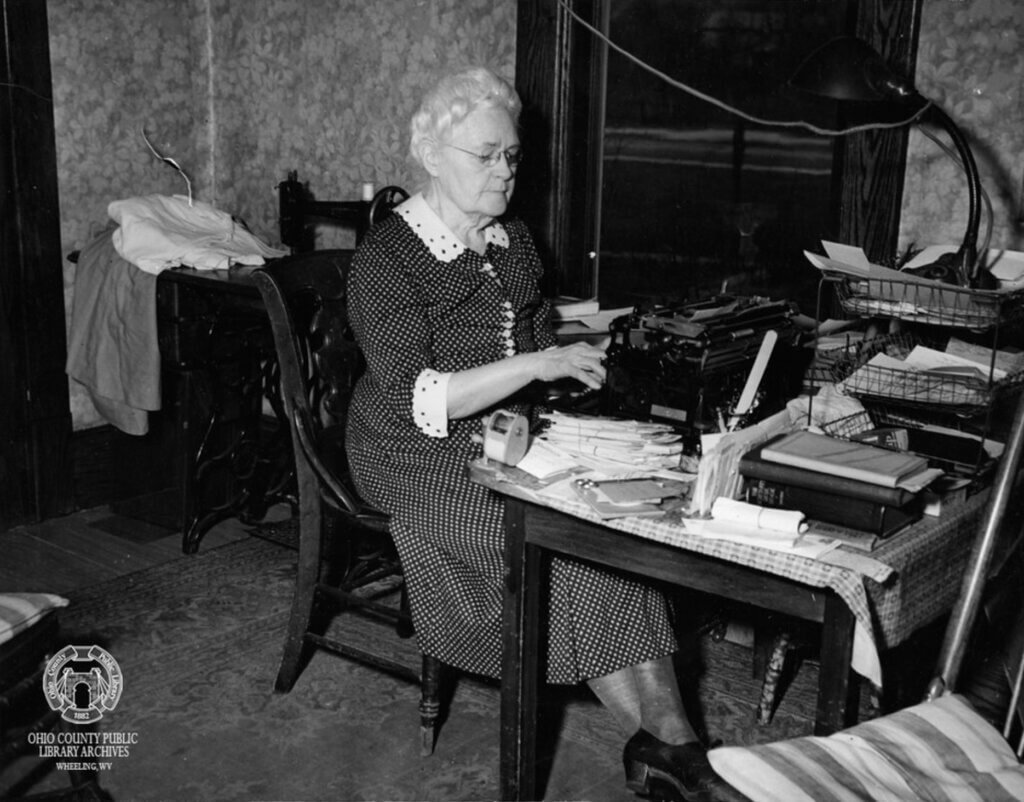

Dr. Harriet Jones

Blazing multiple trails

Many accomplished women of the late 19th and early 20th century were committed suffragists in addition to their primary achievements—among them, Dr. Harriet Jones. Jones grew up in Terra Alta in the 1860s and ’70s and pursued medical studies in Baltimore, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, specializing in gynecology and abdominal surgery. She became the first licensed female physician in West Virginia. And in 1886, she opened a private practice in Wheeling. Dr. Jones went on to serve as assistant superintendent of Weston State Hospital, then to establish a women’s hospital in Wheeling. She also served as secretary of the West Virginia Anti-Tuberculosis League.

And while she was breaking the glass ceiling in medicine and improving health care for women and for all, Dr. Jones advocated for women to be accepted as students at West Virginia University—a practice that did not begin until the institution was 22 years old, in 1889. After women won the right to vote in 1920, Jones became one of the first female state lawmakers, serving two terms as a Marshall County delegate.

At the age of 82, according to the notes kept with this archive photo, Jones still did most of her own sewing.

Hazel Dickens

Sing it, sister!

Bluegrass legend Hazel Dickens sang for those who had no voice. Born in Mercer County in 1925, she was raised in coal country in deep poverty. She followed siblings to Baltimore as a teenager and became part of a lively scene of house jams, club gigs, and, in 1965, her first record, with Alice Gerrard. Their band the Strange Creek Singers recorded one of Dickens’ first songs of social commentary in 1972, “Black Lung”—written for her brother Thurman, who’d died of the disease. Her later songs spoke forcefully for miners and for women, and she became a powerful advocate, communicating the struggles of workers and families to a wide audience. Other songs celebrated the comfort and beauty of her mountain home.

Dickens recorded 11 albums, appeared in the 1987 mine wars film Matewan, and more. She was the first woman to receive the International Bluegrass Music Association Award, and she’s received highest musical honors, including from the Smithsonian Institution.

Memphis Tennessee Carter Garrison

Teaching justice

Named for the city where her aunt worked as a teacher, Memphis Tennessee Carter Garrison started her own career as a teacher in a one-room school in Gary, in McDowell County, in 1908 and taught there into the 1950s. She also wanted to be a lawyer, and likely would have made a good one: She served as a mediator for U.S. Steel’s coal mines in Gary, resolving miners’ conflicts and concerns—at first informally and, from 1931 to 1946, on behalf of U.S. Steel.

Garrison was a community builder who set up a breakfast program for her students during the Great Depression and organized cultural events to uplift those around her. And she was a civil rights activist. In 1921, Garrison established the Gary branch of the NAACP. The Christmas Seal fundraiser she established for it out of her house in 1927 was so successful that, after four years, the national office took it over. Christmas Seal sales supported the NAACP’s work advancing the major national civil rights laws of the 1950s and 1960s.

Garrison retired to Huntington in 1952. She established a Black Girl Scout group there and served the national NAACP organization, including as its vice president. Her legacy was stronger children, a stronger Black community, a stronger West Virginia, and a stronger Appalachia.

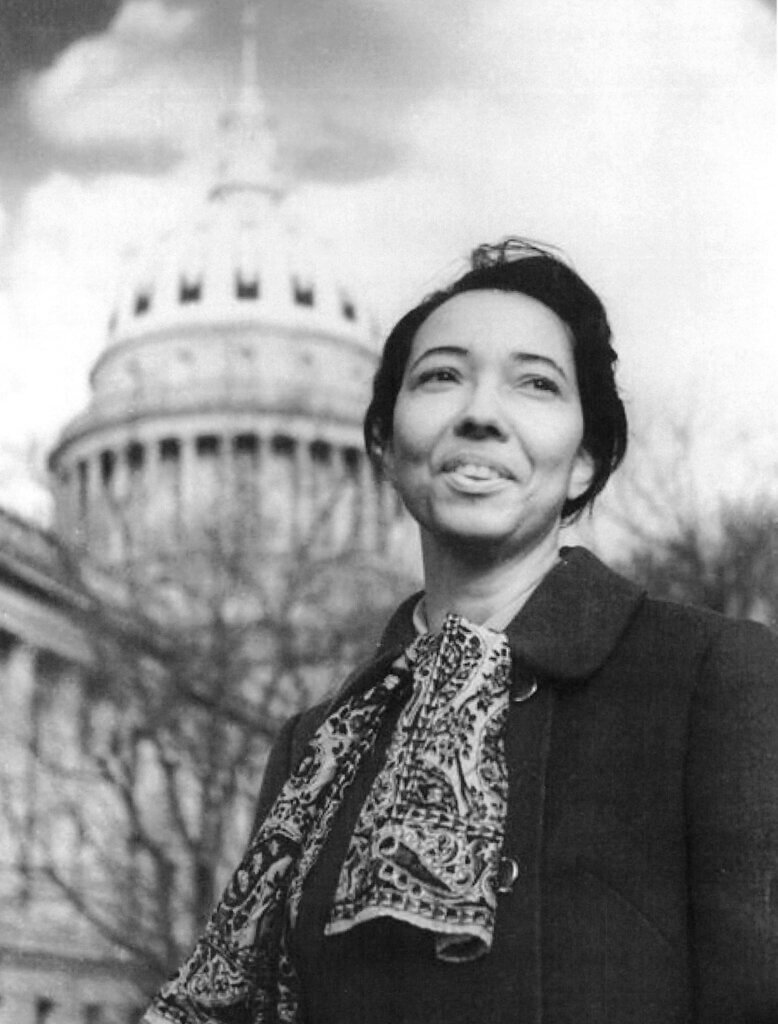

Mildred Mitchell-Bateman

Bringing hope to mental health

Mildred Mitchell-Bateman wanted to be a doctor from the time at age 12, in the mid-’30s, when she volunteered to help survivors of a tornado that tore through her hometown. Although she was preparing for general practice, she felt called by a 1947 opening at Lakin State Hospital near Point Pleasant—the state’s psychiatric hospital for Black patients. Many believed at the time that mental health patients could not be helped, but Dr. Mitchell-Bateman brought fresh hope to her profession.

As she advanced at Lakin—to clinical director, and then, in 1958, to superintendent—she pioneered straightforward new approaches with great success, including pairing the mentally disabled with retirees and integrating patients considered untreatable into the general population. Mitchell-Bateman also raised staff salaries and established a 40-hour work week. She became the first Black woman to lead a West Virginia state agency when she was appointed commissioner of mental health in 1962 and the first Black woman to hold an American Psychiatric Association office when she was elected national vice president in 1973. She was founding chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the Marshall University School of Medicine and served on President Jimmy Carter’s select Commission on Mental Health.

Mitchell-Bateman never stopped advocating for patients, telling The Herald-Dispatch in 2009, in her late 80s, that more funding and attention were needed—including at the hospital in Huntington that, a decade earlier, the state had renamed in her honor. “I’m really hopeful that we can get back on track and get this overcrowding situation solved again,” she said.

West Virginia Teachers

55 strong

On February 17, 2018, thousands of teachers and school service personnel gathered on the steps of the State Capitol in freezing rain, waving signs with slogans like “Will work for insurance” and “If you can read this, thank a teacher.” Many wore red bandanas around their throats. The vast majority were women. It was the beginning of the 2018 West Virginia teacher strike, the historic work stoppage that shut the state’s entire school system down for nine days.

Tensions had been growing for years, but the 2018 legislative session proved a “perfect storm” for union members, Christine Campbell, then-president of American Federation of Teachers’ West Virginia chapter, told WV Living magazine, with legislation in play to undermine public education and weaken unions just as public employees were facing drastic increases to health insurance premiums. On top of that, West Virginia teacher pay consistently ranked among the lowest in the nation.

By the end of the strike, despite opposition from Legislative leadership, teachers got those bills defeated and their pay increased by 5%—and they made lawmakers promise to shore up insurance funding. “It was something I will never forget,” said Jessica Salfia, an English teacher at Spring Mills High in Berkeley County and co-editor of the book 55 Strong: Inside The West Virginia Teachers’ Strike. “It was the power of the collective voice.”

Teachers here inspired similar movements in Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Oklahoma, where it wasn’t uncommon to see teachers carrying signs reading “Don’t make me go West Virginia on you.”

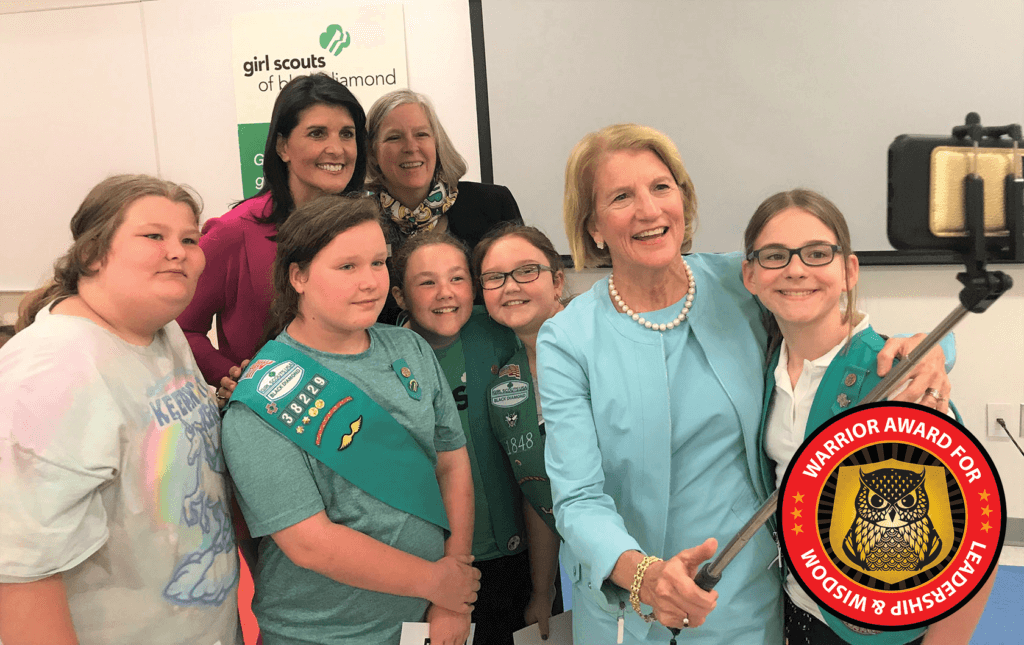

Shelley Moore Capito

A natural role model

West Virginia Senator Shelley Moore Capito didn’t set out to be a trailblazer. But as the daughter of a two-term congressman and three-term governor who has early memories of campaigning for her father, she came to it well-prepared. She stayed home with her kids after college, but, when she felt unsatisfied with what she saw in the public schools, it came naturally to her to run for the state House of Delegates in 1996. And she kept forging opportunities to address problems at higher levels, becoming only the second woman to represent West Virginia in the U.S. House of Representatives in 2000, then the very first female senator from the state in 2014. Capito represents her state as a moderate Republican and, whether you like or dislike her positions, she shows up and she is popular: she won more than 70% of the vote in 2020 and all of the state’s 55 counties.

Senator Capito takes her personal experiences as a daughter, wife, mother, and grandmother to the floor of the Senate. And when she speaks to classrooms, she told WV Focus magazine in 2014, she addresses girls directly. “I have to say to the boys, ‘I’m sorry guys, this isn’t for you.’ And they laugh. And then I say, ‘Come on girls, we’ve got to get busy.’ Because we need more women in the leadership in the political sphere. And I hope maybe some day one of them will say, ‘I remember that lady. I wanted to be like that lady.’”

Read their profiles in our Fall 2022 issue or here as we roll them out online over the next few weeks.

Leave a Reply