What happened to all the talk about year-round school?

It’s not easy, overcoming agrarian roots. But this school year, 2014-15, marks a step along the way. It’s the first year every county school district in the state is required to not only schedule but actually achieve 180 days of instruction—even if making up snow days means continuing well into June.

If you’ve paid only minimal attention to this issue you know that, although school calendars have long been set at 180 days, most districts fall short in most years—that was one of the fundamental findings of the January 2012 “Education Efficiency Audit” of the state’s public school system. State code forced districts to squeeze the whole 180 days, plus another 20 non-instructional days for professional development and other needs, into a 43-week window, according to state code, and weather has usually made that impossible.

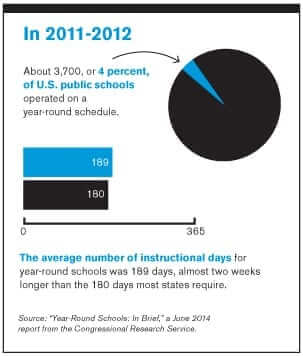

But if we want to raise achievement, enforcing a benchmarked minimum on instructional time is one obvious place to start. Most states require 180 days, and 11 require more, we learned in the audit. European countries mandate at least 190, and Japanese students receive 240 days of instruction.

Lawmakers responded to the audit in 2013 with the gift of new flexibility in school calendars, expanding the window to 48 weeks—along with a mandate to achieve, one way or another, 180 days, starting this school year. An intriguingly named Re-imagining Instructional Time Committee was tasked with helping out. “School districts had to change up their calendars, and they had to have two public meetings,” says Donna Peduto, director of operations for the West Virginia Board of Education. “This committee provided guidance and technical assistance to help them understand their options.”

With the 2014-15 year under way, here’s how calendars shook out. Almost half the state’s districts front-loaded their calendars, with 24 starting in the first half of August this year, four of those in the first full week of August—a month ahead of the after-Labor Day start many of us remember from our own childhoods. School in West Virginia started this year anywhere from August 5 to August 25. A smaller number of districts opted to back-load their calendars, with six extending instruction into the second week of June.

Time Tweaks

But just because true 180-day calendars are now in place, don’t think instructional time has been fully re-imagined. The committee’s work has just moved to a new phase, with lots more ideas to explore. “The thought was, this committee would look outside the box,” Peduto says. “What is instructional time? It’s not necessarily just the time students are sitting in their seats.” The committee considered whether the Internet could make instructional time possible on snow days, for example. Or, if state code were revised to recognize instructional hours rather than instructional days, Internet learning might be used to extend the school day to help students who need to catch up or who want to push ahead of classroom study.

The committee is also looking at incorporating professional development into instructional time—an overlap that, by combining two activities that currently take place at different times, could shorten the school calendar. “Some people call it ‘job-embedded professional development,’” Peduto says. “It requires a creative use of time, but a lot of countries like Finland that have high student achievement have built professional development into the school day.” In line with a recent emphasis on increased district-level autonomy, this could include more local control over the budgets allotted to professional development, she says, as well as over content, “rather than 500 teachers coming to Charleston and learning the same thing.”

And a primary theme of the Re-imagining Time Committee’s future work is to showcase best practices with regard to the use of time. One school might work out a schedule on which everyone does planning on the same day each week, Peduto says, and other schools might like to know how that was done. “We met with a legislative subcommittee last year that said there are great things going on that nobody knows about,” she says. “There are a lot of pockets of innovation.”

The Bugaboo

No one can imagine re-imagining instructional time without considering the perennial object of angst and avoidance: year-round school. Also known less inflammatorily as the balanced calendar, it’s very much on the Re-Imagining Time Committee’s radar.

The flip side of the short school year—a long summer break—has been found to result in academic backsliding. It especially hurts students from low-income backgrounds, where the family environment often provides less enrichment. Peduto eagerly shares a YouTube video of a 2011 NBC spot showing cumulative summer losses that put low-income students years behind middle-income students by the end of elementary school. A state Department of Education web page promotes a balanced calendar that addresses this by redistributing the long summer break into shorter, more frequent breaks throughout the year—for example, four cycles of nine weeks on, three weeks off, with a slightly longer summer break.

Opponents of the balanced calendar don’t only lament the loss of the true summer off. Other arguments include insufficient air conditioning at some schools and the sports and other extramural scheduling conflicts that would result with schools that don’t change to balanced calendars. Proponents point to minimizing summer learning loss and better consistency in nutrition for lowest-income children, as well as to the opportunities intersessions pose for lagging students to catch up and for camps and other learning enhancements.

Just two schools in the state so far, both of them elementary schools in Kanawha County, operate with balanced calendars. “People at those schools like the consistency of the instruction,” Peduto says. While the state Board of Education is so far emphasizing local decision-making about calendars, it’s likely that it will also continue to publicize the advantages of year-round school. “Nationwide, I don’t know if I’d call the balanced calendar a trend,” Peduto says. “But there’s more and more research saying it’s really a good thing.”

Written by Pam Kasey

Leave a Reply