We’re off and running, but there’s a long road ahead.

Community development work isn’t easy. There’s a lot of waiting around for projects to get approved, for money to come in, for people to get on board. A lot of it is dependent on things that are at least partly outside of your control: Will we get approval? Will we get that grant? Is it too expensive? Is it impossible? “Community development is hard work,” says Kent Spellman, the West Virginia Community Development Hub’s executive director. “But that’s what makes it worth doing.”

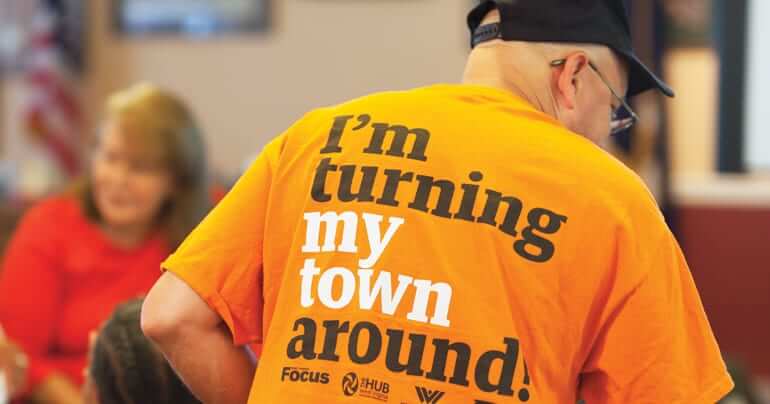

Our Turn This Town Around initiative has been alive in Grafton and Matewan for more than six months now, and we’re happy to say that progress has been made. There have been town cleanups and community meetings. People have volunteered for planning sessions and construction projects, to paint things and clean things and write proposals for things. Money from outside of Turn This Town Around has already started trickling in—at least partly the result of all of the momentum surrounding this project. And more money is on its way—Turn This Town Around mini-grant proposals were submitted August 1, 2014, and grantees were announced in each community the second week of September. But now comes the part where these projects stop being something people talk about and become something people do.

Our resident community development experts, the team at the Hub, like to say that part of the beauty of projects like Turn This Town Around is they force accountability because they force you to go public. You can’t just quietly toil away on a pet project for years and years—or quietly quit working on it—because you’ve told people about it. And once you tell people you’re going to do something, there comes a time later when you have to tell them one of two things: Yes, I got it done. Or: No, I didn’t.

Grafton’s Manos Theater

The Manos Theater sits on Main Street in Grafton, a remnant of a livelier downtown. It’s not stately or grand, exactly—it’s a humbler breed of historic theater, with a rough stone facade on the ground level and a blank cement face on the second floor. Built in 1949, the Manos was, like so many theaters in the mid-20th century, at the heart of the town for years, but gradually fell into disrepair.

Community members who are interested in revitalizing Grafton have been eyeing it for years—old theaters like the Manos are important, often iconic, elements of a downtown’s infrastructure, rife with potential if only they were operational. “Theater experiences are memorable, so we hope people will want to come downtown to go to the theater, then want to come back to make traditions,” says Gigi Collett. “And I think one important element is trying to connect the dots, using the theater to help make Grafton as a whole an experience for anyone who wants to come to town or who lives here now.” Collett is part of a team of people who are working on renovating and restoring the Manos. She’s well positioned for this because she’s on the board of Grafton’s International Mother’s Day Shrine, which owns the theater. Plus she has a theater background and is as passionate about the arts as she is about Grafton’s future—you can hear the fervor in her voice when discussing either—which can only help the cause.

The Mother’s Day Shrine bought the theater around 15 years ago with the help of the city and the state, with the aim of restoring it, opening it to the public, and using it to generate money for the shrine across the street. They began working on renovations with grants worth around $25,000—the Manos got a sound and lighting upgrade, the stage was extended some seven feet, renovations were made to the lobby, and an accessible bathroom was installed—but there’s still a lot more to do. “It was a good upgrade,” Collett says. “But we still can’t use it to its full potential, not even close.” Collett and her team are applying for three Turn This Town Around mini-grants to help the Manos, each built around a different goal that will improve the theater and, they hope, draw people to it—and by extension, to downtown Grafton. “We want everything to have a symbiotic element, like we’re all connected, we can all help each other,” Collett says.

The first of these projects is for the movies themselves. For years people in Grafton have been talking about movie screenings at the Manos—the idea has come up again and again in the Hub’s community meetings. What no one quite understands is how expensive an undertaking that is. Buying the license to show a movie—even a bad movie, a B movie, or an old movie—costs a lot of money, usually around $300. Collett and the the team at the Mother’s Day Shrine would show movies at the Manos every day if they could—but they can’t afford it. So they’re applying for a mini-grant to get started. The idea is to use the $2,500 in grant money to start a movie licensing fund for the theater. They’ll use the money to show movies regularly for a while, charging a minimal fee for those viewings that they hope will generate money for more movies. Think of the grant as seed money that could grow into a regular schedule of movie showings at the Manos for years to come.

The second mini-grant would help the team repair the theater’s heating and cooling system—it’s been broken for years, leaving the theater unusable in the winter months. “We’re still getting into the bones of the building and seeing what needs to be done,” Collett says. No one is quite sure what happened to it, but they all agree that its repair is critical if the Manos is going to be a viable business again. Over the summer the Manos saw at least a trickle of activity: The city purchased a few movies and showed them there, an amateur theater company from Clarksburg brought an improv comedy show to the Manos, and then a modern rendering of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. There was even a short opera. But without a working HVAC system, all of that activity will be forced to a halt when winter arrives. Collett says a $2,500 mini grant should at least put a sizable dent in the cost of the heating and cooling project. “We think all of our projects are going to need extended money, but we are hoping that once we get the ball rolling and people are actively engaging in that space and seeing the benefits of it we can get some additional money from the community,” she says.

The third mini-grant would let the team at the Manos install a simple concession stand, complete with a popcorn machine—they hope to use concessions to generate more money for the theater moving forward. In the long-term, the Mother’s Day Shrine hopes to found a children’s theater company at the Manos that would give Grafton’s children a creative outlet and keep them invested in the Manos and their downtown. “Athletics have been the cornerstone of this community for so long,” Collett says. “And there’s nothing wrong with that, but some kids don’t excel at athletics. This is just a different way to build skills in kids who might not want to hit a ball out of the park or throw a touchdown pass. And it’s right in the center of town, in the center of the county, so it’s a perfect spot to draw kids in.”

Bike Friendly Matewan

The people in Matewan are intent on building an economy around tourism, taking advantage of the little town’s railroad and coal mining history and its place in the storied feud between the Hatfield and McCoy families. So a lot of people in Matewan are working on projects with a tourism bent, from geocaching courses to historic plays to walking tours. Kelly Webb, who is heading up a project to make Matewan bike friendly, wanted to come at the tourism thing from a slightly different angle. She says she was just being pragmatic—she wanted to bring in as much money for her project as she could and figured it couldn’t hurt to diversify a little. “In this county they’re on a health movement, and I thought choosing a project that would incorporate that might give me an opportunity for some great additional grants,” she says.

She started researching healthy lifestyle activities that could also draw in tourists and stumbled onto the bicycle tourism industry. “There are so many bicycle enthusiasts across America, and they bike to all these places across the country all summer,” Webb says. “The majority of towns they travel to, they’re not big cities, and they want to go see things, like historic places. So sometimes these really rural communities make themselves bike friendly neighborhoods, and they work really well. There’s a huge market for bicycle enthusiasts and people want to ride bikes in this area because of the mountains.” It felt to Webb like a perfect fit for Matewan.

Webb and the rest of the group working on Bike Friendly Matewan have a long list of projects they think will come together to make the town appealing to bicyclists across the country and encourage locals to take to bikes as well. They want to create a bike path running through downtown Matewan and into the outskirts of town, implement a bike safety course, create a system to keep the routes clean and appealing all the time, print up some brochures to advertise and promote the whole thing, and eventually get certified as a bike friendly community by the League of American Bicyclists. At some point they’d like to link Matewan’s bike trails to the Hatfield & McCoy ATV & UTV Trails—mountain biking is permitted on them as well—but that’s more of a long-term goal. “Right now we’re going to focus on the things we can make progress on immediately,” Webb says. Bike Friendly Matewan has already brought in some money from outside of Turn This Town Around, being awarded $3,000 from the Try This mini-grant program, and submitted applications for a handful more. Webb is optimistic, and hopes to hold a ribbon-cutting ceremony next summer.

That Said…

Of those 57 grant proposals submitted to the Hub, a few of them weren’t awarded funding. The Hub will be working with those groups to see if there is another way for them to make their projects happen. In Matewan, the tiny town was able to come together to form groups around 15 different ideas, but they still left some money that could have been claimed through mini-grants on the table. It’s not over yet—community members will be able to submit new mini-grant proposals for new projects later on, and we hope to eventually find enough projects to spend all that money from The Benedum Foundation. And as Mary Hunt, a senior program officer with the foundation, says, success in community development can be measured in myriad ways. “I think one success would be that at the end of this we have 20 completed, tangible projects,” she says. “But I think the project is also a success if it helps frame a more positive community image, if it grows into wider community involvement and a sense of more positive possibilities within the community.”

Leave a Reply