The only freestanding early Morgan home left in the Monongahela River valley came within inches of demolition in the 1980s–and it has the cracked front steps to prove it.

When David and Sarah Morgan moved their family west in the early 1770s from the Upper Potomac to the Monongahela River valley, they staked out a rise in a broad, squarish loop in the river. It was raw, untamed wilderness. But David and his younger brother Zackquill, two of the earliest settlers in the valley, could handle wilderness—they were sons of Morgan and Catherine Morgan, the very first Europeans to homestead permanently in western Virginia.

David cut trees and built his family’s cabin smack in the middle of that loop in the Mon, with the river less than a mile to the northeast, southeast, and southwest. Then, a mile straight south, across the river, he and Jacob Prickett built Prickett’s Fort in 1774 as protection from natives. Once during a period of hostilities, David left the fort suddenly on a premonition and ended up killing two natives to protect his children—earning the 60-year-old the admiring nickname “Indian Fighter.” Natives burned their cabin in retaliation. David and Sarah moved a few miles upriver to land he owned at present-day Fairmont and, when Sarah died in 1799, David floated downriver with her body on a raft. He took her to the site of their earlier cabin, carved a headstone for her, and, with that, started the family cemetery.

David cut trees and built his family’s cabin smack in the middle of that loop in the Mon, with the river less than a mile to the northeast, southeast, and southwest. Then, a mile straight south, across the river, he and Jacob Prickett built Prickett’s Fort in 1774 as protection from natives. Once during a period of hostilities, David left the fort suddenly on a premonition and ended up killing two natives to protect his children—earning the 60-year-old the admiring nickname “Indian Fighter.” Natives burned their cabin in retaliation. David and Sarah moved a few miles upriver to land he owned at present-day Fairmont and, when Sarah died in 1799, David floated downriver with her body on a raft. He took her to the site of their earlier cabin, carved a headstone for her, and, with that, started the family cemetery.

Those early settlers were real frontierfolk. The 1768 treaty that pushed the Iroquois across the Ohio River didn’t make the Mon safe right away, but eager pioneers started planting their lives beside the wide, shallow river anyway. David and Zackquill among them are local legend today—David in Marion County and Zackquill in Monongalia. Many of the stories are hard to confirm, but the men’s clear hand in the region’s future seems to justify them.

The brothers fought under George Washington in the 1755 and 1758 expeditions to take Fort Duquesne, at today’s Pittsburgh, from the French.

David and his family planted crops and orchards at their farm on the Mon, and the Morgans contributed energetically to civic life. David surveyed the town of Pleasantville—today’s Rivesville—and Zackquill laid out Morgan’s Town 20 miles downriver. Cousin Daniel Boone rode through from time to time. Come 1777, the brothers fought as patriots, as did four of David’s boys. And when they weren’t fighting natives, or the French, or the British, Morgans served in critical peacemaking roles like sheriff. Their descendants include William S. Morgan, a botanist and Virginia congressman who carved out Marion County, and Francis H. Pierpont—the Father of West Virginia.

So in 1987, when locals challenged a bulldozer at the threshold of the only freestanding early Morgan home left in the Mon valley, they took that personal risk in remembrance of a proud legacy. Childhood neighbor Jim Rote has since returned home to West Virginia and bought and restored the home as a private residence.

History Worth a Risk

The house is thought to date to the 1850s. George Pinkney Morgan built his family’s two-story, ell-shaped, red brick home on the piece of land that

George is said to have been a good farmer. And when the B&O rail line came through Fairmont in 1852, he assembled investors in the Marion Cannel Coal Company to mine coal on the property and constructed a spur line to connect with the B&O. Maybe it was coal income that built his home, which was large and fancy for that place and time.

George was a Confederate like many of his relatives. But as was true for so many, the family was deeply divided. He was captured in a skirmish at the October 1861 Battle of Greenbrier River, even as his cousin Francis Pierpont had come to head up the pro-Union Restored Government of Virginia. George died a Union prisoner, not yet 40 years old. His widow, Catherine, and their children lived together and farmed the land for the rest of their lives. They took a foster child, Walter Curnutte, into the family in the early 1900s; he eventually inherited the place and farmed it on his own and then arranged for it to be strip mined. When he died in 1975, the house had been occupied essentially by one family for more than a century, with little modification.

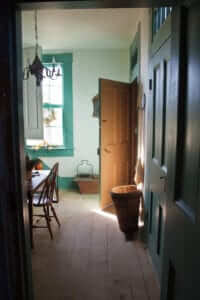

Rote had grown up across the street in the 1950s and ’60s. “Walter had ponds on the property. I always liked his house,” he says. “I remember herds of cattle, big fields of corn, and all the fruit, and down along the driveway there was probably a 200-yard-long truck garden.” But when he went inside the house after the injunction, it looked terrible. “It took about a day to cut all the briars just so we could get in. It sat unlocked with the window sashes lying on the floor, and there was probably a foot and a half of trash on the floors,” he says. Someone had dismantled the curved banister—to remove a mattress, by one account, and possibly burned by intruders for warmth—and the parlor mantelpiece lay on the floor, detached from the wall but apparently too heavy for plunderers to carry off.

Rote bought the house in 2000. Built solid, the 150-year-old structure had survived maltreatment and near-demolition in remarkable shape. Rote once worked at the Colonial Williamsburg living history museum and has a fondness for old properties, and he began a thoughtful restoration.

Original Materials, Historical Details

To the right, “there’s a beautiful stairway,” he says. “It goes up to a landing and curves back around, and it’s a semi-flying staircase—there’s no wall underneath to support it.” Rote found a banister at a colonial salvage shop in Richmond, Virginia, that perfectly replaces the original. Details add lightness and grace. “Features of note in the hall are the scroll-sawn wooden appliqué edging on the stair treads,” reads the 2003 National Register of Historic Places nomination.

In the parlor, to the left of the entry, that heavy mantelpiece took four people to put back in place. It’s an attention-getter. “Strong, squat columns support a very large, simply carved mantel that resembles an open book,” reads the National Register nomination. The Morgans must have loved hosting: A three-hinged-door-wide opening made it easy to connect the parlor with the already immense dining room beyond for large gatherings. “The dining room is 30 feet long, which was probably the length of most houses in that time period,” Rote says. To the left, the “foot” of the ell holds the servant’s prep room, and a pass-through in a built-in cabinet between the two rooms kept servants efficient and unobtrusive. Upstairs, six bedrooms surround the open side porch that hunters used to use. Bedrooms still have their original millwork, and two have fireplaces.

While renovating, Rote and fiancée Mary Kaufman stripped as many as 15 layers of wallpaper. “She was able in some rooms to find the very first layers, and those were hand block-printed wallpapers,” Rote says. “She laminated one set so we can show them to people, and we preserved another set in archival paper.” Rote’s period furnishings and window and door hardware, along with decorative and functional ironwork, complete the 19th-century feel.

Christmas at Morgan House

Rote brings a historical sensibility to his holiday decorations. “A lot of candles, pine, magnolia branches,” he says. Bittersweet wreaths, too. “They grew

Rote receives visitors by appointment. Also to be seen on the property are the family cemetery of 20-some family graves and, nearby, a 14-foot stone monument erected to David Morgan in 1899 “directly upon the ground of his famous encounter with two Indians.”

“We always think the interesting history happens somewhere else,” Rote says. “But from the mid-1700s, there was a lot going on here.” jimrote@hotmail.com

Leave a Reply