Jacob’s Ladder recovery farm in Preston County overcomes the instant gratification of drugs through experience with slower satisfactions.

Tim struggles with addiction. Alcohol, mainly, but also cocaine, heroin, and whatever’s available. But he’s motivated: He wants to get custody of his two young daughters.

He finished a successful six months at the Jacob’s Ladder recovery farm in Preston County in 2016. Eager to be

“He busted his butt without a car, walking, putting in applications, trying to get a job, but he’s got a felony record so no one would hire him,” says Jacob’s Ladder founder and CEO Dr. Kevin Blankenship. Not surprisingly, Tim—not his real name—fell into depression and ended up using again. Blankenship invited him to return to the farm

As one of Jacob’s Ladder’s “failures”—you can hear the air quotes in Blankenship’s voice—Tim is helping to refine this pioneering treatment program’s understanding of what works and what doesn’t.

Rethinking treatment

A West Virginian by birth and an emergency medical doctor by training, Blankenship was a co-founder in 2001 of the enormously successful Morgantown-based urgent care chain MedExpress. He served as its chief operating officer until he left there in 2009. But his life took a turn when a brother-in-law died from alcohol and opiate abuse earlier this decade and then his own son struggled with addiction.

“People are dying and they need help, and I don’t think we’ve completely figured out how to help them,” he says. “I had to step back and figure out what I wanted to do to effect change, not only for my son but for everyone else who’s out there struggling. And for West Virginia.”

He spent more than a year reading everything he could about addiction, going to conferences, listening to the best minds on the topic—looking for a way to flip the state from the leader in overdose deaths to the leader in a compassionate and effective solution.

His son’s experience at the six-month Back2Basics Outdoor Adventure Recovery program in Flagstaff, Arizona, influenced Blankenship’s thinking. “I felt strongly that we needed to be a six-month program, because I saw it work for him.”

Recent brain science influenced his thinking, too. “Only maybe 20 years ago, the medical community was convinced that you’re born with so many brain cells and you can never improve upon that,” he says. But neuroplasticity research showed him that, not only can people form new brain cells, they can form millions of new brain cell connections. “These guys, when they’re using, they’re used to living in the moment, making decisions that affect the next couple hours of their lives. Their futures—job, school, work, family—their brains don’t work that way anymore.” He came to think that people who have gotten trapped in addiction could lay down new neural pathways through the lived experience of investing in the future and garnering the eventual reward—an experience farmers live hands-on. “Plant something today, reap the benefits in a couple months. Raise this animal, slaughter it in a couple years. If we can combine that type of thinking with the appropriate amount of time away from their other activities, we can make a difference.”

He opened Jacob’s Ladder in April 2016 as a six-month recovery farm unlike any other long-term treatment facility in the state, or possibly anywhere. There are beds for 14 men and about a dozen staff, more than half of whom are well into their own recoveries and have been trained in peer recovery coaching.

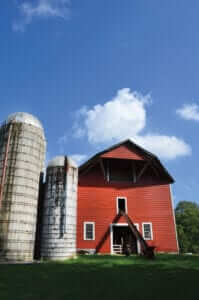

The setting—the turn-of-the-20th-century Brookside Inn resort at Aurora in Preston County, now an expansive family farm that partners with and leases facilities to Jacob’s Ladder—works as a peaceful retreat a little over an hour’s drive from Buckhannon, Clarksburg, Morgantown, and Cumberland, Maryland.

Learning to live life again

The daily routine at Jacob’s Ladder focuses on mindfulness and everyday tasks. Residents start their weekdays

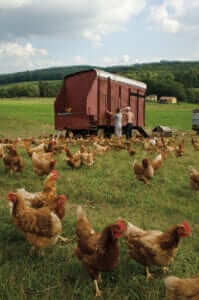

Afterward the men work on the farm, tending leafy rows of everything from tomatoes to sweet potatoes to watermelon, weeding the rich soil by hand. They care for 300 chickens as well as sheep, pigs, and beefalo. “They’re getting their hands dirty, planting seeds, pulling up weeds, and then when they get the vegetable and they’re cutting it up in the kitchen, they can appreciate it,” Ferguson says. They devote time to music, art, and reading, and prepare meals together, with lunch served at noon and dinner in the early evening. Days are simple and ordered. “A lot of these guys are 18 to 25—their addiction grabbed hold of them in their teen years. You get clean and have to learn how to live life again.”

At least four evenings a week, the men are bussed after dinner to 12-step meetings in Clarksburg, Morgantown, and other surrounding towns—both for the fellowship and to experience as many recovery communities as possible. Then it’s lights out at 10:30, with a more relaxed schedule on weekends. Several times a month they travel as a group on outdoor adventures. “We were whitewater rafting as a team-building exercise the day of the solar eclipse,” Ferguson says. “When the eclipse was happening, we got to kick back and watch. A lot of these guys have never done anything like that.”

A year-plus in operation in the summer of 2017, Jacob’s Ladder had graduated 16 men, two of whom had relapsed, including Tim. “I was heartbroken rather than surprised,” Blankenship says. Both had chosen to return directly to their home communities. “What I learned more than anything is that these guys can’t go back where they came from immediately.”

Meeting the need

Although it’s operating in the state with the highest overdose rate in the nation, Jacob’s Ladder is not as overwhelmed with applicants as one might expect. “Even if we say, ‘Come on in, we’re here for you,’ nine times out of

10 that person doesn’t come,” Blankenship says. “It’s so much more real than, ‘OK Mom, I’ll do a 30-day program to get you off my back.’ For someone struggling with addiction, a six-month commitment is a lifetime.”

There’s also the question of money. In order to continue working nimbly with residents, Jacob’s Ladder doesn’t take health insurance. It asks families to pay and makes some allowance for financial circumstances. Ferguson continually works to expand his referral network for those who apply but aren’t a good fit.

But for those who are a good fit and are ready to make that commitment, no place sounds better. “A young man contacted us from prison about eight months ago and said he needed to find a program,” Blankenship recalls. Jacob’s Ladder didn’t have a bed available at the moment and, although the prison would have released him to any treatment facility, he held out. “He stayed in prison an additional month and a half waiting for a bed to open in our program. He graduates next weekend and he’s a wonderful young man. That’s the kind of commitment we see in the men who choose to come here.”

Another reason Blankenship liked a farm model for his program is that, since it leverages West Virginia’s assets,

One of the biggest lessons Blankenship has taken from this experience gives hope for the future of West Virginia, once the state turns this crisis around. “The best people I’ve met in my life I’ve met in the past couple years, people who are recovering,” he says. “Because to get to that point, you have to dig down deep and examine yourself way more closely than you or I have done. They’re some of the most enlightened, humble, appreciative people you’ll ever meet, and all they want to do is live good lives and help other people live good lives.” jacobsladderbrookside.com

Photographed by Nikki Bowman

Leave a Reply