West Virginia’s small towns find creative ways to grapple with a growing problem of food insecurity.

Fifteen miles on an interstate is a lot different from 15 miles in the middle of Clay or Boone county. A 10-minute drive in larger towns takes you past amenities that require a 30-minute drive out of smaller ones. In 10 minutes, ice cream softens but doesn’t melt. In 10 minutes, frozen chicken forms ice crystals but doesn’t thaw. In 30 minutes, ice cream is a swampy mess and meat gives way at the press of a finger like the flesh of a parent’s arm pulled by a hungry child anxious for lunch. When a grocer is 10 minutes away, you huff at the inconvenience of running back to the store mid-week for the much-needed green beans your spouse forgot to purchase during the weekend shopping trip. When the grocer is 30 minutes away, you do without.

In West Virginia—rural, green, growing West Virginia—more and more people are doing without. The stories fill newspapers. In 2014 Bridgeport lost its last grocery store; Kroger stores in Kanawha and Lewis counties closed; Alderson lost its last store; the Richwood Foodland closed its doors for the last time; and the Whitesville Save A Lot, the only grocery store serving the community for 15 miles, also shuttered. The trend has continued in 2015. In April St. Marys in Pleasants County lost a food store to a fire. In May Clay County’s last grocer, a Piggly Wiggly, pulled out of the area.

But growing in place of these grocers, in small towns with small populations, are innovative social enterprises dependent on big community. Bridging the gap between relatively high-end local food movements like farmers’ markets and lower-end income-based food pantries and services, these organizations are pioneering an effort to feed the state. It’s an effort that’s more about people than about profit.

Growth of a Nutritional Wasteland

When Clay County’s Piggly Wiggly closed, it left the community reeling. Few understood why the only store in an entire county would shutter. The nearest option now is in Flatwoods, 46 miles one way. “There were always a lot of my patients who had the ability and resources to drive the 45 minutes to an hour to a bigger store in a surrounding county, but a significant portion didn’t and aren’t doing that,” says Kimberly Becher, a family medicine physician working at Community Care of West Virginia in Clay. “A lot of my patients walk wherever they need to go, which means now, instead of a grocery store, they buy food at GoMart.” Or at the Family Dollar downtown.

Imagine a cookout provisioned by food purchased at a GoMart or Family Dollar. The staples of a summer barbeque—corn on the cob and watermelon, or burgers topped with juicy ripe tomatoes and crisp lettuce—are nowhere to be found. “My patients complain that not only are their choices significantly limited, but shelves are sometimes empty because the bulk of the town and county are shopping in stores not intended to supply a community with three meals a day,” Becher says.

In Whitesville, where the community lost its Save A Lot nearly a year ago, the story is much the same. “At one time we probably had three or four grocery stores,” says Sue Pauley, an outreach coordinator for the Whitesville food pantry run by Catholic Charities in town. “Everybody just shopped everywhere—go here, go there, follow the sales.” By Pauley’s estimates the town’s stock of stores dwindled to just a Foodland a decade ago, which later became the Save A Lot. Most say it wasn’t a quality store, but it was something. “It had milk, it had bread, cheese—staples that people need,” Pauley says. “It has hurt us, not having grocery stores.” Seniors like those living at the Mountain Terrace senior apartment building in Whitesville are especially vulnerable. “They would shop at the Family Dollar, but we lost our Family Dollar. Now there’s a bus that comes through once a week and it takes them to Walmart.” A Dollar General sitting just outside town is all that’s left now. Signs on the door often read “No milk,” “No bread,” or “No water.”

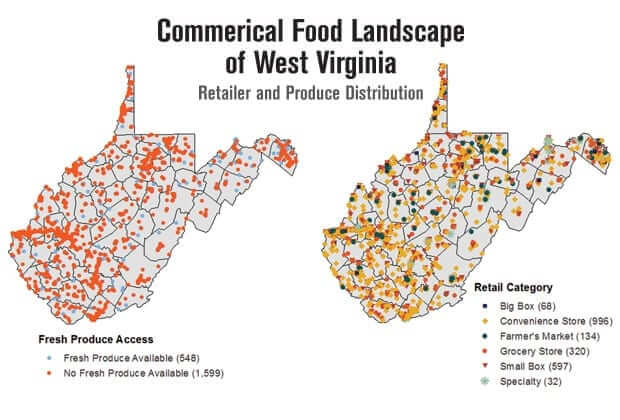

There’s a term for places like these: food deserts—loosely defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as urban neighborhoods and rural towns without ready access to fresh, healthy, and affordable food. “It’s a question of deprivation caused by lack of access to nutritious foods or the money to purchase nutritious foods,” says Bradley Wilson, director of West Virginia University’s FOODLINK, a program studying sustainable, community-based food systems across the state. “Food-insecure families are everywhere,” he says. “And food insecurity—hunger—has a particular face in rural areas that it doesn’t have in urban areas.”

National statistics compiled by the USDA show that more than 23 million Americans live in both urban and rural places officially designated food deserts. In these areas, issues like obesity and diabetes are only exacerbated by limited access to healthy, fresh food and easier access to pre-packaged, sodium- and sugar-heavy products like those that line gas station shelves. Food deserts are even found in areas traditionally considered wealthy.

“Monongalia County is seen as the shining star of West Virginia,” Wilson says. “It has all these excellent employment opportunities. There’s economic growth. There’s 5 percent unemployment, even during the period of the financial crisis. But there’s still a Census estimate of 22 percent of the population living below the poverty line, and there’s roughly 14,000 people a month who are served by food assistantship agencies—and that’s a low estimate.” Twenty-six percent of the population in Monongalia County has low access to a grocery store, according to 2010 USDA figures, the latest available. Nearly 10 percent are affected by both low access and low income.

Well-off or poor, urban or rural, families adapt or they suffer. Hollie Smarr, a pharmacist in Whitesville who recently welcomed her first child, says her family does a lot of weekly meal planning to limit travel for shopping. “When we go to our church in Teays Valley we might go to Kroger in Charleston,” she says. “We plan ahead. If we have some place to stop, any family to visit while in Charleston, we normally take coolers. But it’s just the convenience of a local grocer that we really, really miss. I don’t think you realize until it’s gone how much you’ll miss it.”

At best, that struggle means an hour’s drive to and from Kroger once a week, filling an extra freezer in the basement, and planning meals a month in advance. At worst, for families and senior citizens that haven’t the means or ability to drive to the store, it means depending on neighbors for a ride or simply going without. “Families are looking at their entire economic puzzle, and they’re like, ‘This month I can put these together, but there’s a hole.’ And food does end up being the hole very often,” Wilson says.

Desertification

The explanations for the grocer closings are almost always the same. “It comes down to bare business,” says Chon Thomlin, corporate spokesperson for Save A Lot, a discount grocery chain owned by Supervalu. In May Save A Lot opened a new store in Elkins, months after closing its Milton distribution warehouse that employed dozens of people. “We don’t pull out of a market without making sure a store can perform or is performing the way it should,” Thomlin says.

But Wilson would argue the roots of food insecurity go much deeper than that. “It’s important to think about the evolution of food deserts in a historical context of how people got access to food, period,” he says. “Whether it was through gardening for themselves, through farming, through grocery stores that developed in particular areas, or government subsidies and provisioning of food in particular times and places. I don’t think that food deserts are something new at all. Hunger has always been a big issue in the United States.” Our current food desert problem—one that on the USDA food environment map has nearly two-thirds of the United States highlighted in orange and red—Wilson says is linked to the growth of a nationwide food system around since the 1950s. “It’s retail consolidation that’s happened,” he says.

The Whitesville of 50 years ago, like many West Virginia towns, isn’t the Whitesville people know today. The three or four independent local grocers Sue Pauley remembers were stocked by independent wholesalers who aggregated product from around the country—fruit from California, corn from the Great Plains, meat from Chicago or Cincinnati, cloth from the Carolinas, the list goes on. “Those regional suppliers are increasingly linked up into retail consolidation,” Wilson says. “The brokers who are purchasing large volumes, who then distribute to local grocers, are also competing within a vertically integrated supply chain— from farm to you in the supermarket—that’s managed by Kroger or through a Giant Eagle or through a Wegmans or a Whole Foods.”

Over the past few decades, large supermarket chains have increasingly outcompeted the local grocers, to the point smaller stores can no longer stay in business. Sales by the nation’s 20 largest food retailers—led by Walmart and Kroger—totaled $449 billion in 2013 and accounted for 64 percent of U.S. grocery sales, according to the USDA. In 1993 those 20 big names accounted for 40 percent of U.S. grocery sales.

“The disappearance of local grocery stores is not because local grocery stores are just throwing in the towel,” Wilson says. They are unable to compete with the Krogers, with the Walmarts, and with those last-standing Family Dollars and Dollar Generals upon which rural West Virginia increasingly relies. According to FOODLINK research, small- and big-box retailers like Walmart and dollar stores outnumber grocers in West Virginia two to one. “A grocery store can’t just be vegetables,” Wilson says, adding that dry goods like toilet paper and paper towels are integral to a grocer’s inventory. “They have to sell all this stuff to make up their overhead, and when they’re competing against the small-box retailer that rolls into town, like a Dollar General, they are competing against their toilet paper prices. And when people go to them for their toilet paper price, the grocery store disappears.”

The disappearance of small-town grocers is depressing for local townscapes left empty at their retreat and for townsfolk who fondly remember the good old days. But the disappearance becomes disastrous when the box stores later pull out on their own accord, leaving people with nothing. Walmarts have given way to Walmart Supercenters and Kmarts to “big” and “super” versions, and Krogers to even fancier, more decadent stores. Kroger claims it invested $32 million in West Virginia for improving 12 stores from 2010 to 2014. During that time it has also closed at least two stores in the state, one in Weston and one in Quincy. “Kroger has limited opportunities to build new stores in West Virginia because the state’s population is not growing,” says spokeswoman Allison McGee. “The size of today’s Kroger stores is larger, making it more difficult to justify building in smaller communities.“

The company’s focus instead, she says, has been on improving existing stores. Meanwhile in Weston, where 3,000 people joined a “Save the Weston Kroger” Facebook page and where the former Kroger has sat empty for more than a year, folks are driving to another county just to buy bread.

Where New Seeds Are Being Planted

In the wake of these closings, however, new enterprises are taking root. These stores are a mix of ingenuity, necessity, and altruism, opening to fill the nutritional void of communities left without traditional grocers. Some are accompanied by headlines heralding their success, and others are chugging along in relative anonymity, known only by the communities they serve.

In Alderson, a town whose identity revolves around summer and the seasonal influx of visitors coming to camp on the Greenbrier River, the loss of the locally owned IGA store in 2014 was a big blow. “The fact that we could no longer say we have a grocery store in our community—but ‘Come visit us!’—was a big deal. As soon as IGA announced they were closing, people had to respond immediately, because they need food,” says Kevin Johnson, board president of the Alderson Community Food Hub. “The general sense was, ‘Is this a bellwether for the future of the town?’” Johnson says residents were increasingly reliant on nearby centers like Lewisburg and Beckley for jobs and shopping. But when IGA closed, the town rallied. “People love their town. I love Alderson, and there’s a hope that by keeping the bone structure of Alderson alive there will be a future.”

The food hub, which had already started as a community market in 2010, had grown to include an educational program, a community garden, and a co-op. “But I would be lying if I had told you that opening a full grocery store was in anyone’s mind before a year ago,” Johnson says. Yet that’s just what the town did. Alderson raised more than $30,000, volunteers spent hours painting and prepping the space, and the Alderson Green Grocer launched in April, just months after the IGA closed.

On the first day of business, the store was jam-packed. “It was amazing to see all the pent-up demand,” Johnson says. Opening day had been rushed. The group finished its fundraising campaign only weeks before. Volunteers were still painting. “We were not full, by any means, with our inventory. But we were slammed the first day with people coming in and looking around. I think we did $1,700 that day.” The point of the Alderson Green Grocer isn’t to make money, although the store does have goals to meet its costs. The point is to fill a need. “Earlier in the year it had come up that there were four places in town that sold pet food and six that sold motor oil. But there were no places to buy a potato or an apple or anything like that. I think people understand that’s a fundamental need here,” Johnson says.

Alderson isn’t an isolated phenomenon. In Philippi, Heart and Hand House is celebrating 23 years of its Barbour County Community Garden Market—a place where professional and nonprofessional growers can consign excess garden produce, baked goods, and even jams and honey. Growers receive 80 percent of sales and leftover food goes to stock the Heart and Hand House food pantry, while the remaining 20 percent of profits help cover the costs of running the market. “The 20 percent doesn’t cover all our costs, but we feel this has been a service for the community for many years,” says executive director Brenda Hunt. There are now only two retail grocery stores in Barbour County, Shop ’n Saves in Belington and Philippi. “Other than that, folks have to go to mom-and-pop corner shops. Most people have to travel to Elkins or Buckhannon.” Either town is a half-hour drive one way.

In Philippi the Community Garden Market isn’t just a nutritional opportunity, it’s an economic and social one as well. “Not only are we in a food desert, but there aren’t a lot of employment opportunities either. We’ve had participant growers say they use that money to supplement heating costs,” Hunt says. The market began accepting SNAP benefits years ago, but its customer range is broad, spanning college students, the local workforce, and curious travelers who take an opportunity for a rest stop. “It’s always been a gathering place that people love. We see it on several fronts being a benefit to the community.”

The Heart and Hand House Community Garden Market was one of the first consignment model markets in the state. Recently, it’s been joined by the Wild Ramp in Huntington, an organization largely run by more than 200 volunteers sourcing food from 170 food producers and artisans. Also in Huntington, local kids are learning to garden and sell their produce to local businesses and restaurants with the SCRATCH Project.

Five Loaves & Two Fishes Food in McDowell County is a food bank supplied by hydroponics gardens. In its long-term plan, the organization is looking to add a produce stand and café to its offerings. Even the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources is pitching in to sustain life in the Mountain State with its Hunters for the Hungry program, supplying deer meat to food assistance agencies around the state. “We’re doing this authentically, and not self-consciously, which is what makes it particularly compelling,” Wilson says. “I don’t think West Virginians fully embrace the fact that they have interesting ways of provisioning food.”

Reimagining West Virginia’s Food Economy

Models like the Alderson Green Grocer and the Heart and Hand House Community Garden Market may very well be the future of food in the state, bridging the gaps between charity, community, and capitalism. “The idea of social enterprise, of meeting basic needs in rural West Virginia, is very possible,” Kevin Johnson says. “People care. People want to shop at a place that fits with their sense of selves and community.”

In places like Whitesville and Weston, where the buildings that formerly housed large supermarket chains continue to sit vacant, it’s unlikely another corporate chain will come in. Whitesville community leaders have reached out to multiple chains from Piggly Wiggly to Dollar General. “They’re looking in more populated areas,” Hollie Smarr says. She and fellow community organizer Adam Pauley, both leaders with the Turn This Town Around program in Whitesville, go back and forth with regional corporations for weeks, and just as it seems they might be getting somewhere, discussions dissolve. “When they really take a look at the population, it’s out of their distribution area and there just aren’t enough people,” Smarr says. “I think right now a co-op or a community-owned grocery store is probably our best chance. It’s going to take a lot of support from the community, but I think it absolutely can be done.”

West Virginia’s communities working together—it’s not a new concept. Survival has been the name of the game since homesteaders first populated the mountains, since miners’ wives started vast gardens to battle the coal company store, since that first group of families pitched in to buy a cow and have it slaughtered. These are food desert strategies that aren’t discussed enough, Wilson says. “Yes, it’s all about community, but it’s also about survival. We always had to have some strategies in mind about how families would have access to good food, and that becomes part of the culture.”

He recalls a favorite childhood book, Blueberries for Sal, written in 1948 by Robert McCloskey. It’s the story of a little girl named Sal, her mother, and their trip into the country to pick blueberries for winter. Caplink, caplank, caplunk, sound blueberries dropped into an empty bucket. As soon as one falls, Sal scoops it up to eat, and her mother chastises her for eating the berries they need to can for the winter. “Why are there so many gardens in West Virginia? Well, Grandma always had a garden. Why did Grandma always have a garden? Because she had to make up the difference between what her family earned and what her family needed to put good food on the table,” Wilson says. “That’s a mentality that’s persisted in West Virginia—working to make up the difference. You have to put in a lot of extra work that is unpaid, that is unaccounted for, that is about building community and about love for people and all those other kinds of things that make people go above and beyond. We need to tap into that part of the story of West Virginia to rebuild a food economy.”

Written and Photographed by Katie Griffith

Leave a Reply