Master fiddler and Clay Countian John Morris is honored as a 2020 National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellow.

This is a story I should have shared long ago. But sometimes it seems that the most important stories often are overlooked because they are right in front of our noses. One of the driving forces behind the creation of this magazine stems from my deep-seated desire to positively reflect and capture our wonderful West Virginia heritage. But I’m not the only one in my family to be driven by this mission. My Uncle John Morris, a talented musician and songwriter from Clay County, began tirelessly championing the preservation of our mountain culture and music before I was even born. And this year, he received the nation’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts when he was chosen as one of the 2020 National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellows—the first West Virginian in 20 years.

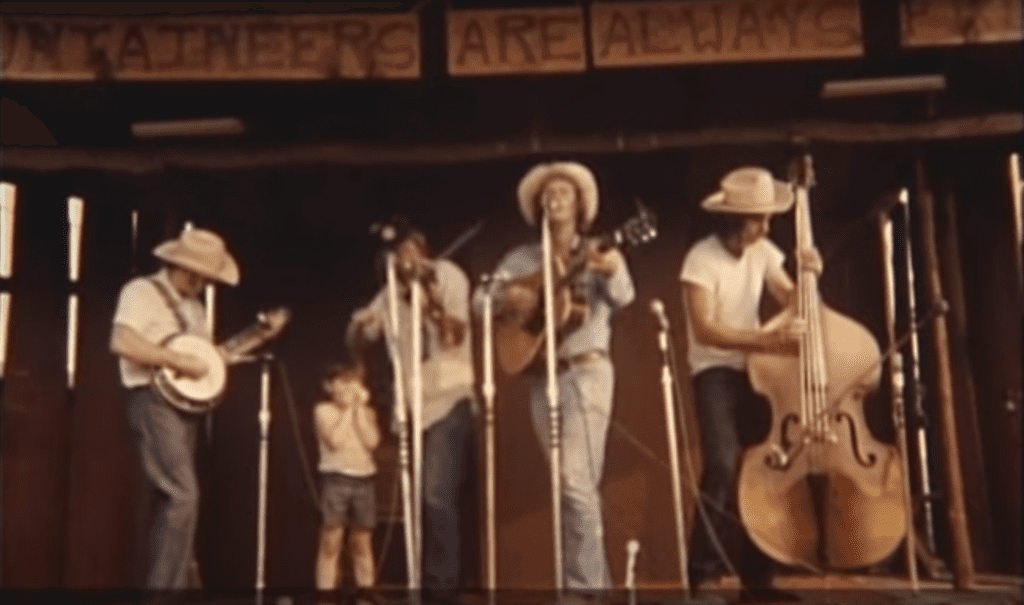

If you are a fan of old-time Appalachian music, you know the region owes much to him and his brother David—together they were known as the internationally acclaimed Morris Brothers. They helped preserve folk music, bringing it to the forefront in the 1960s and ’70s.

I recently sat down with Uncle John to talk about his life. I couldn’t help but be thankful for having grown up in an area surrounded by people who were not only proud of their heritage, but who stridently worked to protect it.

WV Living: Uncle John, my mission has always been to change perceptions of West Virginia, and not just how people from the outside look at us, but how we look at ourselves, and I’m ashamed to admit that I never thought about the similarity of our missions. All those years ago—before I was even born—you were preserving our cultural heritage and convincing people that it was worthy of saving.

John Morris: People have been fed the Hollywood image that goes back to the 1880s when the Hatfield–McCoy feud started, and the New York newspapers sent reporters to cover the feud. And that became the public image of mountain culture for many, many decades. And then we just started internalizing the outsider’s view of our own culture. And in a lot of ways, people tried to live up to that outside perception.

Then we have these television shows come in and they focus on moonshiners and rowdiness, fighting over ginseng holes and such, and that is hard to overcome. Once it is labeled, it’s hard to overcome that. We’ve internalized the idea that we are an inferior culture and that we need to be changed.

A lot of this business came about with the War on Poverty. People came in here and looked at us and found that we were poor and struggling—that we weren’t mainstream people because of the way we looked, acted, or talked. But the poverty here isn’t at the bottom—it comes from the top. And that never got addressed. It still hasn’t been. If you find somebody living in poverty and he can’t work and his family is down and out and his health is shot, ask, Why is his health shot? Find out what company he worked for. Then you get to see where the roots of poverty are. It isn’t in the behavior of the people. The plight of the people very often is not active, it’s reactive.

The goal of the War on Poverty was to turn our people into mainstream people, and the first thing they had to do was change the culture, which meant wipe out what was left of the old culture and replace it with something that was foreign to them.

WVL: You’ve spent your life trying to preserve our culture. Where did you get this passion for collecting, learning, and sharing old Appalachian tunes?

JM: We grew up surrounded by music, and we grew up with respect for old people. Our mother went to Glenville College, and she taught me how to play the guitar. At Glenville, she had written an English essay that said something should be done to preserve the old ways—that people who do all the old stuff would be passing on soon. Her professor was Dr. Gainer, and her paper sparked his interest. The two of them collaborated on the first West Virginia State Folk Festival at Glenville. My mother was always singing songs. My grandmother was always singing songs and hymns. I remember her singing songs like “Orphan Girl.” (John starts singing the lyrics.) My grandmother had a record player and we listened to Bill Monroe and Doc Watson. I’d play “What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul” over and over. (John sings the chorus as if it was emblazoned on his brain.)

WVL: Why is it so important to keep this musical heritage alive?

JM: Well, music is as much a part of history as the written word. And most music until recently was not written down. I just wanted to learn all that I could from the old folks. The music held on for so long here in Clay. This county was thickly populated with fiddle players. The fiddle is rather difficult to learn. There were a lot of people here who played it very well. For the most part, they are very charismatic people, welcoming people. And if someone showed some interest in their music, they’d take you right in. So I spent a lot of time with Clay County fiddlers Wilson Douglas, Ira Mullins, Lee Triplett, and Doc White. There’s an important story behind every tune.

WVL: After you graduated college, you wanted to be a teacher, right?

JM: I was a substitute teacher for half a year, and then I applied for a full-time job, but I was refused employment by the Clay County Board of Education. They said, “We talked it over and we are afraid that you will try to bring that music into the schools.” That music being old-time music. And that’s a direct quote. They were afraid that their children would be exposed to their own culture. I’ve never gotten over that.

WVL: You and David started your band—the Morris Brothers—in 1965.

JM: David was a great singer. He sang and I played. I could play straight music. I just picked it up real quick. I could hear a tune and then play it back. I tried to teach myself to read music, but it never worked out. To this day I can’t read music. You’d think that it would be easy—it’s just a bunch of symbols. You learn the alphabet alright, so it looks like you could learn 11 or 12 more things, but it didn’t work for me.

WVL: Tell me about the Morris Family Old-Time Music Festival.

JM: There weren’t any other festivals around. We was it. So we held the Morris Family Old-Time Music Festival to bring folks together focusing on the old traditional stuff. I think the first one was around 1968. It got really big. People came from all over the country. When you are doing it, you are just trying to get through the weekend. We never imagined it would grow like it did. And then after a handful of years the Vandalia people called us, and we helped them get the Vandalia Gathering started. We didn’t have anymore festivals here.

WVL: In 1975 you even had a television show—The Morris Brothers’ Old Time Music Show.

JM: We recorded about 15 shows for WOAY. It was bare-bones. They wanted us to work with one microphone and one camera. I think there were five of us in the band at that time, and we were used to having a guitar mic, banjo mic, and voice mics above them—a real sound system. We made the owner pay us per show. We didn’t play no place for free. We figured we were about as popular a bunch of people as there was around, and they was getting a good crowd. We got 100 letters the first show we done. We were paid $300 a show. That was good money then.

WVL: How did you get involved in the labor movement?

JM: David and I volunteered to be musicians for Joe Yablonski’s campaign for president of the United Mine Workers of America. At that time there were around 20,000 mine workers in the state who were under the thumb of the union with no real say. The union was operated from the top down, but Yablonski wanted to change that to a more democratic structure. We thought there was a chance for people to get a hold of their own lives and that would be a good thing for the whole state. If they could do that in the workplace, maybe they could understand how democracy is supposed to work in the political system and get more involved. So, we’d play our music and get people all fired up. It was a tense time. And then Yablonski, his wife, and daughter were murdered.

WVL: Because of your labor activism, your music became part of the soundtrack for the Oscar-winning documentary Harlan County, USA.

JM: We started getting some publicity and made it in the paper a time or two. I think old-time music is empowering. It’s stories about families and struggles. Music pulls people together. It rallies them. Back then, it helped stir people up.

WVL: You were always just my uncle. I didn’t really realize what a big deal the Morris Brothers were.

JM: Well, we got some press and got to travel to some places. We’d just meet people here and there. Some kid from Brown University came to our festival, and then he went back to school and said they needed to bring us to perform. So, then we went to Brown University and got paid $500. That was a lot of money then. We played in Chicago at The University of Chicago Folk Festival—that was a pretty prestigious one. We traveled to California and sang in Los Angeles and other places. I also sung in feed stores.

WVL: There was an article that appeared in the Los Angeles Free Press that said, “Both [John and David] are committed to preserving the cultural heritage of the southern Appalachian region and to helping the people of the mountains rediscover their roots and their unique identity. Both are also working to organize the mountain people to overcome the oppression and poverty which they face.” Do you think you’ve met your mission? What’s been your greatest accomplishment?

JM: I don’t know how to answer that. I guess just working with young people down through the years. I spent a lifetime learning from old people. I liked to pass on stuff. I just liked to play and entertain people with our version of old-time music.

WVL: Look at what you’ve done. You’ve been an educator your entire life. You’ve taught at the Augusta Heritage Center, Jackson’s Mill’s 4-H Mountain Heritage Weekends, at Pipestem, and a slew of other places. You’ve been inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame and served as a master artist in the West Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Program with Jen Iskow.

JM: Well, that’s just it. I’ve taught at camps all over. I have a student now I’m mentoring from Clay named Grant. He is as sharp as anyone I’ve ever seen. He is only 16 years old. He doesn’t miss a trick.

Everyone I’ve talked to has found value in what I do and who I am, except for the people I live in the middle of. They’ve scorned me. Stay away from the children, they said. We don’t want the children to know who they are, where they came from, what their past is. What do the children see on television? What is thrown at them in popular culture that is better than old-time music?

Old-time music says this: The tune is much better than the player. The tunes like Soldier’s Joy have lasted, some of them, 400 years. Look around—what modern popular songs last 400 or even 100 years? They last because they are good. Name a pop song that will last that long. There’s no star quality to the people playing old-time music. It isn’t about the person, it’s about the music.

WVL: Being named a NEA National Heritage Fellow is a big deal—only four West Virginians have ever been given this honor. You’ve got to be so proud.

JM: Well, the state folklorist Emily Hilliard nominated me. I told her the other day, if she could pull this off, she could pull off anything. So, I’d give her $200 if she’d get me a Nobel prize. This is a great honor. There’ve been a lot of outstanding people that have won it. I got to thinking: in 1970 I was on a two-week tour through the mountains of North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee. One night we were in North Carolina performing with Doc Watson, Hazel Dickens, Ralph Stanley—the four of us together on a show—and all four of us has won this prize now. Well, not being allowed to teach has always had a black place in my life. I endured a lot of ridicule over that, and bad jokes, and had to learn to walk on, but this award publicly says that this music has value. It says more about the music than it does about me. It means that maybe what I studied and what I’ve held near and dear has been worth it. It isn’t something that I just value, it’s something everyone should value. Now people have been calling from all over and interviewing me, and it’s like I’m an overnight success. But I’ve only been doing it for 60 years.

Leave a Reply