*If you’re a woman

A 10-step guide to busting up the old boys’ club.

When Agnes Queen was 32, she decided to run for county commission in Lewis County. She didn’t think she’d win, but she’d always been involved in the community and friends and neighbors were pestering her to put her name on the ballot. “The day of the election, before we left the house, my husband and I talked about it and said, ‘Well, we got your name out there. After this we’ll put your signs up and try again,’” Queen says. To her surprise, she won by more than 1,000 votes, beating an incumbent who’d been involved in politics for years. She was the first woman ever elected to the Lewis County Commission. “I was just so excited,” she says.

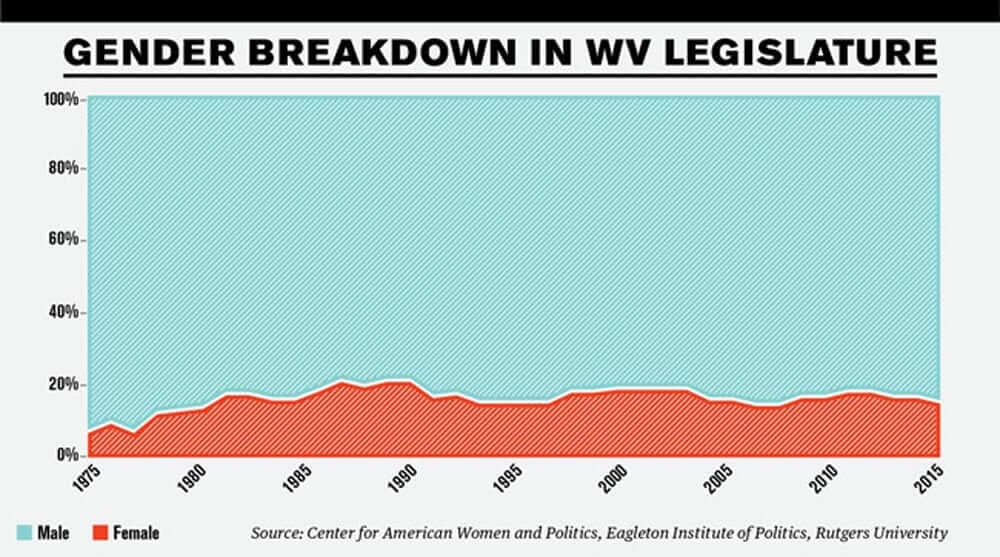

We might forgive those men because, frankly, the odds were against Queen. There were very few female county commissioners in 2007 and there are very few now. The same is true for just about every elected office in this state and nationwide. Women hold less than a quarter of the seats in state legislatures, and less than 20 percent of seats in Congress. It’s especially bad in West Virginia— there are currently only 20 women in the state Legislature out of 134 seats, and we’ve never had a female governor. Numbers on local offices are harder to come by, but most research indicates women are just as underrepresented in local and county elections.

The problem doesn’t boil down to sexist voters who won’t consider voting for a woman. Research repeatedly shows female candidates fare just as well as men at the ballot box, winning at roughly equivalent rates. The problem is, not enough women offer themselves up for consideration. Women simply don’t run for office.

And it might be getting worse. The West Virginia Legislature was 17 percent female in 1985. Now, 30 years later, it’s 15 percent female. And a 2013 study from the Women & Politics Institute—charmingly titled “Girls Just Want to Not Run”—found that, despite strides toward gender equality in recent years, young women today aren’t more apt to run for office than their mothers and grandmothers were. The authors surveyed 2,100 college students between the ages of 18 and 25 to assess political ambition early in life. “And our results are troubling,” they wrote. “Young women are less likely than young men ever to have considered running for office, to express interest in a candidacy at some point in the future, or to consider elected office a desirable position.” The authors proposed a number of factors that might hinder women’s political ambitions, most of which are troubling precisely because they don’t involve blatant sexism. This brand of gender inequality is sneakier, more deeply embedded. And harder to remedy. Young women, for example, tend to be exposed to less political information and discussion than men. Young men are more likely to have played organized sports and care about winning. Young men are more likely to have been socialized by their parents to consider careers in politics.

So, why should we care? Research shows that more women in elected office means a more transparent, inclusive, and accessible government. “They have perspectives that are a lot of times left out of male-dominated policymaking,” says Tara Martinez, executive director of the West Virginia Women’s Commission. And even though women care about all kinds of issues, research shows they champion issues related to women and families more often than men do. If we want to make significant progress on pressing social issues, we want more women in office.

In case you can’t make it to that workshop, we’ve put together a handy guide.

Step 1: Decide to run.

O.K., so, you’re ready to run for office! Let’s get started. What’s that, you’re not quite ready? You’re worried a campaign would be hard on your family, or take up too much of your time, or interfere with your career ambitions? Or you don’t think you’re smart enough, or have enough charisma or education? You’re concerned you’ll have to deal with grouchy old men who won’t take you seriously, constituents who have never cast a vote for a woman, or endless questions about your hair, your children, or your pantsuit? Or maybe the thought just never occurred to you?

Fair enough. Let’s go back a little.

Step 1, take 2: Care about an issue.

Usually, what this means is, “Get ticked off about something.” That’s true for all candidates but especially for women—maybe because they’re less likely to naturally picture themselves in office without that added drive. “With women, they often need some catalyst to get them involved,” Sinzdak says.

Take Nancy Cartmill from Barboursville. She spent time as a lobbyist on Capitol Hill and then in Charleston, but somehow didn’t make the mental leap to consider running for office herself. “It just never crossed my mind,” she says. “I just never thought about being a politician.” Then around 1993 she was appointed to the planning commission in Barboursville, where she lived. And did that little taste of power inspire her to run for office?

No, actually. Not at all. But here’s what did: “One day I was coming into town because I had a planning commission meeting. And I came to this traffic light where you have to wait and wait to make a left-hand turn. And I waited and waited and waited there while I was trying to get to my meeting and I just got so frustrated. I sat through that light three times.” When she finally made it to her meeting she walked up to the mayor— a man who had held the office for years—to talk with him about it. She wanted to know if there was room for a turning lane. “And he goes, ‘That’s ridiculous. You’re just a typical woman. You exaggerate everything. I don’t believe anybody has ever sat through three lights before they could make a turn.’”

Cartmill was shocked. And furious. “After the meeting a couple people came over to me and they said, ‘You should run against him,’” she says. “The next thing I know I’m at city hall picking up the paperwork.” She won that election, becoming the first female mayor of Barboursville, and when she decided to run again two years later she won that election, too. She won again and again until 2001, when she ran into a term limit and couldn’t stay in the mayor’s office anymore—so she got herself elected to the county commission. That’s a hugely successful political career spanning more than two decades—all because of a traffic light. “The funny thing is that nothing has been done with that light,” Cartmill says. “We really don’t have the room to make a left-hand lane there, so there’s nothing I could do.”

Step 2: Convince yourself you deserve the job

Step 2: Convince yourself you deserve the job

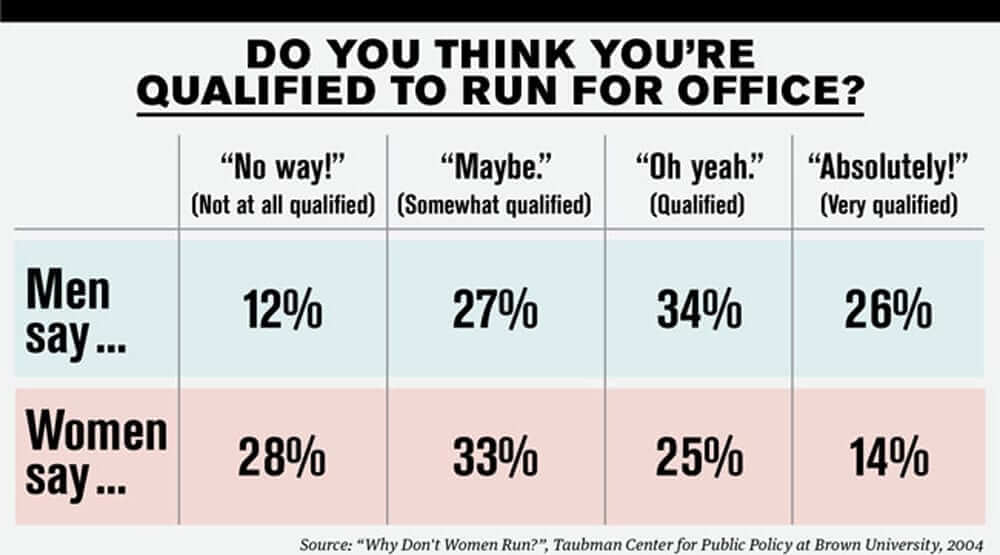

Most men think they’re qualified to hold an elected office. It sounds like a joke women would make to one another at a backyard barbecue while their husbands fuss over the grill, but it’s backed up by study after study. Most men really do think they’re qualified to campaign for office. And most women lack that self-assuredness.

When a 2004 survey asked men and women whether they were qualified to be a candidate, only 12 percent of men said they felt they weren’t at all qualified to run. More than a quarter of men, 26 percent, felt they were “very qualified.” For women, the results were pretty much the opposite. Only 14 percent of women thought they were very qualified to run, and 28 percent said they weren’t qualified at all. That means men are 60 percent more likely than women to think they’re very qualified for careers in politics. And that’s true even when the men and women have comparable educations and levels of success in their careers.

“It doesn’t make sense,” says Meshea Poore, who was in the West Virginia House of Delegates from 2009 to 2014. “You don’t have to be a lawyer to be a politician. You can have a GED and be just as qualified to do the things they do, because it’s not about the degree—it’s about communicating with the people well enough to convince them you can make a difference, and then following through with that when you get elected.”

Step 3: Get asked to run

Research has found that encouragement to run for office—by anyone from grandparents to the chair of a political party—has a huge effect on whether or not a person will eventually do it. And according to the “Girls Just Want To Not Run” study, men get told to run more often. Almost half of men say they’ve been encouraged to run by at least one person, but only 35 percent of women have. And this isn’t a problem that’s limited to powers within the political machine. Forty percent of men say their parents have encouraged them to run for office, but only 29 percent of women can say that. The men were also twice as likely to have had grandparents who encouraged them to get into politics. And that has a huge impact, because women are three times more likely to be interested in running for office if they have been encouraged to run.

So yes, getting asked to run is often a critical roadstop on the route from ordinary citizen to politician. But here’s the thing: It doesn’t have to be. If you’re a woman who’s considering running for office—or, heck, if you’re a woman who’s never considered it—here’s your encouragement. Clip this out and hang it on the refrigerator, or your bathroom mirror. Please, please run. We need more women like you to give it a shot.

Step 4: Decide to run.

Whew, we finally got there. O.K., let’s see what’s next.

Step 5: Plot.

Step 5: Plot.

If you don’t already know what office to run for, just pick one. If you don’t know who’s in that office now or what running against them might be like, find out. Bonus points if you’re going for an open seat—not that you can’t challenge an incumbent; it’s just harder that way.

Next, tell your friends and family you’re thinking about running. Tell leaders in your community and your political party. Talk about money with potential supporters. Figure out what you have to do to get your name on the ballot. And please, please, please follow through with all this stuff. Even among people who are interested in running for office, research says men take these preliminary steps toward becoming a candidate a lot more often.

Step 6: Get a thick skin.

When West Virginia Focus started calling around to female politicians for this story, we weren’t necessarily looking for women who had endured sexism in the political arena. But without even trying, we found them. Democrat or Republican, young or old, state or local election, almost without exception, every woman had some kind of story.

When Charlotte Lane got pregnant while running for the House of Delegates in the 1990s, she didn’t tell people until she absolutely had to—she didn’t want to have to deal with questions about how she’d balance her kid and her career. During Cartmill’s mayoral election she heard from a lot of people who said they were utterly confident she was qualified to do the job. But they still wouldn’t support her. “They’d say to me, ‘Nancy, I think you’d do a great job, but I can’t vote for a woman,’” she says. Barbara Fleischauer has been in the House of Delegates for 20 years now, but only recently got her first big committee appointment—she’s pretty sure being a woman has worked against her. “We’ve never had a woman Senate president, a woman speaker of the house, anything,” she says. “And we’ve had women serving for years—it’s not because the women were stupid.”

Betty Ireland, the first woman ever elected to the executive branch in West Virginia—and, consider this for a second, she was elected in 2005—is always very diplomatic about the whole sexismin-in-politics thing. But even she can’t help but relate a few funny anecdotes about her time in office and on the campaign trail. Like the time an older woman told her she wasn’t conservative enough because she hadn’t taken her husband’s last name. Or the guy who, during her 2011 gubernatorial campaign, took issue with her height. She’s nearly six feet tall. “He actually told me I was too tall to be governor,” she says. “But of course, this was coming from a very short man.”

Agnes Queen, that county commissioner who got mistaken for a secretary, says she had to work hard to convince people she’d be taken seriously if she was elected. “They’d say, ‘Those men are bigger than you—how will you make them listen to you?’” she says. “And I’d tell them I have ideas just like anybody else and I don’t have a problem voicing my concerns. Though they had a point—it is hard to get a man to listen to a woman.”

Step 7: Don’t let your skin get too thick.

Step 7: Don’t let your skin get too thick.

At the same time, every woman we talked with said the sexism isn’t that bad. Outside of a few rude comments and a missed opportunity here and there, they say their gender didn’t affect their campaigns or political careers. Some said, although they endured attacks based on their gender, if they’d been running as men they would have just endured different kinds of attacks. Many said they were motivated to work harder than their male competitors—and were grateful for that, because it translated into campaign success.

It bears repeating here: When women run for office, they win just as often as men do. There’s no reason to let gender stand between you and a career in politics.

Step 8: Get money.

“I think fundraising terrifies everybody,” Sinzdak says. Nobody is comfortable calling up friends, family, or acquaintances to ask for money. And women often feel at a disadvantage because their networks of acquaintances aren’t as vast as those of their male counterparts. While men are out hobnobbing after work, women are home tending to the stove or the house or the kids. “But at our sessions the trainers will say, ‘Let’s talk about the people you know,’” Sinzdak says. “And then they go through a list of people: You have other moms in the community, your friendship circles, your neighbors. Once they start making a list the lightbulbs go off over people’s heads and they realize they know a lot of people they can ask.”

Asking those people for money is probably never going to be fun, but here’s a helpful trick: “Reframe your thought process,” Sinzdak says. “A lot of people will ask for money for a cause they care about, but not for themselves. You have to think about it like you need this money to make your campaign successful—because once you’re elected you’re going to fight for those issues. You can’t think to yourself, ‘Oh, I need your money so I can print postcards for mailers.’ That’s not what it’s about.”

Research has repeatedly shown women and men are on equal footing when it comes to raising money, even when it comes to wooing early donors. So even though fundraising isn’t fun for anybody, at least it’s not more fun for men.

Step 9: Develop your message, build your team, talk to the public.

This part isn’t easy, but it’s a piece of cake compared with the epic battle you waged with yourself when you were debating whether or not to run. There are no hard and fast rules here, but we’ll leave you with some words of wisdom to get you through it:

“You better consider the passion before you run—you have to either have professional passion or political passion. And no matter how far up the ladder you go you have to love it, because politics now, more than ever, is bloodsport. You have to really have fire in your belly to run and withstand the scrutiny. That said, I think that women also need to realize they have the strength, they can run. If you have that passion it isn’t something you should have to second-guess yourself on.” Betty Ireland

“If someone has a desire to be in politics they certainly ought to pursue it. It might be hard at first but if you put together a good group of people and focus on yourself and what you can do you’ll be fine. When I got elected I thought I’d be a one-term mayor because I decided then and there I wanted to get things done that would make the city the best that I could make it, and I knew I wasn’t always going to do what had been done in the past and that I might not make people happy. But I found out just the opposite—people appreciated that I was there to get things done.” Nancy Cartmill

“As women, we have to make sure people know we’re confident, we’re qualified, we’re capable, we’re factdriven. They say we women are emotional, and we have to make sure when we’re taking on the opposition we are in a fact-driven mode to counter that. And yet, there’s nothing wrong with being emotional. That’s passion, and that’s good. I would be concerned about people who are not emotional when they see what is happening in our country today.” Meshea Poore

“I think it helps for women to stick together. We all have to keep trying.” Barbara Fleischauer

Step 10: Change the world.

Enough said. Run.

Written by Shay Maunz

Step 2: Convince yourself you deserve the job

Step 2: Convince yourself you deserve the job Step 5: Plot.

Step 5: Plot. Step 7: Don’t let your skin get too thick.

Step 7: Don’t let your skin get too thick.

Leave a Reply