Fifty-five years ago, Muhammad Ali became the heavyweight champion of the world for the first time.

Long before he stepped into the ring with Sonny Liston, Ali’s career was launched with help from the police chief of a small town in West Virginia.

In early October 1960, Associated Press teleprinters clattered to life in smoke-filled newsrooms across the United States. The harried editors assigned to monitor the machines couldn’t have known it at the time, but the rapid-fire hammers were pounding out words that would change the history of sports forever.

LOUISVILLE — Cassius Clay, the Olympic light-heavyweight champion, today signed for his first professional bout, a six-rounder against Tunney Hunsaker. Hunsaker, 29-year-old police chief of Fayetteville, W.Va., has a 15–7 record.

Although only 18 years old, Clay was already a global celebrity—not only for his gold-winning performance at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome, but also for his outsized persona. After his medal ceremony, he treated members of the press to a celebratory poem that began, “To make America the greatest is my goal, so I beat the Russian and I beat the Pole and for the USA won the medal of gold.”

Now that he was turning pro, Clay agreed to be managed by a coterie of 11 businessmen from his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. Choosing the first professional opponent for their star required careful consideration. Naturally, they wanted someone their man could defeat. But the opponent also needed to provide enough competition to showcase Clay’s fistic talents.

Although Hunsaker’s name probably did not ring any bells with newspaper readers, he was exactly the kind of boxer Clay’s people were looking for.

This is the story of a tobacco farmer’s son, a lifelong public servant, and a middling boxer whose athletic career might have been forgotten if not for a chance meeting with a man who would become the most famous athlete of all time.

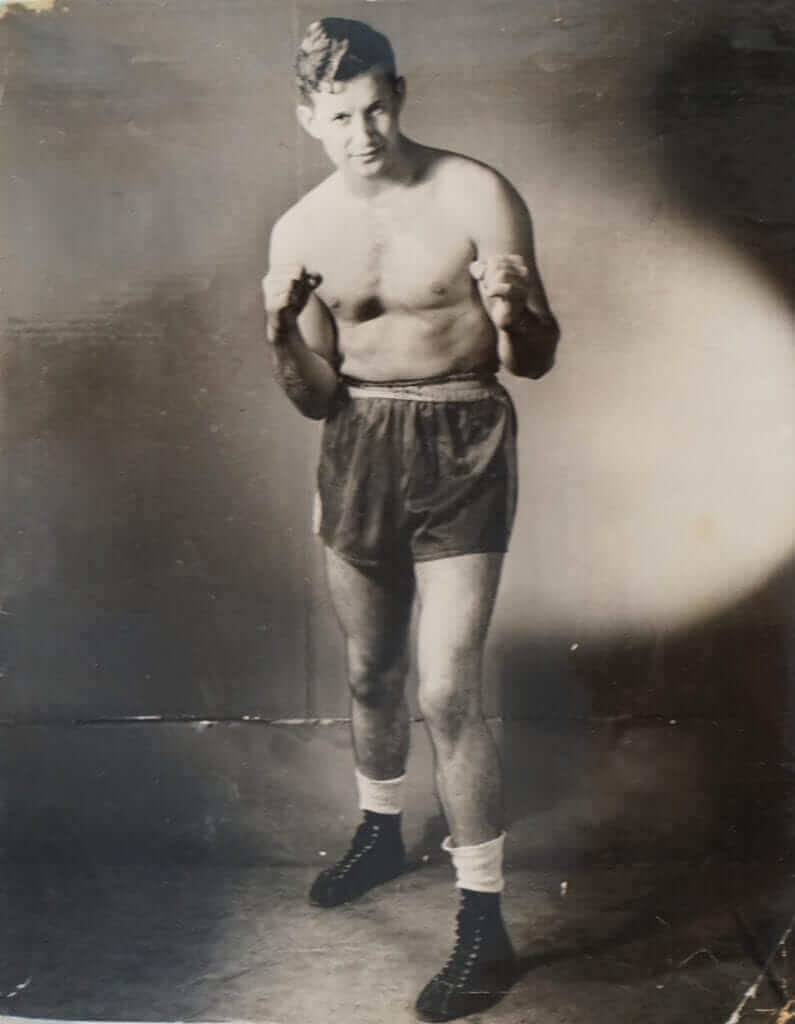

Born in 1930, Hunsaker grew up on a tobacco farm in Caldwell County, Kentucky, about 170 miles southwest of Clay’s native Louisville. His father was a fight fan, naming his son for the 1920s heavyweight champ Gene Tunney.

It must have come as no surprise, then, when Hunsaker fought his first bout at age 14 in a makeshift ring at his high school. He continued boxing after joining the U.S. Air Force and became base champion at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, a title he held from 1951 until he was honorably discharged two years later. Hunsaker was also the 1951 Golden Gloves champion in San Antonio, Texas. After going pro in 1952, he fought to a 12–2 record and was named “Prospect of the Month” in the June 1953 issue of Ring magazine.

But just as his career was gaining momentum, Hunsaker threw in the towel. His hitch with the Air Force was up and his mother-in-law—who lived in Oak Hill, West Virginia—informed him that nearby Fayetteville was looking for a police officer. Hunsaker got the job in late 1955, packed up his wife and young daughter, and headed for the hills.

There was little time now to think about boxing. Hunsaker became chief of the town’s two-man police force after less than a month on the job, and his days were filled with rounding up AWOL soldiers, breaking up fights at football games, and ticketing license-less drivers. He hunt-and-pecked his own reports on a manual typewriter and, because his office was not equipped with a telephone, answered calls in a phone box outside the Ben Franklin five and dime.

While working the beat, Hunsaker met Skippy Gray, the 16-year-old son of the local grocer. Gray was a scrappy kid, always getting in fights. Hunsaker offered to train him for the Golden Gloves and the two began working out in a makeshift gym in Oak Hill.

He found his way back into the ring in 1958, winning five of his first seven fights. In the year leading up to the Clay fight, though, Hunsaker’s hot streak had cooled. He lost each of six fights leading up to the bout. Yet he remained optimistic. Writing to a childhood friend, Hunsaker predicted he would knock out the loudmouthed young fighter in an early round. “I have fought men whose record proved that Cassius Clay shouldn’t even be in the same town as them.”

No one else was quite so confident in Hunsaker’s ability, but sportswriters admitted he would not be easy prey. “Hunsaker is no Sonny Liston, but Hunsaker’s no cream puff,” wrote the Louisville Courier-Journal, referencing the then-reigning heavyweight champion of the world. “He hasn’t been dug out of the graveyard at midnight either and propped up on a Halloween broom to furnish Clay a target to shoot at.”

Hunsaker drove to Louisville with his friend John Witt, who would later become Fayetteville’s mayor. The fight was to take place at Freedom Hall. Hunsaker had fought in the cavernous arena twice before, winning the first time but losing the second. They arrived to a less-than-packed house. The building could seat 20,000 but only 6,200 people showed up to see the fight.

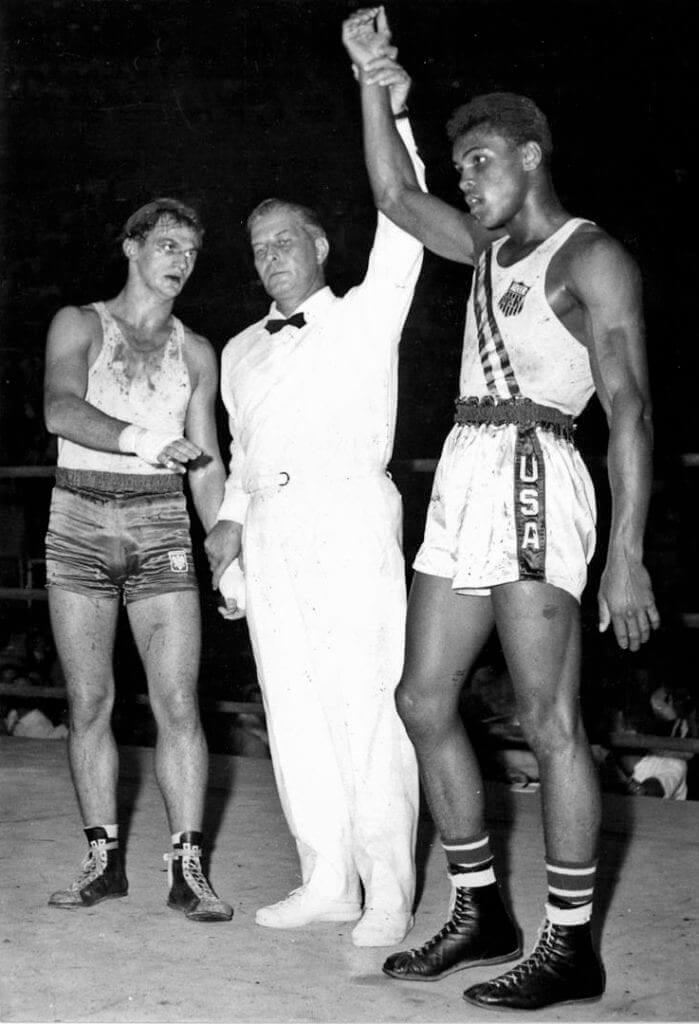

This didn’t seem to bother Clay, who acted as if the house was packed to the rafters. He arrived at the ring surrounded by a large entourage. Hunsaker, by contrast, was accompanied only by a few men working his corner. It did not matter, though. As the opening bell approached, everyone else slipped into the darkness of the arena. Only Clay, Hunsaker, and the white-shirted referee remained.

One wonders if Clay, looking at Hunsaker in the opposite corner, thought back to another boxing policeman—Joe Martin, the Louisville officer who taught him to box and changed the course of his life forever. There is no way to know. If Clay had any warm feelings toward his opponent, it is not evident in the newsreel footage that survives of the fight.

The jittering black-and-white film shows Clay’s impressive speed on full display. He deftly avoids Hunsaker’s blows, sometimes sending the older boxer stumbling when a punch fails to connect. He is also quick to invade Hunsaker’s space, delivering a jab and then getting out of the way in a blink. This was four years before the phrase “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” would forever establish itself in the national consciousness.

Clay concentrated his punches on Hunsaker’s face. His jabs busted the blood vessels in Hunsaker’s nose. By the end of the third round, it was bleeding freely. The bell clanged and the fighters returned to their corners for a short respite—too short for Hunsaker. In an instant they were back in the middle of the canvas to begin the fourth round. Clay continued his assault on Hunsaker’s face. By the end of this round, both of his eyes were nearly swollen shut.

Still, Hunsaker fought on. He continued absorbing Clay’s jabs throughout the next two rounds, taking a beating but mostly remaining on his feet. At the end of the sixth and final round, Clay’s pristine white trunks were stippled with blood. It was not his own.

The judges tallied their score sheets and the result was unanimous. The hometown hero had won every round. Clay’s professional record now stood at 1–0.

Although the fight would go down as an “L” on Hunsaker’s record, it did provide one point of pride. Of the 20 fighters Clay defeated on his way to the title, Hunsaker was one of only six who went the distance with the future champ.

Displaying his usual bluster, the “Louisville Lip” was a sore winner. “That Tunney Hunsaker I fought Saturday was too easy—I was fresher after the fight than I was before.”

Hunsaker, though, was generous with praise for his opponent. Although he said Clay, who turned up to the fight in a pink Cadillac, was too “spoiled” by his backers, Hunsaker told Charleston Daily Mail sports editor Dick Hudson the 18-year-old had real talent. “He’s very fast and can hit,” he said. “The kid can be the heavyweight champion of the world some day. He’s that good, if he settles down to hard work.”

This prediction came true, of course. On February 25, 1964, Clay defeated Liston by technical knockout to gain the world heavyweight title.

Then things began happening that no one could predict. Two days after the fight, Clay confirmed rumors that he was a member of the Nation of Islam. The following week, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad announced that Clay would now be called Muhammad Ali. Three years later, Ali was stripped of his heavyweight title—not because he lost a boxing match, but because he refused to be drafted into the U.S. military in protest of the Vietnam War.

For better or worse, Ali né Clay was more famous than ever. Hunsaker, meanwhile, had stepped away from the spotlight.

In February 1961, he left the Fayetteville police department to become an inspector with the state beer commission. He continued boxing but success eluded him, just as Ali had. He gained some national recognition in September 1961 when he traveled to the West Virginia State Penitentiary to fight inmate Thomas Dejarnette, the heavyweight champion of the prison. He lost by technical knockout in the eighth round.

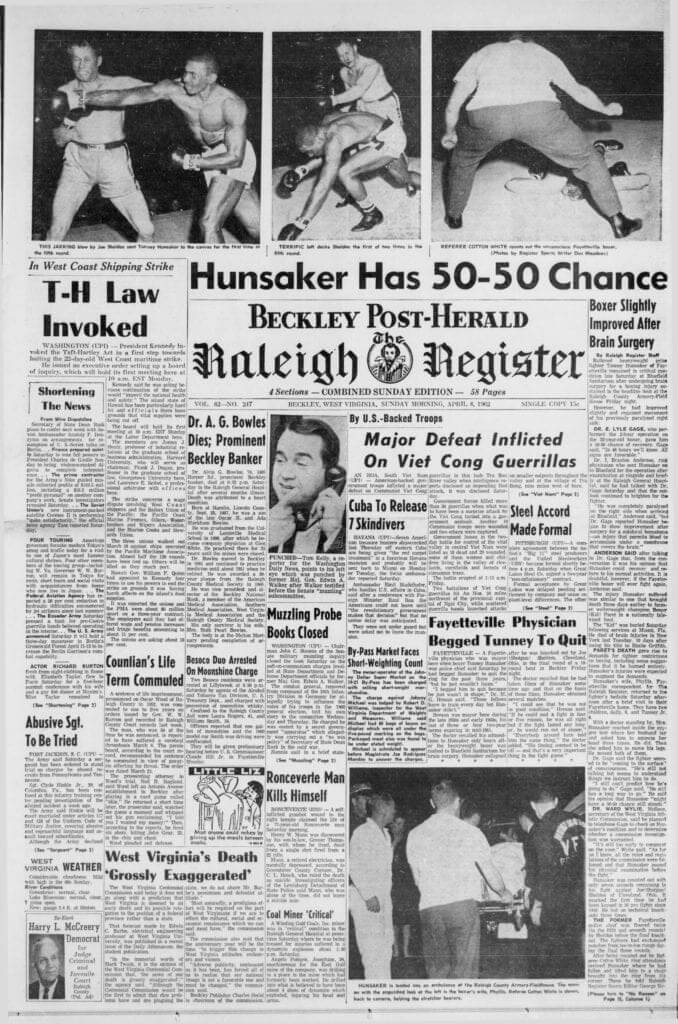

This was becoming standard for Hunsaker. He won only two of his next six fights, which is why some worried how he would fare during 10 rounds with Joe “Shotgun” Shelton, scheduled for April 6, 1962.

Shelton, who hailed from Cleveland, Ohio, weighed in at 192 pounds and stood six-feet- one-inch tall, with 17-inch biceps and a body that looked like it had been chiseled from marble. One reporter described his physique as “more like a bodybuilder than a boxer.” Hunsaker was two inches taller than Shelton, but his 32-year-old body now weighed about 200 pounds, nearly 20 pounds heavier than he had been against Ali. Although he was fit, his frame belonged to an earlier generation of pugilists.

Raleigh Register sports editor Greg McLaughlin, a friend of Hunsaker’s, told readers the fight would be difficult for the former police chief, although victory was not out of reach. “Just flip a coin,” he wrote. “It’s going to be that close.”

This prediction proved frighteningly accurate.

Three photos ran at the top of the front page of the April 8, 1962, edition of the Raleigh Register. In the first, the camera captures the aftermath of a rushing right-hand blow by Shelton. Hunsaker’s face is contorted from impact. In the second, Shelton stumbles from the force of a left from Hunsaker. In the third photo, we see the large posterior of referee Cotton White. He is counting out Hunsaker, who lies face-down in the ring, his legs splayed unnaturally.

The headline: “HUNSAKER HAS A 50–50 CHANCE.”

The fight had been a brutal one, with both men sustaining significant damage but staying upright. By the beginning of the 10th and final round, it appeared the winner would be determined by judges’ decision. Then, with less than 30 seconds to go, Shelton caught Hunsaker with a hard left to the right temple. He collapsed onto the canvas.

When White reached the end of his 10 count, ring attendants lifted Hunsaker onto a stool where he regained enough consciousness to tell McLaughlin, “I want to fight him again. I’m OK.” But while being examined by fight doctor I. Braxton Anderson, he collapsed again.

By the time Hunsaker arrived at the Bluefield Sanitarium, still shirtless and wearing his trunks and boxing shoes, he sported a black eye and a bruise on the side of his head, and his right side was paralyzed.

Doctors discovered a bleed on the outside of his brain and rushed him into emergency surgery to relieve the pressure. After the two-hour procedure was complete, Dr. E. Lyle Gage told members of the media the outcome was uncertain. “In 48 hours, we’ll know,” he said.

Once again, Hunsaker made headlines. His fight with Shelton had occurred on the same day former welterweight champ Benny “Kid” Paret was laid to rest. Paret had died the previous Tuesday, 10 days after suffering a similar brain bleed in a nationally televised fight. The coincidence was too much for the public, and many called for boxing to be banned. This included Hunsaker’s wife, Phyllis. Speaking to reporters as she exited her husband’s hospital room, she said, “I hope they ban boxing, I’m against it all the way.”

Cards, prayer cloths, and flowers poured into Hunsaker’s room as newspapers worldwide followed his progress. He was finally released from the hospital after 17 days. Gage offered one piece of advice as he left: “Do not return to the ring.”

Later, in an interview with McLaughlin, Hunsaker conceded he would be “stupid” to return to the sport—although the money wouldn’t hurt, given the medical bills he had incurred.

Hunsaker had no memory of his fight with Shelton and asked his newspaperman friend how it had gone. McLaughlin told him the crowd had applauded after each round. “If that was going to be my last fight, I’m glad it was a good one,” he said. “I wanted to please the crowd.”

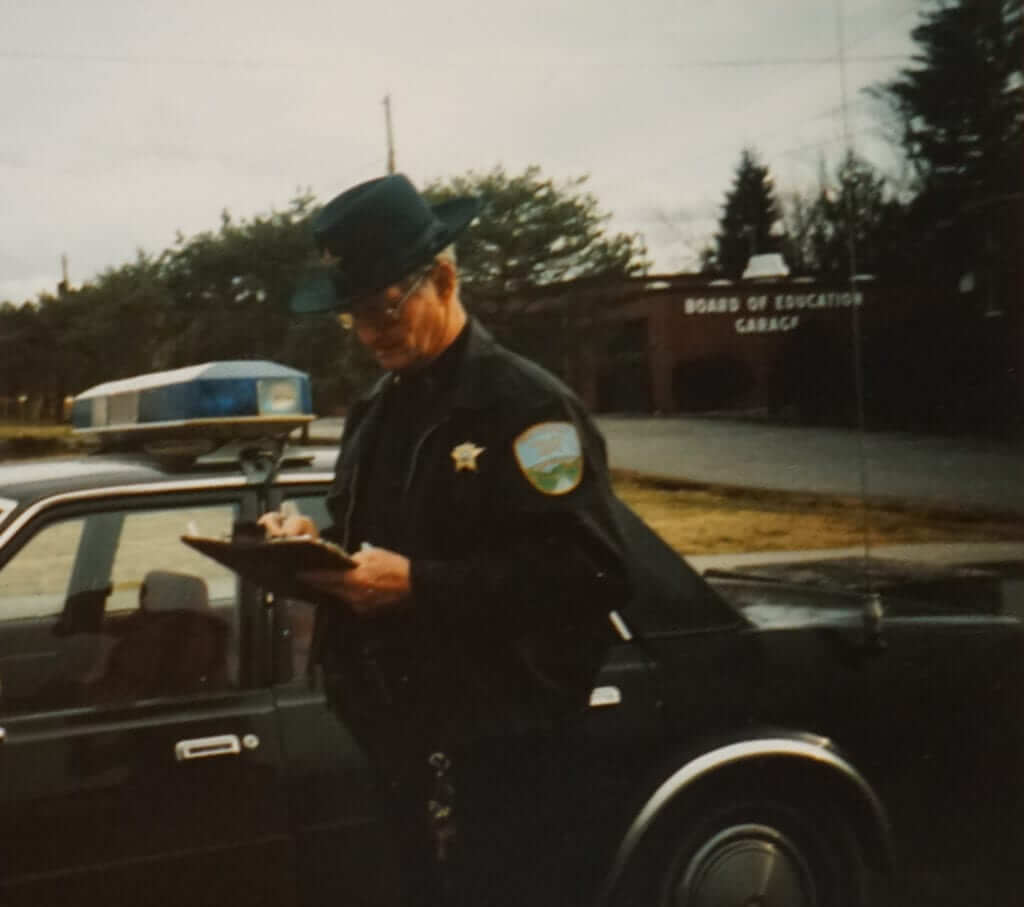

Hunsaker had no trouble building a life outside the boxing ring. He left the beer commission in 1967 to return as Fayetteville’s police chief—a job he would hold for the next 25 years.

Around that same time, he met a young woman named Patricia Halstead. He and Phyllis had divorced shortly after the Shelton fight and, though Halstead was 13 years his junior, the two became smitten with one another and eventually married.

While he had once been a brash young police officer, Hunsaker now became Fayetteville’s homegrown version of Andy Taylor, driving widows home from the grocery store, directing traffic for the local elementary school, and spending so much time walking the beat that his wife was continually buying him new shoes. The children of Fayetteville, when asked what they wanted to be when they grew up, did not say “policeman.” They wanted to become “a Tunney.”

Hunsaker also became a Sunday School teacher at the Oak Hill Church of the Nazarene, taking over the junior boys’ class. “He wasn’t a scholar, but he got that Bible and he tried the best he could. He taught by example more than anything,” Pat Hunsaker remembers now.

He took his students on camping trips to Bluestone Lake, invited them to his big Victorian home on Fayette Avenue to bake cookies, and, when the boys kept up good attendance or invited friends to church, gave them cheap watches he bought at the local auction house. “They would work for those watches,” Pat says. The church named Hunsaker “teacher of the year” for the 1983-84 and 1984-85 school years and, in 1987, he was named “teacher of the year” by the Nazarene organization’s West Virginia South District.

Still, his six rounds with the fighter formerly known as Cassius Clay followed Hunsaker like a shadow. It became local lore, the kind of story fathers would tell sons when they passed Hunsaker on the street. It was international lore, too. Decades after the fight, Hunsaker still received fan mail from all over the world. He was featured on the game show To Tell the Truth, where Soupy Sales correctly identified him as Ali’s first opponent. Then, in the 1980s, he and Pat drove to Ottawa, Canada, for Hunsaker to appear on a similar show called Claim to Fame. This time he stumped the panel, winning $500—more than he’d made for the Ali fight itself. He used the money to take his wife out to dinner at one of those French restaurants where the waiters wear white towels across their forearms.

It was 20 years after their original meeting that Hunsaker again crossed paths with the man who made him famous.

Ali retired from boxing in 1981 following a disastrous showing against Trevor Berbick in the Bahamas. But, like Hunsaker, he had little difficulty transitioning into life outside the ring once his fighting days were finally over. Time had tempered his once-radical views on race, religion, and politics. He now traveled the world promoting peace, even as Parkinson’s Disease slowed his movements and snatched away his smooth speech. “I’ve always wanted to be more than just a boxer,” Ali once told an interviewer. “I wanted to use my fame, and this face that everyone knows so well, to help uplift and inspire people around the world.”

In 1987, Ali used his face and fame to help out some boxing boosters in Charleston, West Virginia, who were trying to revive local interest in the Golden Gloves. Event promoter Bill Picozzi booked Ali for an autograph signing at the Charleston Civic Center to raise awareness and money for the effort. Picozzi also invited Hunsaker to lend the event some historical gravitas.

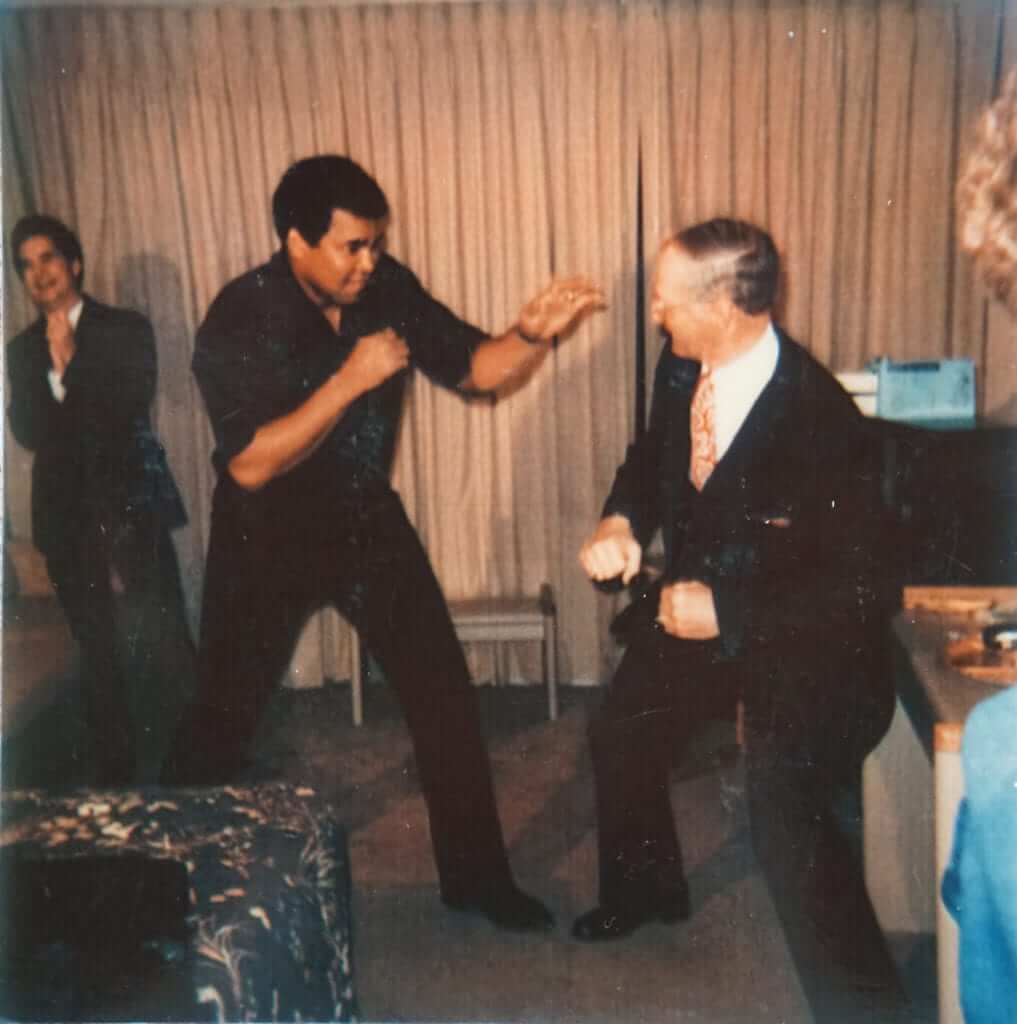

Although they had not seen one another for 27 years, the former opponents acted like old friends, joking and throwing fake jabs. The event went so well that the autograph signings became a regular occurrence.

During what would prove to be the final one, in February 1992, Ali learned that Hunsaker was retiring from his position as police chief, and he wanted to do something special for his foe-turned-friend. “Ali said, ‘I want to come to your hometown.’ Well, we had nothing prepared,” Pat says. The Hunsakers rushed home that afternoon, booked a conference room at the local Comfort Inn for the next day, and called everyone they knew to invite them to the impromptu retirement party.

After the party, the outgoing police chief treated him to a grand tour, even stopping traffic on the New River Gorge Bridge so Ali could walk out to the middle. They visited a local flower shop, where the proprietress pinned a bud to Ali’s jacket. When the champion noticed a school bus of special needs children passing by, Hunsaker flagged it down so Ali could climb aboard and interact with the students.

As they ended their day together, Ali remarked that he would like to come back to Fayetteville for something less public, like dinner at the Hunsakers’ home. Pat told him he was always welcome, but the meeting never came to pass.

Like Ali, Hunsaker was beginning to see the after-effects of so many punches to the head. He would get lost while driving on his own. Later, when Pat took his keys away, he’d wander out of the house and walk through town. She would follow him, walking for miles until he collapsed from exhaustion. Then she would get someone to drive them home. People were always happy to help, she says. Hunsaker had spent so many years watching over the town, now it was time for the town to repay the favor.

Doctors at West Virginia University in Morgantown eventually diagnosed him with dementia. Still, he told Pat he did not regret his time as a boxer. “I regretted it for him,” she says.

When Hunsaker died in April 2005, his name appeared on the Associated Press newswire for one final time—although the clattering teleprinters had now been replaced by websites and emails. At the wake, Pat listened for hours as mourners shared memories of her late husband. “Anyone who ever met him, even briefly, had a story,” she says.

Hunsaker was laid to rest at Fayetteville’s Huse Memorial Park. He is buried in the veterans’ section of the cemetery beneath a tombstone carved from highly polished black granite, not unlike the material that was eventually used for Ali’s own grave marker when he passed in 2016.

On the left side of the gravestone, Pat had two engravings made. On top is a portrait of Hunsaker in his police uniform. Below that is a drawing of a much younger man ducking a punch from Cassius Clay.

At the bottom of the marker, there is a scripture from the New Testament.

“I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith.”

Leave a Reply