Whether you’re a home chef or an avid hunter, having a proper knife is essential. This everyday tool seems simple, but crafting one whose form is as sharp as its function takes a true master. Meet the West Virginians who are forging ahead in the ancient art of bladesmithing.

WRITTEN BY JESS WALKER, PHOTOGRAPHED BY CARLA WITT FORD

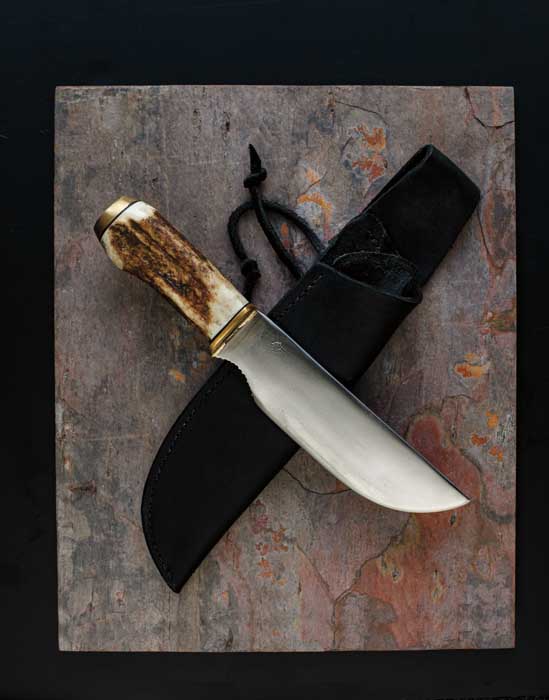

DERR KNIVES

In the early ’90s, Herb Derr took a class on making damascus knives. Within a year, he sold his previous business and committed to forging. “Being an artist, you’re always looking for that one thing where you can make a living and not get burnt out,” he says. Nearly three decades later, Derr’s passion for damascus is still burning strong. The metals for damascus steel are repeatedly layered and fused to give the blade an appearance of rippling water. Derr adds nickel for a bright sheen and twists the metal or drills holes to create a bird’s-eye pattern. His blades are sole authorship from point to handle, and he inlays the sheaths with exotic leather—the pictured one features cane toad. Derr travels to three knife shows annually and sells through a handful of dealers. He doesn’t have a website himself, so how does a knife enthusiast find out more? “Google Herb Derr.”

LIFE’S FORGE

Books plunged Bennett Life into the worlds of blade and blacksmithing. Inspired by the Foxfire series—a collection of stories about Appalachian culture—the then-14 year old built a forge and kept his nose to the grindstone. “I wanted to be able to handle every area of bladesmithing and blacksmithing that I could,” Life says. What started as a self-taught hobby turned into a full-blown business called Life’s Forge. Life spends eight hours a day crafting anything from fireplace pokers to medieval daggers to table legs. For the knife he sent WV Living, he welded together ball bearings and two other kinds of steel in a can to create the metal. Most of his knives demand 10 to 20 hours of labor, but Life once spent 100 hours on a 3-foot-tall tree statue complete with dangling leaves and snaking roots. He sells his masterpieces and provides coal forge demonstrations at local art shows. lifesforgewv.com, @lifesforge on Facebook

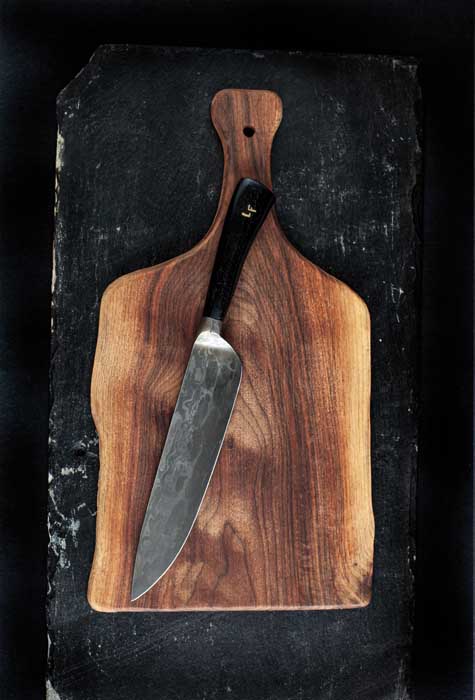

CROOKED RIVER FORGE

When Tommy Matthews’ sales job in the steel industry quenched out, he sharpened up his bladesmithing skills. Chef ’s, hunting, and everyday carry knives from Crooked River Forge are made with steels Matthews knows well, such as 1095 high carbon steel, to ensure dependability during heat treating. He leaves hammering dimples visible both for aesthetics and to prevent food from sticking— an important factor since chefs country-wide wield the blades. An avid outdoorsman, he says, “I wanted to make knives I could use, whether that’s from skinning a deer and processing it to cooking and eating it.” What thrust Crooked River Forge into the limelight was Matthews winning the “Steel Takedown Bow” episode from season 5 of the History channel’s competition series Forged in Fire. He’s since moved from Cleveland, Ohio to his hometown of Chester. “I don’t think a day goes by where people don’t stop in to catch up.” crookedriverforge.com, @crookedriverforge on Facebook

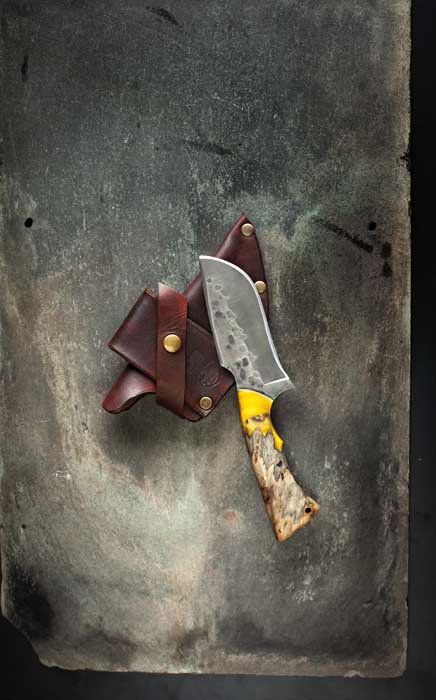

HOUSE OF STEEL: THE LEGACY OF LITTLE JOHN

The Big Bad Wolf demolished the three little pigs’ straw and stick houses. So Luci McDonald Vanilar told her late husband Little John McDonald to name their blacksmithing business House of Steel because “you can huff and puff, and you’ll never blow it down.” House of Steel’s artisans use a primitive coal forge and hand-hammer blades, rarely running machines beyond small power tools. All are trained blacksmiths: Jimi Miljko continues McDonald’s bladesmithing style, McDonald Vanilar crafts handles and sheaths, and her son and daughter-in-law etch glass and carve horns. House of Steel has traded blades for everything from antlers to sausages. And just how tough are they? When a Viking reenactor passed, his wife received permission for a traditional Viking cremation with his knife collection. House of Steel’s blade withstood the fire, and they repurposed it for her. The knives have a lifetime warranty but, McDonald Vanilar says, “We have what I jokingly call an afterlife warranty.” @houseofsteelblacksmiths on Facebook

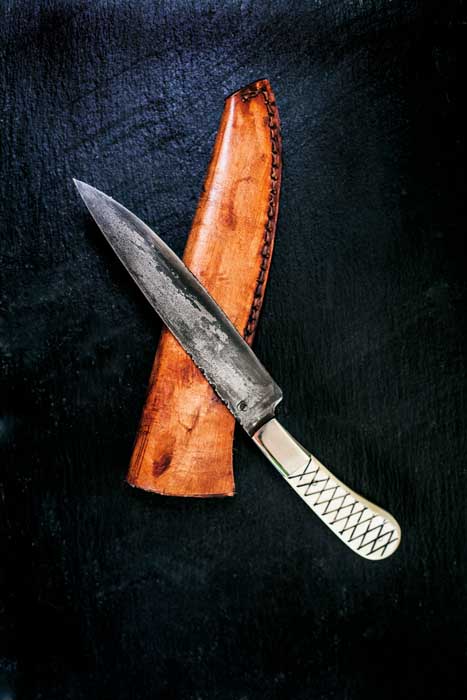

BRAY’S KNIFEWORKS

Greg Bray and his father were both knife collectors so, after Bray observed a local craftsman, he tested his own metal—er, mettle. The first knife he made in 1990 looked a tad crude, but he honed his talent throughout the years and ventured into blacksmithing. Bray currently works as executive director of Pricketts Fort Memorial Foundation, so much of what he crafts at his home forge on evenings and weekends are historical 18th or 19th-century designs of axes, knives, and tomahawks. “Even though they were simpler knives back then, there was still beauty in them,” he says. The one pictured is a 19th-century pistol grip made from files with a crosshatched bone handle. Bray used to travel to craft shows, and his knives have found homes throughout the United States and Europe. He sells through word of mouth now, but teaches a blacksmithing class at Prickett’s Fort State Park annually. 304.825.1288

Leave a Reply