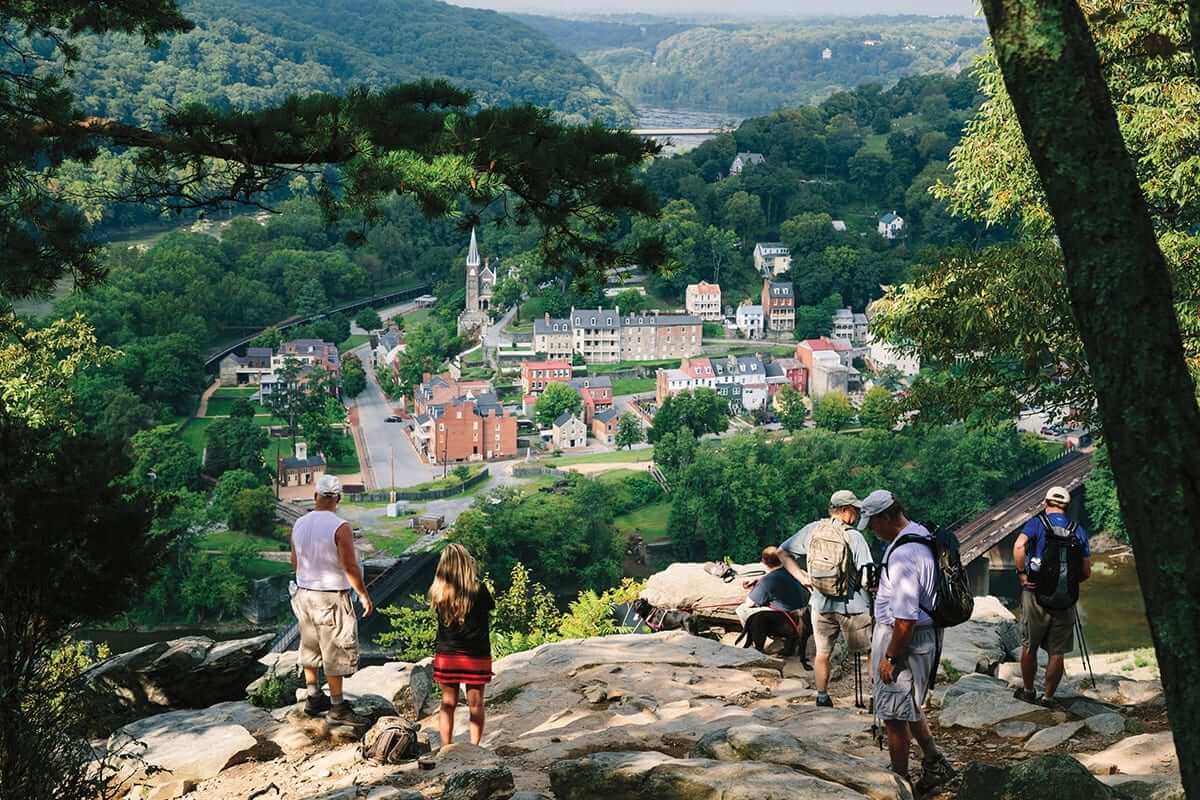

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

In 1761, the Virginia General Assembly approved Robert Harper’s request to run a ferry near the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. The legislature dubbed the town “Shenandoah Falls at Mr. Harper’s Ferry.” Two decades later, a young future president Thomas Jefferson passed through the area. After surveying the area from the site known today as Jefferson Rock, he wrote, “This scene is worth a voyage across the Atlantic.” In 1796, Harper’s heirs sold 125 acres of land to the U.S. government. The feds built an armory and arsenal on the site—a move that would etch the little town’s name into United States history forever.

In October 1859, radical abolitionist John Brown and his 21-member Provisional Army of the United States led a raid on the Harpers Ferry armory, intending to seize the 100,000 weapons held there before retreating into the Blue Ridge Mountains. Once there, they planned to engage in guerilla warfare to spark a slave uprising. Needless to say, it didn’t go as planned. Brown and his men quickly found themselves in a stand-off with troops from Maryland, Virginia, and The District of Columbia. The conflict lasted three days and was only brought to an end once U.S. Marines stormed the fire engine house where Brown was holed up. The structure is now known as “John Brown’s Fort.”

Although Brown’s revolution did not come to pass, the episode only deepened divisions in the country, helping to spark the American Civil War. Both North and South recognized Harpers Ferry’s strategic value—not only because of its proximity to major waterways, but also because it was located along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. As a result, the town changed hands between Union and Confederate forces eight times between 1861 and 1865. This would prove ruinous for Harpers Ferry. When Virginia voted to secede from the United States of America—putting the town in enemy territory—Union soldiers set fire to the armory as they retreated to keep the weapons it held out of Confederate hands. Southern troops were able to put out the flames and salvage some of the equipment but, when the Union later reclaimed the town, the Confederate Army burned most of factories and demolished a railroad bridge.

The years following the War Between the States brought more changes to Harpers Ferry. Decades of development destroyed much of what was left of its historic architecture. But local historians pushed to protect the town. West Virginia’s Congressman Jennings Randolph took up their cause and, after several failed attempts, convinced Congress in 1944 to designate Harpers Ferry as a National Monument. This brought nearly 4,000 acres into the National Park Service, which began returning the streets to the way they looked in John Brown’s day. It was 19 years later, in 1963, that Congress officially declared the area a National Historical Park. The park is now renowned for its walking trails and serves as the midpoint of the 2,178-mile-long Appalachian Trail. But more than that, it gives visitors an opportunity to catch a glimpse of one of the most tumultuous times in American history. nps.gov/hafe

Photos courtesy of Chris Weisler

Leave a Reply