Ditch your cell phone and ride your accommodations to your destination on the Durbin & Greenbrier Valley Railroad’s Castaway Caboose.

Back in the day, when freight trains had rear crews to manage their nether operations, the caboose was a place of exertion and sweat. Today, thanks to the Durbin & Greenbrier Valley Railroad, it’s a place of pure and private relaxation.

Here’s how John Smith describes the experience of his railroad’s two Castaway Cabooses. “You will be taken by train in your own railcar down into the wilderness and cast away—your caboose will be left on a siding by the tracks and there will be nobody within miles of you.” He’s not exaggerating. There aren’t many places in the eastern U.S. more remote than the heart of the Monongahela National Forest. The nearest town is many miles away from this siding by the Pocahontas County origins of the Greenbrier River. There’s no road around. And there’s absolutely no cell service: The cabooses are cast away in the National Radio Quiet Zone that enables the Green Bank National Radio Astronomy Observatory to function.

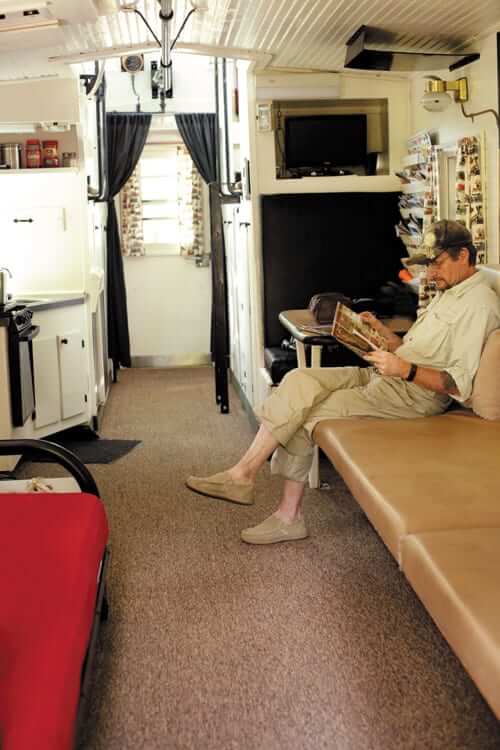

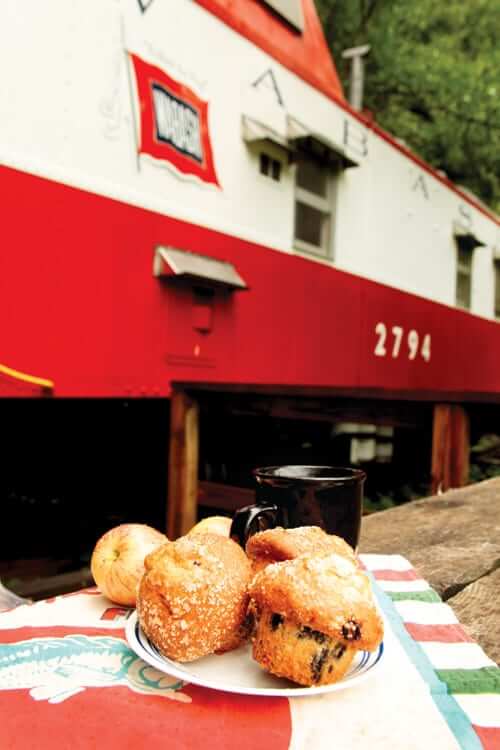

But no worries—guests have all the comforts in these two cottages delivered to the wilderness by rail. “We took the guts out of two Wabash Railroad cabooses and made them basically into RVs with refrigerators, sinks, stoves, and even ovens, and full-size showers and baths,” John says. “You also have grills on the back platforms.” Propane powers the stove and heats the shower, and solar panels charge 12-volt batteries that run lights and a water pump.

Alongside the modern comforts, guests enjoy all the charm of a caboose that dates to the 1950s and was originally designed to house railway employees. “You had a crew of two or three at the back end of the train,” John explains. “They could look ahead and see if there were any derailments or hobos or other obstructions. And when the train would stop to pick up other cars, they’d do that work from the caboose. They ate and slept back there—it’s kind of a romantic notion.” D&GVRR’s castaway cabooses retain the cupolas on top, where rear crews sat to monitor train and track. They have the original bunks, updated for comfort. “And we refurbished the windows but they’re the same exact windows, with the original screens,” John says. “It’s very, very cool.”

Both drop-off points have picnic tables at overlooks on the Greenbrier River. “We have these beautiful places on the Greenbrier River, in the middle of the national forest, that are just begging people to stay—you see bears and bald eagles all the time,” John says. “It’s just such a wildernessy, scenic spot.” The combination of the refurbished cabooses with the remote beauty is unique, in his mind. “Lots of people have turned cabooses into cabins. But I haven’t seen anyone who’s taken that to a really neat spot and dropped it off. This is about the coolest thing you’d ever want to do in the woods.” An important part of the experience, says this train buff, “is that you ride in your own accommodation, just like the guys who manned the cabooses did.”

The Castaway Caboose trip is a May through October add-on to the tourism railroad’s regular Durbin Rocket run—and that’s a whole other part of the heritage and fun. “The Durbin Rocket is an actual West Virginia treasure, built new for the Moore-Keppel (lumber) company in Ellamore, West Virginia,” John says. The 1910 steam locomotive was built by Climax Manufacturing Company in Pennsylvania. “The lumber company ran it for many, many years and then it was taken out of state, and we found it and brought it back,” he says. “The Climax #3 is one of only three Climax steam engines left operating in the whole world.”

If the Castaway Caboose sounds good to you, don’t wait to make a reservation. “Just about everyone, when they get back to Durbin, makes reservations for the next year,” John says. “We just had some people down there for two weeks—and this was their fifth straight year.” That kind of enthusiasm means to John that guests ultimately find the electronic silence peaceful. “Everybody that goes down there, their biggest fear is about being unable to use their cell phones. By the time they come out they say, ‘I hate to turn this on again.’”

photographed by Carla Witt Ford

Leave a Reply